Dangerous Waters

How far will OFAC go in sanctioning Russia's shadow trade?

Recent OFAC sanctions have focused on a handful of Russian shadow tankers. That’s surprising, since Moscow’s shadow fleet was designed to legally circumvent the price cap, keeping it safe from sanctions.

But the Kremlin got careless with its costly fleet, putting up to half its vessels at risk of similar blocking orders. Moscow-friendly traders and others might also be at risk. To date, OFAC’s campaign has been restrained. But that could change.

Either way, Russia’s shadow trade is looking much riskier for all involved. Expect Moscow to pay a price in higher freight rates, deeper price discounts and more exposure to the price cap.

Executive summary

Since mid-October, OFAC has sanctioned eight oil tankers for price-cap violations. While the agency’s actions have sidelined these ships—at least for now—the enforcements have drawn some scepticism for their seemingly limited scope. But there’s more going on here than many realize, much of it unexpected.

OFAC’s blocking program looks focused not on the mainstream fleet, but on Russia’s growing shadow fleet, to which seven of the eight blocked ships belong. That’s surprising—and important—because shadow tankers were supposed to legally sidestep the price cap, making them “immune” to price-cap sanctions.

It now appears, however, that the Kremlin got careless while assembling its shadow fleet—and not just with these seven ships. A large number of Moscow’s shadow tankers could now be at risk of OFAC action. So, too, could those who trade their tainted cargoes. If OFAC keeps going after at-risk actors, the Russian oil trade will become even riskier business, pushing up transaction costs and squeezing Moscow’s all-important oil income.

Sanction rules prohibit EU/G7 entities from providing key marine transport services—like chartering and insurance—except when cargoes comply with the price cap. To legally circumvent these rules, the Kremlin has been assembling a fleet of tankers cleansed of all ties to EU/G7 marine service providers.

Along the way, however, Putin’s anti-sanction technocrats got careless in their sanctions hygiene and left some U.S.-based service relationships in place. The eight tankers blocked so far, for instance, are all flagged in countries that outsource their flag registry businesses to private U.S. companies. Under U.S. price-cap rules, flagging is one of the six restricted marine transport services. What’s more, the U.S. price-cap rules allow OFAC to pursue not only the providers of restricted services, but any entity anywhere that relies on restricted U.S. services when transporting Russian oil priced above the cap. That includes shadow tankers.

Significantly, Moscow’s flag-state problem isn’t limited to these seven ships. Over 100 of Moscow’s active shadow tankers fly flags whose registries are run by U.S. companies. That includes three quarters of Sovcomflot’s tanker fleet.

Using U.S.-based flagging services wasn’t the Kremlin’s only blunder. Some 30 or so shadow tankers apparently carried U.S.-issued spill liability insurance—another restricted service—while disregarding the price cap. Altogether, just over half Russia’s active shadow fleet may now be in violation of price-cap sanctions and at risk of OFAC enforcement action.

Altogether, just over half Russia’s active shadow fleet may now be in violation of price-cap sanctions and at risk of OFAC enforcement action.

Worse still for Moscow, these at-risk shadow ships may have acted as vectors of “contagion,” infecting other participants in the shadow trade. Anyone who dealt in these tainted cargoes might, potentially, have violated U.S. rules and could now be at risk of enforcement actions. That includes the commodity brokers who marketed those barrels and the importers who bought them. The handful of shadow tankers currently blocked may be just the tip of a problem that runs broad and deep.

Blocking orders can significantly limit the usefulness of a tanker. They can be even more crippling for a commodity trading house. How many at-risk tankers—or traders—will end up on OFAC’s sanctions list? It’s hard to say. Enforcement agencies must walk a fine line between combatting the shadow trade and spooking mainstream shippers still active in Russia. If too many of the latter quit Russia, export volumes will fall, putting upward pressure on prices. OFAC’s posture will likely evolve with circumstances.

Moscow will, of course, try to restore these sidelined vessels to service. Perhaps, in time, it will succeed. But marked by sanctions and blocked from any dollar-denominated transactions, they will be of more limited use.

One thing seems certain, however. With each entity added to OFAC’s list, the shadow trade becomes a riskier business for all involved. As that realization takes hold, shadow trade participants will demand more compensation for their risk. That means higher freight rates for shippers, richer commissions for traders and deeper discounts for importers. And all that comes out of Moscow’s pocket.

What’s more, as shadow tankers get blocked, Russian exporters becomes more reliant on mainstream tankers, and thus more exposed to price-cap limits. All the more reason to keep pushing for better price-cap compliance by mainstream vessels.

Finally, this episode is a salutary reminder that the Kremlin’s vaunted technocrats are, in fact, quite fallible. This episode will be added to a lengthening list of major unforced errors, like leaving sovereign funds exposed to freezing orders and unilaterally wrecking Gazprom’s $80 billion European export business.

* * *

Introduction: the suspended voyage of the NS Century doesn’t bode well for Moscow’s shadow trade.

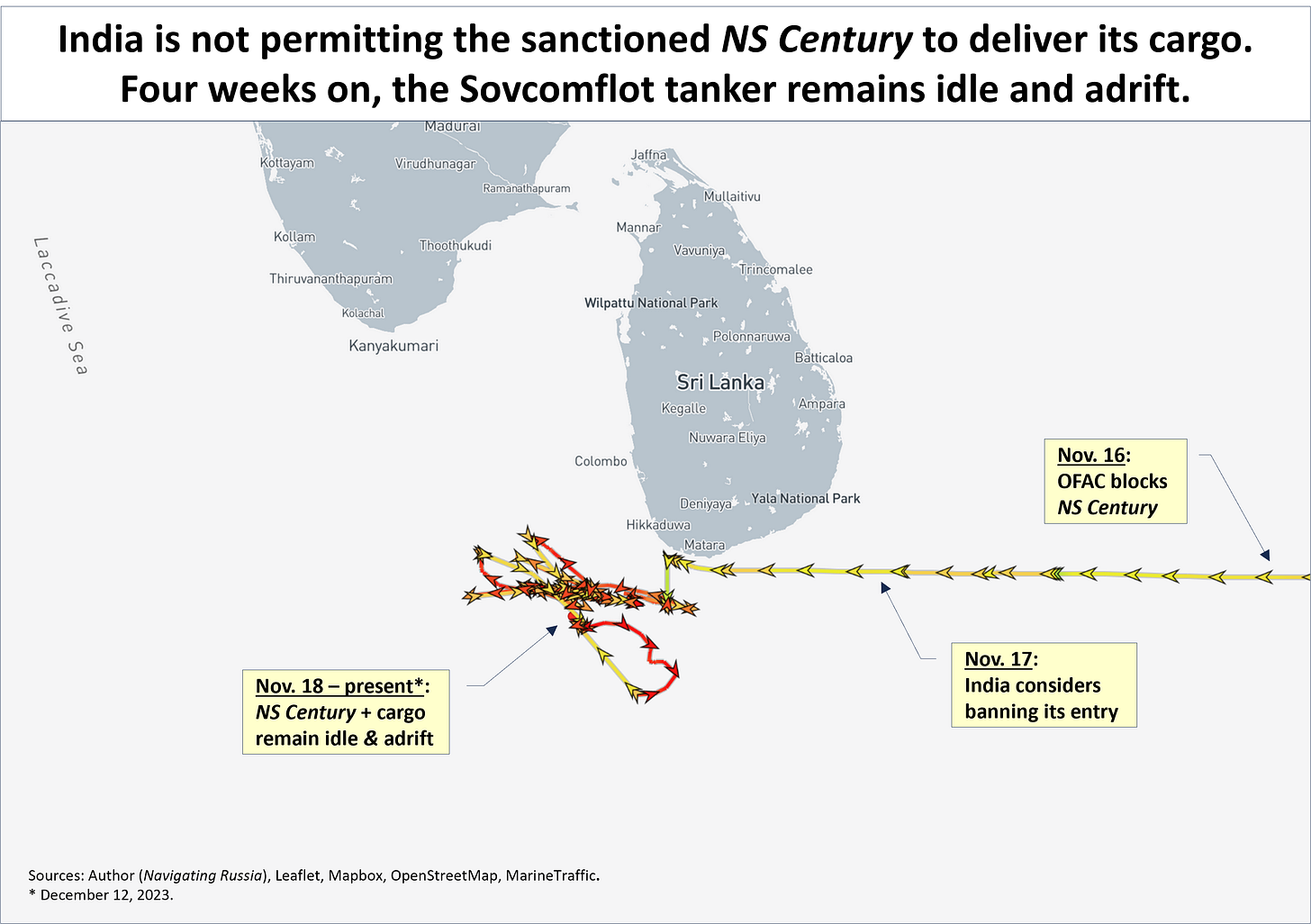

It should have been just another routine delivery of Russian oil to India. Instead, it turned into a stark reminder of the long reach of the U.S Treasury. On November 18th, the NS Century, an oil tanker belonging to Russia’s state-owned shipping company Sovcomflot (SCF), was nearing the end of its three-week voyage. The 17-year-old Aframax was just a few days away from delivering a cargo of Sakhalin crude, valued at an estimated $50 million, to the port of Vadinar. But just before 4 pm, as the vessel was rounding the southern coast of Sri Lanka, it suddenly deviated from its expected course. For the next two hours it steamed due south, away from India and deeper into the Laccadive Sea, before idling its engines and beginning to drift.

The cause of this unexpected course change had nothing to do with mechanical failure or navigational mishap. Rather, it was the result of actions taken two days prior in Washington. OFAC, the sanctions arm of the U.S. Treasury, announced it was “blocking” the NS Century and adding its owner of record—a Liberian shell company—to its formidable “Specially Designated Nationals” (“SDN”) list. In short, the NC Century had been sanctioned. That called into doubt not only the tanker’s ability to deliver its cargo to India, but to remain fully active the oil trade.

Blocking a tanker limits its usefulness in the heavily dollarized oil trade

Blocking a vessel prohibits it from involvement in any transactions using the U.S. financial system. So, it wouldn’t be possible, for example, to sell the NS Century’s cargo for dollars on arrival in India.

In the global seaborne oil trade, operating outside the dollar settlement system is challenging. The business is heavily dollarized. Oil prices are universally quoted in dollars. To efficiently run an export business on the scale of Russia’s—with daily sales in the hundreds of millions and buyers spread across 70 countries—requires currencies that are stable, convertible, widely available, liquid and easy to hedge. That’s not easy to do while avoiding the dollar, and other price-cap coalition currencies, like sterling and the Euro. That’s why the U.S. Treasury expressly permits a handful of Russian banks to settle energy trades in dollars. Otherwise, Russia might struggle to maintain export volumes, putting upward pressure on prices.

Moscow, of course, recognizes that dependency on dollar settlement creates a strategic vulnerability. The stranding of the NS Century is a tangible example. For months, the Kremlin has been pushing exporters to settle oil sales in alternative currencies. There’s been considerable success with sales to China. Sales to India have also shown progress, though here the going has not been easy.

Consider, for example, last summer’s currency row. India plays a critical role in sustaining the Russian oil trade. It’s the only available large-scale buyer for Russia’s flagship Urals grade crude. As such, Indian buyers enjoy significant bargaining power, which they have used to extract deep discounts on price.

In July, however, India reportedly pushed its advantage a step too far, when it insisted Russia accept payment for oil in rupees. The aim was to encourage Russia to invest more in India and import more Indian goods. Russian exporters flatly refused. The Russian Central Bank was unwilling to accept rupees because of their limited usefulness outside India.

Currencies like the UAE dirham have been more successfully used for the Russia trade. But the dirham doesn’t offer an entirely clean escape from the dollar system. Washington has reportedly been stepping up pressure of late on UAE banks to ensure compliance with the price cap when processing Russian oil transactions, apparently with some success. With the dirham pegged to the dollar, the UAE must maintain large dollar reserves and ready access to dollar clearance, which may make Emirati banks sensitive to pressure from US officials.

For the NS Century, the possibility of conducting trade outside the dollar system might help it return to service at some point. Time will tell. But its ineligibility for use in dollar-linked transactions puts limits on its usefulness.

A tanker in violation of sanction can also be “contagious”—potentially putting those buying and selling its cargo at risk of getting sanctioned.

But settlement isn’t the only challenge a tanker like the NS Century can pose. As we shall explore in more detail below, a buyer that purchases its current cargo—regardless of the settlement currency—it likely to be violating U.S. sanction rules, which could land it on the dreaded SDN list. In effect, NS Century is currently “contagious.” What’s more, it has likely been contagious to other counterparties for months, potentially putting all the traders and buyers dealing in its recent cargoes at risk.

So, it came as little surprise when, on November 17th—the day after the NS Century was sanctioned—Indian officials raised the alarm. According to reports, India’s shipping ministry had misgivings about allowing the tanker to berth at Vadinar. Given the legal and political complexities involved, however, it prudently passed the decision over to the foreign ministry.

No favorable resolution was quickly forthcoming. Lacking clearance to dock in India, the NS Century stopped making way on November 18th and enter its holding pattern. At this writing, nearly a month on, the situation remains unresolved. The blocked tanker—along with its valuable cargo—remains idle and adrift in the Laccadive Sea.

* * *

While assembling its shadow fleet, the Kremlin got careless with its sanctions hygiene and failed to take certain simple preventative measures…

The NS Century is not alone in having been effectively sidelined by OFAC. It is but one of eight such vessels blocked since mid-October. All the others were in ballast when sanctioned. Since, none has lifted any new loads. Most are now idle at anchor, scattered across the maritime periphery of Eurasia. Some have found refuge in Russian ports—Murmansk and Ust Lugansk. Others are idle off the coasts of Algiers, Malta, China and, of course, Sri Lanka.

Notably, six of these sanctioned vessels belong to Sovcomflot. The seventh is an anonymously owned shadow tanker.1 The eighth is a Turkish owned vessel carrying IG insurance, which marks it as a member of the mainstream fleet.

What’s somewhat surprising is that the SCF and shadow tankers were thought to have been effectively immunized from price-cap enforcement actions. They had supposedly severed the kinds of ties with EU/G7 marine transport services that could trigger a sanctions violation if they transported oil priced above the cap. But something seems to have gone wrong. It appears Kremlin officials got careless with their sanctions hygiene and allowed these vessels to continue using restricted Western marine services. Which is how these blocked tankers ended up in OFAC’s crosshairs.

U.S. price-cap sanctions target any entity—U.S. or otherwise—involved with cargoes priced above the cap while relying on restricted U.S.-based marine transportation services

To understand how these ships got sanctioned and whether more might be at risk, we need to look at the special way the U.S. has structured its version of the price-cap rules. A year ago, the price-cap coalition countries (“the coalition”) banned their nationals from providing maritime shipping services for the Russian oil trade. These services include things like shipping, trading and insurance (“covered services”). An exception is made, however, if the oil involved is sold at or below a capped price set by coalition policymakers.

For most coalition countries, price-cap enforcement focuses on domestic businesses and individuals. The price cap rules developed in the U.S., however, go a step further. They allows OFAC to sanction violators regardless of where they are based: “any person who evades” the price cap while relying “on U.S. service providers who provide covered services…may be a target for OFAC enforcement action” (emphasis mine).

The Kremlin’s shadow-fleet strategy: assemble a fleet scrubbed of any ties to restricted coalition marine services and, thus, able to carry cargoes priced above the cap without violating sanctions

So, if Moscow wanted to be able to sell oil above the price cap while not falling afoul of U.S. price-cap sanctions, it would need to develop a parallel shipping eco-system untainted by reliance on any covered shipping services provided by coalition entities—especially those based in the U.S. Trading, finance, chartering, insurance, etc.— shadow tankers would need to be scrubbed of any such services provided by coalition-based companies. And, once those ties were cut, alternative arrangements would need to be put in place.

That would be no easy task. Coalition entities play an outsized role in many of the world’s core shipping services. Some 95% of the global tanker fleet relies on coalition-based companies for one or more covered service. Historically, Russia has been heavily reliant on Western shipping services. Given the immense scale of Russia’s shipping needs, arranging alternative providers of these services —especially tanker chartering and insurance—would be all the more challenging.

But that is exactly what Moscow set out to do, starting in summer 2022. The central thrust of this project has been to assemble a stand-alone, “sanction-proof” fleet of tankers that is large enough to manage all Russia’s export needs, while being neither owned, insured or otherwise reliant on coalition service providers (see Measuring the Shadows). That would allow these to carry cargoes priced above the price cap without violating sanctions.

This supposedly sanction-proof fleet is made up of tankers from Russia’s state-owned fleet, Sovcomflot…

The core of this fleet is made up of the roughly 80 tankers belonging to Russia’s state-owned shipper, Sovcomflot. SCF’s estrangement from coalition service providers happened early, abruptly, and not of its own initiative. Shortly after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the EU sanctioned SCF, with far-reaching consequences. The Europe-based International Group of P&I Clubs (the “IG”)—provider of compulsory spill insurance to nearly all the world’s tankers—cancelled SCF’s coverage. To keep the fleet in service, the Russian Central Bank, through its re-insurance subsidiary, stepped in with an insurance guarantee. Next, European banks called in large loans, forcing SCF to liquidate part of its fleet. Still other Western service providers followed suit. By late summer of 2022, SCF had been thoroughly stripped of commercial ties to coalition-based covered services—or so it seemed.

Because SCF covers only some 15% of Russia’s shipping needs, Moscow has sought to augment it by assembling a fleet of anonymously owned shadow tankers. Across the global tanker markets, unidentified investors—many likely bankrolled by Russian loans—began aggressively buying vintage tankers from the mainstream fleet and putting them to work in Russia’s shadow trade. As with SCF, service ties with coalition-based providers were cut. Ownership, insurance and flagging were all routinely changed.

…along with vintage tankers recently purchased from the mainstream fleet for redeployment in the shadow trade

Separately, Russian exporters began aggressively shifting their business away from large, western commodity traders in favor of a new crop of smaller, lesser-known groups based mostly in the Gulf and the Far East. Some are directly affiliated with certain Russian exporters, others appear to enjoy very cozy relations.

Progress towards standalone fleet has been slow, but steady. By late summer of 2023, Moscow had assembled more than 250 tankers—shadow and SCF combined—supposedly “immune” from price-cap sanctions. That’s enough tonnage to manage just over half the country’s crude and product volumes at full export capacity, provided shadow vessels are allocated shorter, more efficient routes. Russia’s remaining export volumes, however, continue to be shipped by tankers chartered from the mainstream fleet, and, thus, subject to price-cap restrictions.

But for some tankers, the shadow-fleet task force somehow neglected to sever ties to restricted U.S.-based services.

When OFAC announced its first sanction of a SCF vessel on October 12, citing “the use of U.S.-based service providers” while transporting oil priced above the cap, the effectiveness of Moscow’s “immunization” strategy was called into question. When five more SCF vessels and one shadow ship got sanctioned for the same infractions over the course of November and early December, it was clear something had gone wrong with Moscow’s efforts to sever ties to covered service providers. Somewhere along the line, the Moscow’s technocrats had gotten careless.

Which services were they? And how many shadow tankers does this affect?

The pressing question now becomes: how widespread is the problem? To answer that question, we need to identify the “U.S.-based” service relationships have triggered the OFAC enforcement. OFAC has provided no specifics, but an educated guess is possible.

The lists of covered services put out by the EU, UK and U.S. vary somewhat, but none is long. The U.S. list notes six prohibited marine transportation services:

1. trading/commodities brokering,

2. financing,

3. shipping,

4. insurance,

5. flagging, and

6. customs brokering.

Of the first four, none appears likely to have gotten these vessels sanctioned. U.S. traders have largely pulled back from Russia. As noted above, exports are now dominated by niche players based outside of coalition countries.

U.S. lenders will be on a very tight leash by their compliance departments when it comes to Russia. They would be very unlikely to provide any trade or acquisition financing involving Russian oil or shipping. When it comes to basic settlement services, however, there is an explicit allowance for the Russian oil trade—so long as the entities involved are not sanctioned.

As for ship ownership, a U.S. connection looks unlikely, too. Shadow vessels tend to be owned by single-asset special purpose vehicles registered in offshore tax havens outside of coalition countries. So, ownership is unlikely to be the issue.

Insurance is straightforward: none of the sanctioned ships carries spill liability coverage from the American Club, the only U.S. based P&I club. Hull and machinery insurance data is harder to come by. But such insurance is also rather easier to secure from non-coalition providers. So, insurance looks unlikely.

That reduces our list to flagging and customs brokering. On the latter, it seems improbable anyone would hire an American customs broking company to clear Russian oil cargoes arriving in markets like India and China. So, we can probably set that aside as “unlikely.”

All tankers sanctioned so far have continued to use U.S.-based flagging services, which may be what put them in violation of price-cap rules and at risk of being sanctioned.

That leaves flagging.2 At first glance this, too, appears to be a non-starter. None of these tankers is U.S. flagged. But on closer inspection, a curious pattern emerges. Seven of the eight tankers—including all six SCF ships—are Liberian flagged. The eighth blocked tanker is flagged in the Marshall Islands.

These flag registries provide numerous critical services a tanker needs to operate internationally. These include certifying a tanker’s compliance with a range of statutory regulations concerning things like spill liability, structure integrity, pollution prevention, crew welfare, etc. Registries also maintain records relating to ship particulars, such as ownership and encumbrance.

Running a ship’s registry involves an immense amount of paperwork and due diligence, much of it technical in nature. Many states offering flags of convenience outsource the administration of their registries to private companies based elsewhere. Gabon’s ship registry, for example, is administered by a company based in the UAE. Gabon has become a flag of choice for many vintage tankers that have recently converted to the Russian shadow trade.

According to their websites, both Liberia and the Marshall Islands also outsource their registry operations to private companies. In both cases, those companies are based in the U.S. state of Virginia. So, if you’re a tanker flagged in Liberia or the Marshall Islands, all your flagging services will be provided to you by U.S.-based companies. It’s quite likely, then, that it was reliance on U.S.-based flagging services that got these tankers sanctioned.3

The flag-state problem appears to be widespread. Some 40% of Moscow’s supposedly sanction-proof fleet has been flying flags administered by private U.S. companies based in Virginia.

If continuing to use U.S.-based flagging services is the problem, how widespread is it among the active shadow fleet? Very widespread. Shadow fleet flagging is concentrated in just a handful of states. The top seven account for over 95% of the fleet.

Of those seven, the single most popular flag is… Liberia. Some 88 shadow fleet tankers—including 55 from Sovcomflot—fly the Liberian flag. Another 23 are registered in the Marshall Islands, making a total of 111 shadow tankers that are using U.S. flagging administrators. In effect, that means nearly 40% of the fleet Moscow has painstakingly assembled—at huge expense—to circumvent the price cap, may now, instead, have inadvertently violated those very price-cap rules, putting all those tankers at risk of OFAC enforcement actions. For Moscow, those flags of convenience may turn out to be anything but.

What’s worse for Moscow, there may be another problematic category of covered services apart from flagging: spill liability (“P&I”) insurance. The International Group of P&I Clubs includes a U.S.-based member called the “American Club.” As noted above, none of the currently blocked tankers has recently insured with the American Club. But a significant number of other shadow tankers have.

In April, it was reported that the American Club cancelled P&I coverage for a group 34 tankers because of price-cap violations. Within a few weeks, the St. Kitts & Nevis ship registry—administered out of the U.K.—deflagged roughly the same group of tankers. Relying on a U.S.-based P&I insurance provider while violating the price cap would likely put these tankers at risk of enforcement actions.

If shadow tankers relying on U.S.-based P&I insurance are added in, the number of vessels now in violation of sanctions could be upwards of 145 vessels—or well over 50% of the active shadow fleet.

That would bring the total number of shadow tankers at risk or already sanctioned to 145. That’s well over 50% of the total number of tankers currently engaged in Russia’s shadow trade.4 This figure includes some 75% of the entire Sovcomflot tanker fleet.

These are staggering figures. And they mark what can only be described as a massive blunder on the part of Moscow’s anti-sanction technocrats. What makes the error even more egregious is that it could have been so easily avoided. Moscow had ample time in the run-up to sanctions to reflag its SCF tankers to a low-risk flag state. SCF would have had extensive, regular exposure to its U.S. based flag administrators. It boggles the mind that no one connected the dots.

And as vintage vessels were being gradually purchased from the mainstream fleet for redeployment in the shadow trade, they could have easily swapped U.S.-linked flags for less problematic ones at the time of purchase. That’s standard procedure for conversions into the shadow fleet. Someone was asleep at the switch.

The same is true for compulsory P&I insurance. As newly purchased vessels get repurposed for the shadow trade, their IG insurance is routinely dropped, replaced by opaque arrangements of questionable adequacy. Most of the tankers expelled from the American Club last April had only recently been acquired for the Russian shadow trade. It’s hard to find any sound reason why their new owners didn’t drop IG coverage at the time of sale—like everyone else does. Again, it just looks like a careless—and potentially costly—error.5

These at-risk tankers may have acted as vectors of “contagion,” potentially putting those who traded and imported their tainted cargoes in violation of sanctions as well.

Moscow’s tanker blunder has a range of ramifications—all harmful to its interests. By giving OFAC a legitimate basis for deploying its potent SDN list, the Kremlin has worsened the overall risk environment around the Russian oil trade. More specifically, it has shown that many tankers thought immune to sanctions are now at risk of enforcement.

What’s more, for months, these vessels may have been acting as vectors of “contagion,” potentially putting other market participants at risk. OFAC’s price-cap guidance says, any market participants that “make purchases of Russian oil or Russian petroleum products above the price cap and that knowingly rely on U.S. service providers who provide covered services…will have potentially violated [price-cap sanctions]…and may be a target for an OFAC enforcement action.”

We’ll leave it to the lawyers to opine on whether traders and importers “knew” the tankers in their trades were “rely[ing] on U.S. service providers.” Some will surely argue that since those services were provided to the shipowners, their trading and importing clients “weren’t aware” there was a problem and, thus, they did not “knowingly rely” on U.S. covered services. That argument might get some traction on transactions completed prior to OFAC’s first sanctions announcement on October 12. Perhaps.

But for any transactions after October 12th, the market was on notice that at least some shadow tankers had sanctionable U.S.-servicing issues. Thereafter, if traders and importers didn’t know the vessels carrying their cargoes were contagious, they should have. A warning had been issued. It was incumbent on them to do their due diligence.

As markets come to recognize how widespread the contagion may be within the shadow trade, levels of perceived risk will likely rise. That could push up transaction costs, widen spreads to benchmark prices, and hit Moscow’s bottom line.

Regardless of which way the contagion call goes, what’s clear is that levels of perceived risk around Russia’s shadow trade will go up. Suppliers of shadow trade services and importers of oil priced above the cap will demand compensation for the additional risk they now face.

These risks are spread across the supply chain:

higher carrying risk—reducing shipowner appetite and pushing up freight rates

Shadow tanker owners may hike their rates for cargoes priced above the cap. Rising risk may also cause mainstream tankers to raise rates for Russian cargoes. Mainstream ship owners are already feeling the chill of stepped-up scrutiny from sanction enforcement agencies. Three of the largest Greek fleets are reported to have pulled out of Russia in recent weeks over risk. Tighter supply from the mainstream fleet can only push Russian rates higher.

Higher handling risk—causing traders to demand higher compensation

The coterie of friendly commodity traders managing Russian exports may also demand more compensation for the additional risks they now face. As noted above, many may already be in violation of U.S. sanction rules. As sophisticated charterers of commercial vessels, arguments that they didn’t “knowingly rely” on U.S. covered services may be hard to sustain.

And if dealings with contagious shadow tankers haven’t put them at risk, then providing false price attestations to mainstream shippers may have. The U.S. price-cap rules say providing “false information, documentation, or attestations” to U.S. providers of covered services “will have potentially violated the [price cap]… and may be a target for an OFAC enforcement action.” So, if they’ve ever provided a false attestation to a mainstream tanker insured by the American Club, financed by a U.S. bank, owned by any U.S. investors or flagged by a state outsourcing its registry operations to a U.S. company, that trader may already be at risk.

Commodities traders may be particularly sensitive to sanctions risk. Getting blocked from dollar settlement systems is a crippling blow for any trader handling large-scale, long-haul oil trades.

Higher performance risk—causing importers to see Russia as a less reliable supplier

Importers, too, will see a range of higher risks around Russian oil. To start with, performance risk has gone up. If you contract for a Russian cargo, how certain can you be that it will arrive? Look at the NS Century. Savvy Indian and Chinese traders will likely use deteriorating performance risk as a hammer to beat down Russian prices.

Higher “contagion” risk—causing exposed importers to demand deeper discounts to compensate for stepped-up risks.

As with traders, some importers might already be in violation of U.S. sanctions for buying oil transported by a contagious tanker. In future price negotiations, these importers could argue “Russian oil is full of hidden risk.” As compensation, they could demand yet deeper discounts on price relative to market benchmarks.

In the end, all these higher transaction costs and deeper discounts amount to the same thing: a squeeze on oil revenues flowing back to Moscow.

Idled shadow tankers will force Russian exporters to rely more heavily on the mainstream fleet, exposing more of their revenues to price-cap limits.

OFAC sanctions can squeeze Russian oil income in on other important way: by reducing the availability of shadow tanker capacity. It’s been two months since first group of tankers was sanctioned. They all remain out of service, and there’s no certainty when—or if—they’ll resume transporting Russian oil. In the meantime, the reduction in available shadow vessels will force Russian exporters to rely more heavily on the mainstream fleet. That, in turn, means greater exposure to the price cap. The more tankers OFAC sanctions—the greater the exposure.

But for price-cap exposure to really make a difference, compliance more robust and caps set at lower levels. Recent analysis suggests effective compliance by mainstream tankers has been poor. Russian exporters appear to be using mainstream vessel to ship cargoes priced above the cap. The likely explanation: fraudulent price attestation. Traders chartering mainstream tankers are underreporting prices to secure use of their vessels without making genuine reductions in pricing.

To improve the integrity of price attestations, policymakers should require that only coalition-based traders are allowed to issue price attestations to mainstream vessels.

One way to reduce false attestations is to make certain that traders providing them are subject to audit and legal action by coalition states. In other words, make sure the traders providing pricing information to ship owners have deep business ties in coalition countries. This creates higher levels of accountability.

Many coalition-based traders were previously active in Russia, and some might be prepared to re-engage. Moscow, of course, would now prefer to keep them out—fraudulent attestations have become a core evasion technique. But if policymakers start requiring attestations to be issued by coalition-based traders, Russian exporters will have to sell through them if they want access to mainstream tankers.

Sidelined shadow vessels may also struggle to service the Kremlin-subsidized loans likely used to acquire many of them

The idling of shadow tankers has second order costs, too. Many vessels have recently been acquired second-hand at record-high prices, with aggregate acquisition costs on the order of five billion dollars. Much of this has likely been bankrolled by Russian banks, which are now offering cut-rate loans—deeply subsidized by the government—for ship acquisition. Sidelined vessels, however, aren’t able to generate income. If the list of blocked tankers grows, we could see a string of loan restructurings and defaults.

How fast and how far might OFAC go? It’s hard to say.

The consequences of Moscow’s tanker blunder—higher transaction costs, deeper discounts, and greater exposure to the price cap—are all bad news for the Kremlin. But how bad might it get? Much depends on how far OFAC plans to go with its blocking campaign. That’s hard to tell—OFAC doesn’t tip its hand.

There is, however, one intriguing data point that may or may not indicate the potential scope of OFAC’s plans. In mid-November, it was reported that OFAC sent letters to ship managers across a number of countries requesting information on some 100 vessels suspected of violating sanctions. It’s not clear from media accounts whether those letters went to managers of shadow tankers or mainstream tankers or a combination of both. If the letters mostly concerned shadow tankers, then the number of ships targeted is broadly in line with number of shadow tankers using U.S.-based flagging services—111. That would suggest OFAC’s list of potential targets is aggressively long.

OFAC will likely try to walk a fine line: ratcheting up the pressure on Moscow, but without spooking the mainstream shipping markets

Even if OFAC does have a long target list, it may continue to proceed with restraint—at least for now. Rising risk, as we’ve seen, can hit Moscow’s bottom line. But if it rises too far too fast, it could spook the mainstream shipping markets. Russia trade could then suffer from a shipping capacity shortage, constraining export volumes and pushing up energy prices. Ultimately, the speed and scope of OFAC’s campaign will be shaped by evolving market sentiment.

Expect Moscow to be hard at work trying to return blocked vessels to service…

And then, of course, there’s the question of Moscow’s response to sanctions. Kremlin troubleshooters will now be hard at work, looking for ways to return these idled assets to service. Potential solutions run the gamut. SCF management has said they will petition for removal from the SDN list. That, however, could take some time.

In the interim, expect a mass reflagging of vessels flying problematic colors. Many flag states may refuse to take them on. Several have already reportedly come under increased pressure to be more robust in requiring shadow ships on their registries to comply with international shipping regulations. But some flag of conveniences somewhere is likely to embrace such a windfall business opportunity.

…though they will likely face significant limitations.

If these tankers do find a flag state that will take them and are returned to service, they will be operating with significant limitations. Questions around compliance with international safety requirements will only grow. So too will the environmental threat these vessels pose. All this will only strengthen the case for demanding verification of adequate spill liability insurance before granting innocent passage through European waters.

Some ports may be reluctant to allow entry to blocked tankers—even once they’re reflagged. Expect Moscow to also mount an aggressive push to restore port entry rights in key markets like India and China. It will be interesting to see if those countries relent. They cannot be happy that Moscow’s poor sanctions hygiene has put their own importers at risk of sanctions. If they think receiving a blocked tanker might invite OFAC to sanction one of their at-risk companies, they may discretely advise Moscow to dispatch those vessels elsewhere.

If the list of block tankers expands significantly, some of Moscow’s schemers might explore more aggressive solutions. They could, for example, fabricate entirely new identities, replete with false IMO numbers, flag registrations and other essential certifications. It’s been done before. They might even steal a page from the great Ukrainian writer, Nikolai Gogol, and try to swap identities with similar vessels slated for the shipbreaking yards.

But impostor tankers with fraudulent paperwork would be hard to use where Russia’s need is greatest: in the heavily monitored waterways of Europe, through which 80% of Russia’s export oil flows. The risk of detection and detention is just too high. Instead, such dubiously documented ships would probably end operating mostly on the high seas, shuttling cargoes between major lightering zones.

* * *

Measures coalition members can take to keep the pressure on Moscow

There is a range of measures that policymakers and enforcement officials can take to keep the pressure on Moscow. These include:

OFAC can continue adding tankers to the SDN list as quickly as practical;

OFAC might also add one of the new coterie of Moscow-friendly commodity traders to the list—perhaps starting with a smaller player, to minimize disruptions to flows.

OFAC might also speak with major importers, such as China and India, to help them understand the risks their importers run by continuing to receive cargoes priced above the cap and carried by blocked or at-risk tankers.

Coalition policymakers could improve price-cap compliance by allowing price attestations to be issued only by traders based in coalition countries.

Coalition policymakers can pressure flag states hosting at-risk shadow tankers to deflag them—especially tankers already sanctioned. For those not at risk, they should more robustly enforce international regulatory requirements, such as adequacy of spill insurance. States offering to flag sanctioned vessels should be pressured not to.

European policymakers could safeguard the environment and pare back the shadow fleet by introducing an on-line spill insurance verification requirement, initially for the Baltic, that requires compliance with existing international conventions and IMO guidelines as a precondition for innocent passage through European waters.

The Kremlin’s blundering technocrats

Finally, at this moment in time, when the Kremlin is trying its hardest to strike a pose of invincibility, it’s useful to recall how capable its technocrats are of massive blunders. The sanctioned tankers debacle will be added to a growing list of major unforced errors, like leaving sovereign funds exposed to freezing orders, unilaterally wrecking Gazprom’s $80 billion European export business and cynically believing Europe would never have the spine and moral conviction to impose oil sanctions.

Disclaimer: No Advice

The author of this substack does not provide tax, legal, investment or accounting advice. This report has been prepared for general informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for tax, legal, investment or accounting advice. The author shall not be held liable for any damages arising from information contained in the report.

Endnotes

Strictly speaking, the state-owned SCF is distinctive in certain ways from the anonymously owned Russian shadow fleet but is often lumped together with it. See Chapter 2 of Measuring the Shadows.

“Flagging” is central to the international maritime legal order. It refers to registering a vessel with the country whose laws it is subject to. Historically, ships were flagged in countries to which they had strong ties. For example, it’s where their owner is domiciled. But many countries now offer “flags of convenience.” For a fee, these flag states will register ships with no inherent ties to the country. Among other things, flag states are responsible for making sure the ships on their registry comply with international regulations and requirements, like passing statutory safety surveys and carrying adequate spill insurance. Some flag states, however, have become notoriously lax in the enforcement of these requirements. Their vessels are often poorly maintained, underinsured and pose a menace to coastal communities everywhere.

See Tradewinds, 17 November 2023 and Tradewinds, 21 November 2023.

Here, shadow tankers “currently engaged” in Russia refers to non-IG-insured tankers—including SCF vessels—that have lifted oil from Russia at least once in the twelve weeks leading up to October 15, 2023.

On the life-cycle of the shadow fleet, see Chapter four of Measuring the Shadows.

Excellent article, as usual.

You must think Russians are retarded. I disagree. "Russians don't take a shit without a plan" - Hunt for Red October

Russia left it's reserves out there hoping West would sanction them. West have not even appropriated them yet and are already terrified everyone wants out of USD and Euro - and besides Russia has 4 trillion in Western assets they can take inside Russia if it's tit for tat. . Even so - China is pulling hundreds of billions out in UST. Total self own. Boats/oil same deal Russia does not want Russia to be European citizens enemy by cutting off oil. Russians wants Western politicians to be Europeans enemy by doing it for them. Russia needs no dollars or Euros what are they going to do with them? There is sanctions on Western services/goods in case you have not heard. Hopefully Europe cuts these illegal ships off 100% and In 3-4 years All Western politicians will be replaced with more Pro Russian ones as they slide into poverty.

Russia does not need West at all. It doesnt even need China really it's an autarky unlike China but China provides everything West used to at a much cheaper price. 6 axis CNC lathes to make more ammo to Autos. West does need Russian resources, more than ever now that Africa is finally getting free of European yoke. This inescapable fact will always cause Western sanction to fail.