Measuring the Shadows

Moscow’s Strategies for Evading Oil Sanctions and How to Stop them from Succeeding

August 2023

This analytical report assesses on-going Russian efforts to circumvent the price cap and recommends high-impact measures for implementing oil sanctions more effectively.

Oil sanctions have been taking a toll on Russia, but Moscow has been hard at work on strategies for circumventing them. With Russian oil now trading above the price cap, the effectiveness of those strategies is being put to the test. Western policymakers have the sanction tools needed to thwart Moscow’s evasion efforts and further erode Russia’s economic resilience. But only if specific measures are taken to improve how those tools are used. If measures aren’t taken, sanctions could be at risk of unraveling.

Abstract

After some early success, oil sanctions are now being put to the test as Urals rises above the $60 price cap.

In recent months, oil sanctions have been taking a toll on Moscow’s revenues. The EU/G7 embargo has profoundly disrupted markets for Russian oil, forcing exporters to offer unprecedented discounts to secure large-scale demand. But prices have firmed up over the summer. And with Urals now quoted above $60, the effectiveness of the price cap is being put to the test.

Moscow has been hard at work on developing circumvention strategies. Its shadow-fleet strategy has made progress, but faces significant challenges.

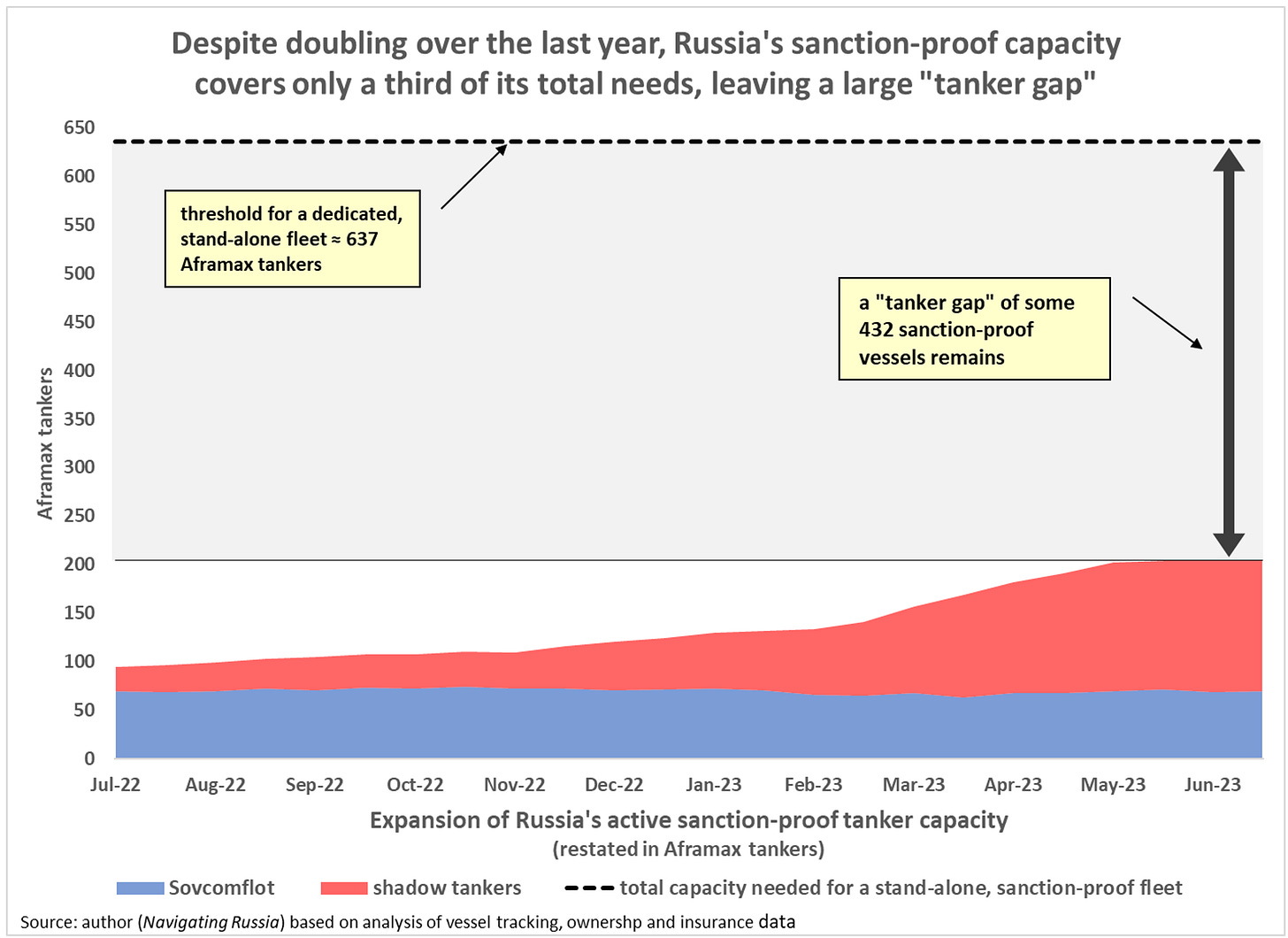

For months, Moscow has been developing strategies aimed at circumventing the price cap. Chief among these is an effort to assemble a fleet of shadow tankers able to transport oil with impunity, regardless of price, and large enough to keep Russia’s export volumes whole. The fleet has expanded substantially, but Moscow’s shipping needs are immense; the fleet currently at Moscow’s disposal has reached only a third of the capacity that Russia requires for full export autonomy. Gathering a shadow fleet big enough to keep exports whole will likely be very expensive and take years to amass.

A complementary strategy of price attestation fraud, however, has the potential to substantially subvert the sanctions regime.

In parallel, Moscow has also been developing a complementary strategy of price attestation fraud. It seeks to use mainstream, sanction-compliant tankers to transport oil priced above the cap by exploiting known vulnerabilities in the sanction compliance regime. Policymakers are aware of this strategy, and have taken preliminary steps to counter it, though it’s not clear whether these measures will be adequate. If left unchecked, pricing fraud could substantially subvert the sanctions regime.

The high-stakes option of oil weaponization has now become a remote risk.

Moscow’s push to develop these circumvention strategies followed its decision last winter to quietly back away from earlier threats to weaponize oil exports by withholding volumes and engineering a supply crisis. For Moscow, weaponization was a high-risk option that amounted to playing dice with its all-important oil revenues. The resulting price surge could have proved short lived, leaving support for Ukraine undiminished and Moscow in a far weaker position, with revenues down, OPEC relations strained and shut-in production capacity steadily decaying. Moreover, as Moscow approached its decision point late last year, its broader risk environment was rapidly deteriorating, with its gas weaponization strategy faltering, energy prices tumbling, and military setbacks mounting. Customary Kremlin conservatism kicked in, dampening Moscow’s appetite for a high-stakes gamble. And that appetite looks unlikely to return anytime soon.

Policymakers possess the sanction tools needed to counter Moscow’s evasion efforts but must take specific steps to improve how sanctions are implemented if they are to succeed.

EU/G7 policymakers now have the necessary sanction tools to counter Moscow’s circumvention strategies and further constrain Moscow’s access to critical windfall revenues. But to succeed, they must improve how current sanctions are being implemented. With finite enforcement resources, they should focus on high impact measures that will both intensify the economic impact on Moscow and safeguard sanctions from Moscow’s efforts to unravel them.

This report details four such measures:

ratcheting down price caps, which could actually reduce inflationary pressure;

reducing the risk of price attestation fraud by whitelisting traders allowed to charter price-cap compliant, mainstream tankers;

cracking down on the involvement of EU/G7 entities in the sale of used tankers to Russian or undisclosed buyers;

requiring ships transiting EU/G7 territorial waters to verify that their spill liability insurance is adequate and current, which can sharply reduce both shadow tanker activity and the risk of a catastrophic accident.

Oil sanctions are worth the extra effort to get right, because of the unique and indispensable role that periodic oil windfalls play in the political economy of the Putin regime. They renew regime vitality, strengthen cohesion of elites and restore appetite for risk. Oil sanctions, if assertively implemented, can dim Moscow’s hopes for future windfalls and increase risk aversion. In turn, heightened caution can hasten the day Moscow recognizes a retreat from Ukraine has become its best option.

Table of Contents

A note on terms and data.

Measuring the Shadows: Introduction

Part 1: Moscow’s “physical” evasion strategy: assembling a sanction-proof fleet

Chapter 1: Russia’s peculiar shadow fleet—evading sanctions through immunity, not subterfuge

Chapter 2: Measuring the Shadows—how big is the sanction-proof fleet in Russia?

Chapter 3: How many shadow tankers does Moscow need in all?

Chapter 4: Can Russia close its “tanker gap?”

Part 2: Moscow’s “paper” evasion strategy: engaging mainstream tankers using fraudulent pricing information

Part 3: Moscow’s strategy for boosting prices

Chapter 6: Moscow contrives to have OPEC solve its oil price problem

Part 4: Helping Moscow fail faster

Conclusion: No more oil windfalls—hastening Russia’s retreat from Ukraine

Appendix: A brush with disaster in the Danish Straits—shadow tankers menace the Baltic

Recommended resources on Russian oil sanctions

Acknowledgements

Endnotes

A note on terms and data

Throughout this report, the term “oil” refers to both crude and refined products together. So, “Russian oil export volumes” would mean the combined export volumes of Russian crude and refined product.

The terms “EU/G7” and “price-cap alliance” are shorthand for the alliance of countries participating in oil sanctions against Russia. In addition to EU and G7 member states, these include countries such as Norway, Australia, and South Korea.

Except where otherwise noted, the analysis in this report is based largely on shipping, ownership and insurance data that are current as of early July 2023.

Executive Summary

Late last year, Moscow abandoned the idea of weaponizing oil exports in response to the introduction of EU/G7 oil sanctions. It opted, instead, to develop strategies for circumventing the price cap. As Urals tops the $60 per barrel price cap, the robustness of EU/G7 oil sanctions will face their first major test in face of Moscow’s circumvention strategies.

The first of Moscow’s two circumvention strategies involves assembling a fleet of “sanction-proof” shadow tankers.

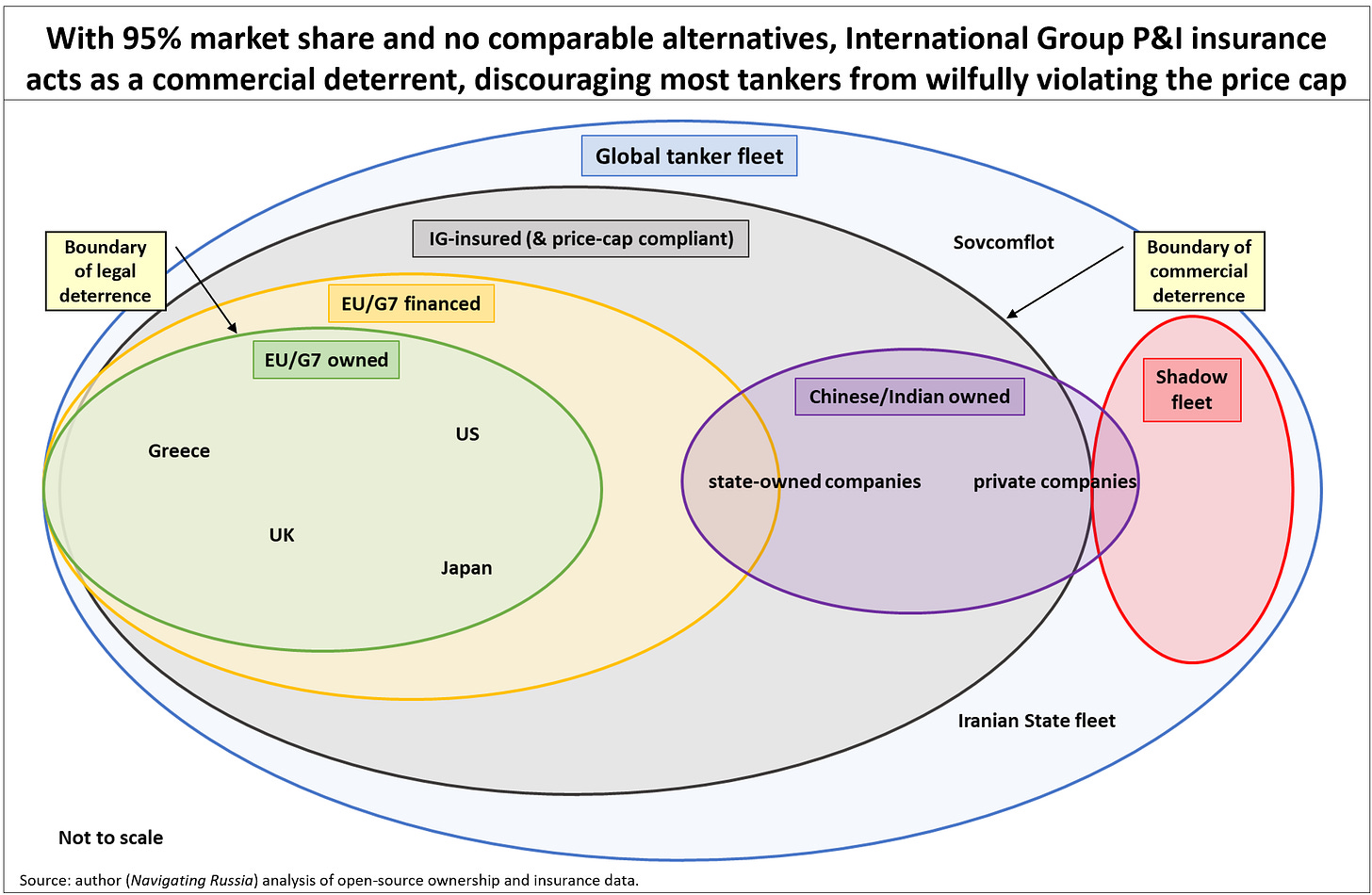

Moscow’s evasion efforts have centered around two complementary strategies. The first of these involves assembling a fleet of “sanction-proof” shadow tankers able to disregard the price cap openly and with impunity. To enjoy immunity from sanctions, however, these tankers need to be neither owned, financed nor insured by EU/G7 entities. Otherwise, they face significant legal or commercial consequences for violating the price cap. The pool of such sanction-proof tankers, however, is very limited. Some 95% of the global tanker fleet arrange their mandatory oil spill liability (“P&I”) insurance through the non-profit International Group of P&I Clubs (the “IG”), which is centered in Europe and requires covered vessels to observe Russia sanctions. Much vessel financing and many charterers require IG P&I policies since there is no comparable alternative in the market. Because of the broad global footprint of hard-to-replace EU/G7 marine insurance, however, some 95% of the global fleet faces significant legal and/or commercial consequence for violating sanctions. That leaves only a small pool of vessels suitable for the shadow-tanker business model (see Executive Summary Figure 1).

This fleet has grown substantially since last summer…

Since last summer, the cohort of shadow tankers active in Russia has grown substantially. Their capacity has increased by nearly 12 million deadweight tons, the equivalent of around 110 Aframax class tankers—the most widely used tanker class in the Russian trade (see Executive Summary Figure 2).

… primarily through purchases from the mainstream fleet, not recruitment from the global shadow fleet…

Moscow’s shadow fleet appears to be primarily “bought” not recruited. Few of these tankers come from the broader global shadow fleet. Only 11%, for example, appear to have been engaged in the Iran trade. Instead, some 82% of these tankers have changed hands since March 2022, with most having recently been aging tankers in global mainstream fleet. Once sold to new, anonymous owners, they were stripped of any ownership and insurance ties that could make them vulnerable to sanctions and put to work in the Russia trade.

…but so too have Russia’s shipping needs, as the EU/G7 embargo forces its oil to more distant markets.

At the same time Moscow’s shadow fleet has been expanding, so too has its need for tanker capacity. The EU/G7 import embargo has displaced over 70% of Russia’s seaborne exports, forcing most of it to be rerouted from destination ports in Europe to more distant, less familiar markets East of Suez (see Executive Summary Figure 3).

The net effect has been to roughly double the amount of tanker capacity Moscow needs just to maintain the same level of daily deliveries. Through June 2023, Moscow has maintained daily exports of oil (crude plus refined products) at six million barrels per day or above since February 2022. To sustainably keep exports whole going forward while completely circumventing the price cap, Moscow would need a standalone, sanction-proof fleet of some 68 million deadweight tons of capacity—equal to around 637 Aframax tankers (see Executive Summary Figure 4).

The sanction-proof fleet active in Russia covers only a third the size it needs to be to keep exports whole and free from price-cap constraints.

When the capacity of Moscow’s active shadow fleet is combined with that of Russia’s state-owned shipping company, Sovcomflot, it totals around 22 million deadweight tons, equal to some 205 Aframax tankers (see Executive Summary Figure 5). This is roughly double that of a year ago, but still comes to less than a third of Moscow’s need. The result is a “tanker gap” equal in size to some 432 Aframax tankers.

The resulting “tanker gap” will be hard to close.

The prospects for closing this large gap anytime soon are dim, owing to structural impediments. Despite significant efforts, Moscow only managed to reduce its tanker gap by some 20% from July 2022 to June 2023 (see Executive Summary Figure 6).

Used market prices have soared…

The aggressive buying activity in the cohort of 16-to-20-year-old tankers—which provides most of the tonnage for the shadow fleet—has caused record high valuations in the used tanker markets. Prices for 15-year-old Aframaxes have more than doubled owing to constrained supply (see Executive Summary Figure 7).

…and supply is constrained…

To substantially close the tanker gap would put immense additional upward pressure on used tanker prices. Even after the recent heavy buying in the market, Moscow’s sanction-proof fleet currently accounts for just 17% of the carrying capacity of all 16-to-20-year-old tankers worldwide in the relevant classes. To close the tanker gap, that figure would have to quadruple to 69% and require an accelerated acquisition campaign of unprecedented scale (see Executive Summary Figure 8).

…weakening the economic rationale of the program, which may help explain the recent slowdown in shadow fleet expansion.

At today’s valuations, that program would easily exceed $15 billion and already calls into question whether such a high upfront price tag is justified by future, risk-adjusted returns. But given the limited liquidity in the tanker markets, any effort to buy this many tankers on a compressed time scale would push the ultimate price tag far higher, further eroding the economic rationale behind Moscow’s tanker expansion program. More simply put, Moscow’s shadow tanker strategy has pushed used tanker prices so high that further expansion is getting hard to justify on economic grounds. That may help explain the sharp slowdown in shadow fleet expansion observed since May (see Executive Summary Figure 2 above).

* * *

Moscow’s second circumvention strategy seeks to fraudulently ship non-compliant cargoes on mainstream tankers by exploiting a known price-cap compliance vulnerability.

Moscow’s second strategy for circumventing sanctions seeks to secure capacity on mainstream tankers for cargo priced above the cap. This involves exploiting a known vulnerability in the price-cap compliance regime. Owners of mainstream tankers must obtain a “price attestation” from traders stating that the cargoes they are shipping comply with the price cap. Many of the traders now handling Russian exports are based outside EU/G7 jurisdictions and have close ties to Russian exporters. This means they face no sanction risk for dealing in oil priced above the cap. It also means if a Russian cargo can be sold above the price cap, but no shadow tanker is available to lift it, these traders have an incentive to fraudulently secure capacity from mainstream vessel by providing a price attestation that falsely claims the cargo is price-cap compliant.

Due diligence by ship owners is supposed to prevent this bad-actor scenario from occurring…

This scenario—bad actors committing price-attestation fraud—is a known vulnerability in the price-cap compliance regime and was flagged by policymakers in guidelines to market participants last fall (see Executive Summary Figure 9). To avert it, policymakers advised ship owners to perform due diligence when taking on customers and provided red flags to watch out for.

…but it doesn’t appear to have worked adequately on exports from Kozmino in the early months of sanctions…

On its own, this advice does not appear to have been sufficient to prevent price-attestation fraud. Russia’s ESPO grade crude, which ships primarily out of the Pacific port of Kozmino, has consistently been quoted above the price cap since December. Available data appear to show that traders shipped large volumes of oil priced above the price cap on mainstream tankers, quite likely by providing fraudulent price attestations. After this came to the attention of sanction enforcement officials, the U.S. Treasury issued a warning in April. Since then, the volume of Kozmino exports lifted by mainstream tankers has fallen below 10% (see Executive Summary Figure 10).

…and it’s not clear that adequate measures are yet in place to prevent price attestation fraud from recurring today as Urals surges above the price cap.

It is surprising that price-cap compliant tankers were lifting large volumes from Kozmino in the early months of sanctions, since so many of the traders active in the Kozmino trade would likely have triggered one or more due diligence red flags. And it’s not entirely clear what’s behind the more recent retreat of the mainstream fleet from Kozmino. Is the result of more exacting diligence standards by ship owners? Or is it a decision by traders and Moscow to deploy additional sanction-proof tankers to the lucrative Kozmino trade, most of which goes to nearby China and thus requires only a small number of dedicated tankers to maintain. This becomes a very relevant question as the Urals grade crude surpasses the price cap, since the Urals trade requires a far larger amount of tanker capacity to maintain (see Executive Summary Figure 11).

Moscow opted for the low-risk strategy of price-cap circumvention instead of the high-risk strategy of oil weaponization.

Moscow adopted these two, low-risk circumvention strategies in lieu of the high-risk strategy of oil weaponizing that it had been previously threatening. Weaponization would have involved engineering a global supply crisis by slashing export volumes. That, however, would have been an extremely high-risk strategy, gambling as it does with Russia’s all-important oil revenues. It had a significant chance of backfiring if the resulting price surge proved short lived and Ukraine’s supporters remained resolute in the face of market turmoil. Moscow would have then ended up in a weaker position, with export volumes sharply reduced, revenues down, market share lost, OPEC relations damaged and shut-in production capacity steadily deteriorating. Its decision to forego weaponization was likely influenced by the deteriorating risk environment of late last fall, as Moscow’s gas weaponization strategy faltered, energy prices tumbled, and military setbacks mounted.

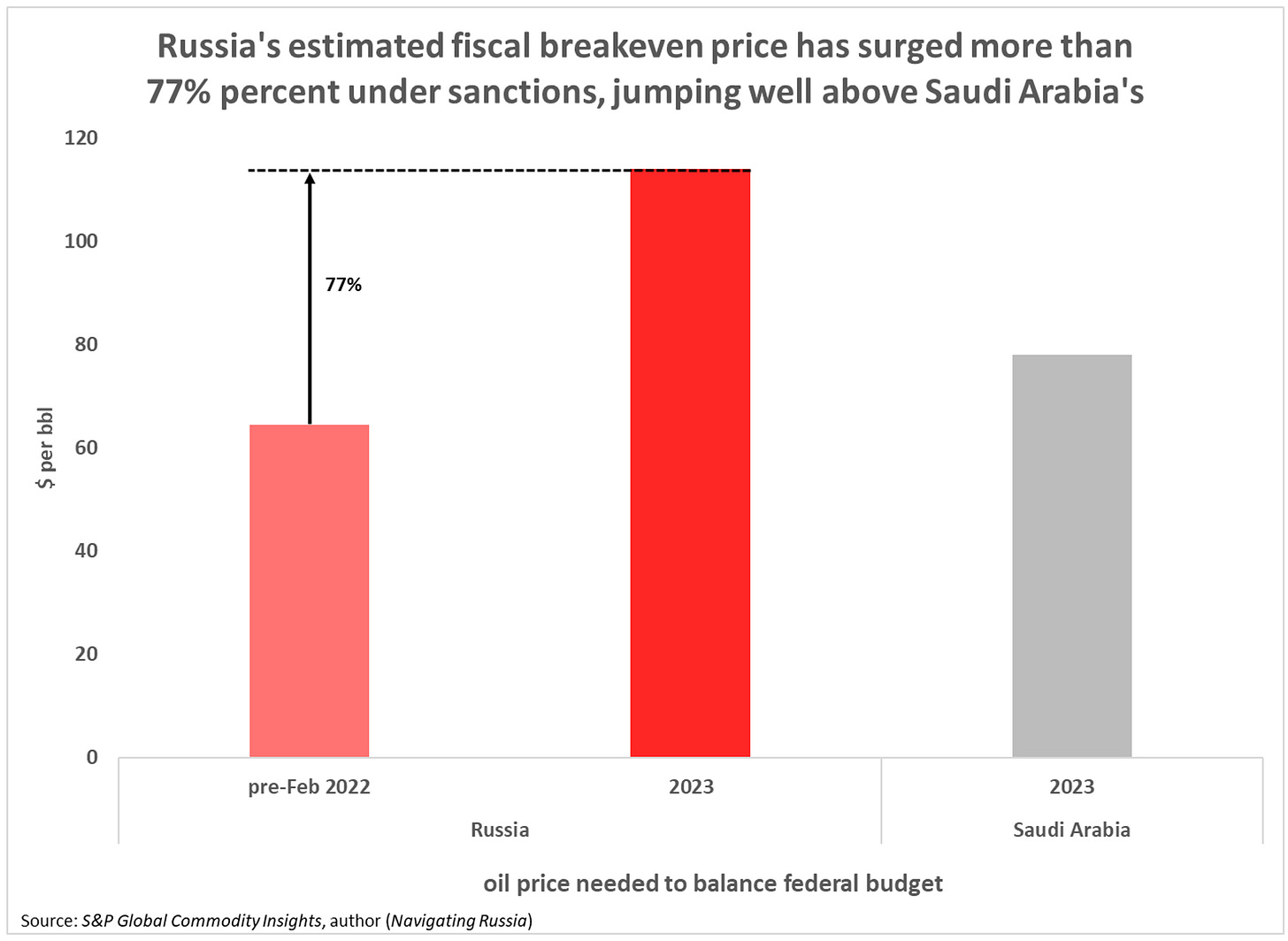

Nonetheless, the impact on Russia’s budget has been painful, with the 2023 budget plunging into deficit while its estimated fiscal breakeven oil price jumped by 77%.

Moscow’s circumvention strategy combined with the rising costs of its war on Ukraine have placed strains on the Russian budget. Budget revenues from oil were down 47% year-on-year in 1H 2023, despite Brent averaging only 25% lower, owing in part to a significant widening in the discount at which Urals trades to Brent. Historically, discounts had been in the $1 to $2 range, but under sanctions have routinely ranged from $20 to $30. The discount, in turn, has been driven by Moscow’s loss of pricing power, as India has emerged as the only reliable buyer in size for its diverted Urals flows and used its quasi-monopsonist leverage to extract painful discounts from Russian exporters. This collapse in oil revenues has helped push Russia’s 2023 budget into the red, with a ballooning deficit that by the end of April was already 17% ahead of full-year 2023 forecasts. Accumulated surpluses from 2022 are being consumed. The discount and war costs have also caused the estimated 2023 fiscal breakeven price to skyrocket to $114, up 77% over pre-February 2022 levels, and greatly exceeding that of the OPEC+ cartel’s other leading producer, Saudi Arabia (see Executive Summary Figure 12).

Moscow’s third anti-sanction strategy has been to contrive to have OPEC lift prices with cuts while avoiding any reduction in its own exports

In the face of the painful discount, Moscow could have unilaterally reduced Urals exports to regain some pricing power. But throughout the winter and spring, it remained highly reluctant to unilaterally cut output, and export levels remained at or above levels of January and February 2022 (see Executive Summary Figure 13). Instead, Moscow contrived to have its OPEC partners raise prices by cutting output, while avoiding any export cuts of own.

This radical shift in price sensitivities along with other consequences of Russia’s war on Ukraine appear to have strained relations between Moscow and OPEC.

This, however, proved a challenge. Moscow’s war on Ukraine has strained its relations with OPEC in many ways, and not just because of the radical realignment of oil price sensitivities. The deep discount at which Moscow has been selling Urals to India has depressed pricing more broadly for Gulf exporters in the Indian Basin. The doubling of Moscow’s tanker usage has pushed freight rates up for all exporters. By weaponizing of gas and grain, and threatening to do the same with oil, Moscow has roiled global energy and food markets, creating additional challenges for the cartel and its member states. By suppressing standard oil industry data disclosures and using oil tanker locational “spoofing” and other forms of subterfuge to obscure export flows, Moscow has made it more difficult for OPEC to monitor Russian production and export activity. And OPEC producers do not appear pleased by the development of a novel sanction designed to constrain oil export revenues—the price cap—which Russian atrocities precipitated.

OPEC has seen through Moscow’s deceptive efforts to manipulate the cartel into rebalancing the market while avoiding any real cuts itself.

To maintain support of OPEC in the face of these growing strains and induce them to cut, Moscow has pursued a strategy of scaremongering and deception. They have misrepresented the price-cap as a “buyers’ cartel”—an absurdity, since EU/G7 countries are forbidden from buying Russian oil—and claimed Washington intends to use it against all OPEC producers. And they announced in February what appears to have been a sham unilateral output cut, intended to induce other OPEC partners to cut as well. But OPEC has seen through Moscow’s charade and required an actual cut in exchange for reciprocal support. A reduction in Russian crude exports appeared to be underway in July. But with the substantial recent rise in Russian refining runs, it’s likely that the cut in crude exports will be largely offset by an increase in product exports.

* * *

High oil prices will now put the robustness of EU/G7 sanctions to the test.

Moscow’s complementary circumvention strategies—expanding its sanction-proof fleet to the extent it can and falsifying price attestations to ship non-compliant cargoes on mainstream tankers when no shadow tankers are available—have yet to be put fully to the test. But this may soon change as Urals prices rise above the price cap. Despite their weaknesses, Moscow’s circumvention strategies retain the potential to severely undermine sanctions. Fortunately, however, EU/G7 policymakers now have in place the legal framework needed to render both these strategies largely ineffective and further constrain Moscow’s access to critical windfall revenues.

To avoid wholesale subversion of sanctions, specific adjustments need to be made to how the sanctions framework is being implemented.

But to work effectively and avoid wholesale subversion, specific adjustments need to be made around how that framework is being implemented. If made, these adjustments can significantly increase fiscal and psychological pressure on the Kremlin leadership—all without increasing inflationary pressures in the energy markets. But if policymakers do not move swiftly to make adjustments, they risk seeing the full-scale subversion of Russian oil sanctions and unleashing further upward pressure on energy prices.

These four measures can make a substantial difference.

Drawing on detailed analysis of the first half year of sanctions, this report recommend four specific, high-impact adjustments to the current framework that can help assure sanctions are effective, not subverted.

Recommendation #1: Lower the price cap

The arguments in favor of a lower price cap are overwhelming, while the rationale behind the higher cap has now fallen away.

Last autumn, the main argument against setting a lower price cap was that Moscow might retaliate by engineering a supply crisis that would spur inflation and potentially trigger a recession. This, in turn, would erode support for Ukraine. Since then, however, the risk of oil weaponization has greatly receded (see Introduction), removing the main argument in favor of a higher price cap. At the same time, additional arguments supporting a lower cap have only gotten stronger, namely:

sanctions have been having a tangible impact;

Moscow has routinely been willing to export at prices far below $60 a barrel;

the ruble’s recent collapse lowers Russia’s breakeven oil price, making it easier for producers to cover costs at lower oil prices;

Moscow’s large tanker gap means most of Russia’s seaborne exports remain exposed to the price cap; exposure levels could rise above 80% if insurance verification is implemented (see recommendation #4);

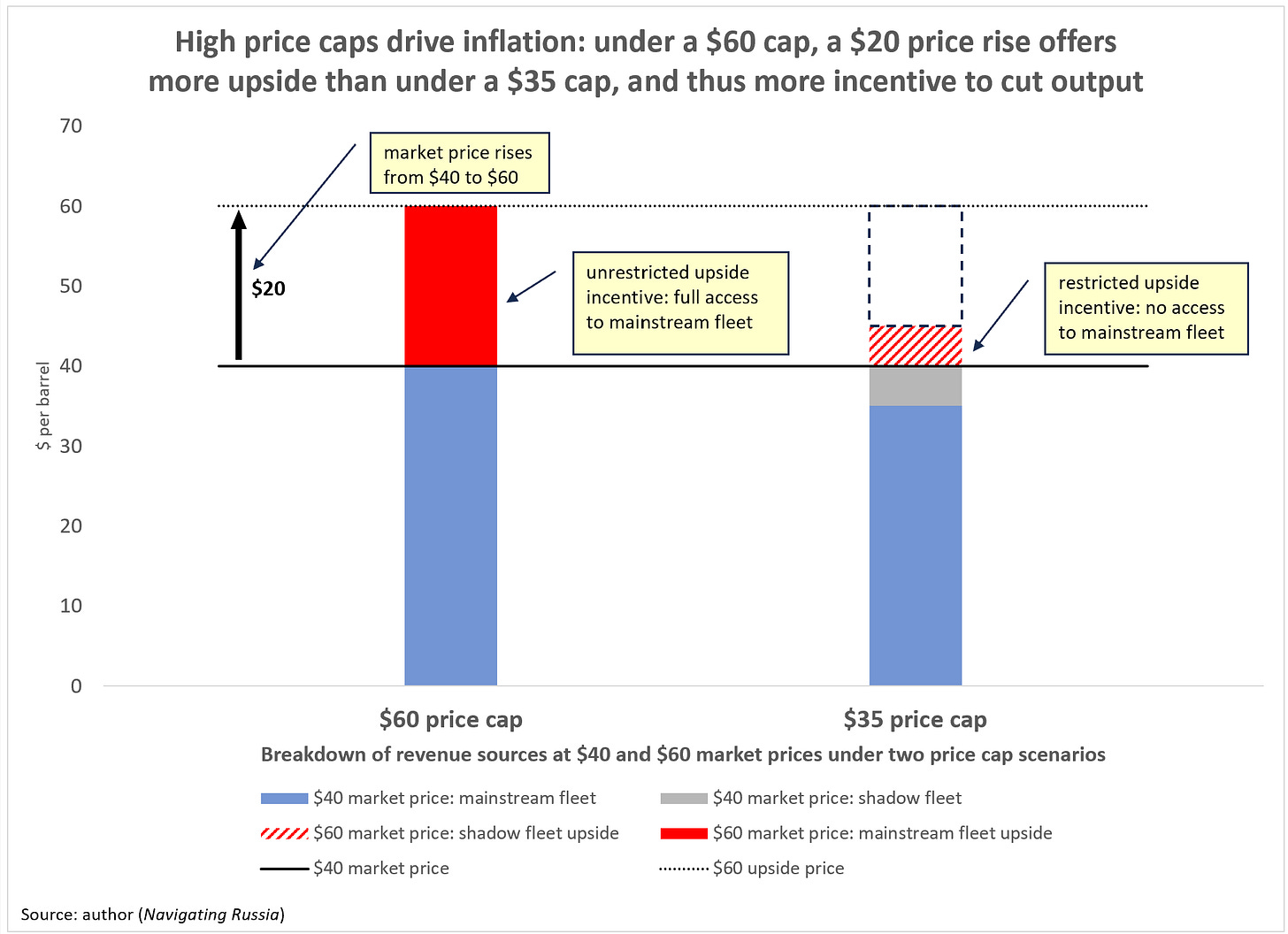

a higher price cap has, contrary to intent, ended up increasing Moscow’s incentive to cut output to push up prices, rather than decreasing it.

As weaponization risk receded over the winter, and the discount pushed market prices for Urals down to $40, an unexpected thing happened. The high, $60 price cap, that was intended to reduce incentives for Russia to cut output ended up, perversely, increasing them (see Executive Summary Figure 14). The high price cap gave Moscow unrestricted upside potential of $20 per barrel. Put otherwise, if the market price rose from $40 to $60, Moscow would be able to capture 100% of that $20 upside, since the high price cap ensured access to mainstream tankers for cargoes priced up to $60.

Had, by contrast, the price cap been lowered, say, to $35, it would have limited Moscow’s ability to capture upside value from rising prices, since its sanction-proof fleet was only large enough to move a fraction of its exports at full market prices. The rest would have to be transported by mainstream tankers at the capped price. With less to gain from higher market prices, Moscow’s incentive to cut its own output (and badger OPEC to do likewise) would have been significantly weaker.

The same would hold true today. If price caps were dropped to $35, it would weaken Moscow’s incentive to keep any cuts in place. Moscow might revert to doing what it did last time it faced low effective prices and maximize output.

Recommendation #2: Combat price attestation fraud by developing a “whitelist” of approved traders.

It makes little difference at what level the price cap gets set if price attestation fraud goes unchecked. Moscow would have enough unrestricted access to mainstream tanker capacity to keep export volumes whole, regardless of price. That, in turn, would create even greater incentives for Moscow to push for higher pricing, since it could capture 100% of revenues at any price.

This makes price attestation fraud by bad-faith brokers as great a threat to sanctions as the shadow fleet—perhaps even greater. Policymakers need more effective measures for preventing pricing fraud. Lessons should be drawn from the apparent use of fraud at Kozmino earlier this year.

The critical task of screening out bad-faith traders should not rely solely on “know-your-client” due diligence by mainstream tanker owners.

The crux of the problem is that the burden of identifying potentially bad-faith traders is left to ship owners. They are required to conduct their standard “know-your-client” due diligence when engaging customers and provided red-flag guidelines on what to watch out for.

This approach is unworkable. Standards of due diligence and the resources for conducting it will vary significantly from one ship owner or operator to the next. So too do the potential consequences of grossly negligent diligence. Invariably, some bad-faith traders will remain in the mix, potentially a large number.

Enforcement agencies should pro-actively develop whitelists of allowed traders.

To effectively combat attestation fraud, enforcement agencies need to play a more proactive role in screening out bad actors. They could start by developing a “whitelist” of broker/traders authorized to provide pricing information. This whitelist could be made up of well-established commodity trading groups based in EU/G7 countries, and therefore subject to legal action for violating sanctions and providing false pricing information. Moreover, as EU/G7 entities, they would be required to retain and, if necessary, disclose underlying transaction documents to authorities.

For a mainstream EU/G7 owned or insured tanker to transport Russian oil, it must receive its price attestation from a whitelisted trader. Failure by ship owners to obtain price attestations from a whitelisted trader would be considered a violation of sanctions. Many EU/G7 traders have extensive experience trading out of Russia and some may welcome the opportunity to re-engage, if clear guidelines are provided by enforcement authorities. That might not eliminate bad-actor risk entirely but should go most of the way.

Recommendation #3: Crack down on the involvement of EU/G7 entities in the sale of used tankers to Russian or undisclosed buyers

One way to limit the expansion of Russia’s shadow fleet is by further constraining supply. Shadow tankers are often purchased from mainstream operators—many based in the EU/G7—during the process of fleet renewal. There is plenty of consternation among some ship brokers about lack of compliance by more risk-friendly competitors. As one commented: “So people who think they can ignore the rules and still go out and do business, I say ‘more fool them’, and I hope they have a lot of sleepless nights and wake up with a knock on the door.”1

Enforcement agencies should crackdown on the involvement of any EU/G7 entities in the sale of used tankers either to Russian or undisclosed buyers. This should include not only the sale of EU/G7 owned tankers but the involvement of any EU/G7 brokers, banks or other advisors in such sale. Authorities should encourage whistleblowing to help generate leads. Investigating a case would have a chilling effect on the trade, especially if its results in a substantial fine or conviction.

Even with such prohibitions and stepped-up scrutiny, sales by EU/G7 ship owners into the used market will likely continue to find their way into the Russia shadow trade. But these deterrent efforts can slow down the transaction flows and increase costs for Russian buyers by introducing a risk premium and additional intermediaries.

* * *

Conclusion of Executive Summary: No more oil windfalls—hastening Russia’s retreat from Ukraine

Together, all these recommended measures aim to do one thing: tightly constrain Moscow’s access to windfall oil revenues. Like other sanctions, this will help erode Russia’s economic resilience, diminishing its means for financing its war of aggression against Ukraine.

At the same time, Russian oil sanctions are different from other sectoral sanctions and have the potential for a qualitatively greater impact. Periodic oil windfalls play a unique and indispensable role in the political economy of the Putin regime. They renew regime vitality, restore appetite for risk and help maintain cohesion among fractious elites.

Oil sanctions, if assertively implemented, can dim Moscow’s hope for renewed access to oil windfalls. That would unsettle Kremlin leaders and help increase their risk aversion. Such heightened caution was on display last December, when Moscow chose not to weaponize oil. And it was on display more recently, during the Prigozhin Affair, when Putin shied away from direct confrontation. It can also hasten the day Moscow changes its calculus and recognizes that a withdrawal from Ukraine has become its best option. That prospect makes it worth taking pains to ensure oil sanctions work as well as they can.

Measuring the Shadows

Introduction: The safe bet—Moscow opts to counter oil sanctions with circumvention, not weaponization

Last December, Moscow decided against weaponizing its oil exports in response to new sanctions, opting instead for a lower-risk strategy of circumvention. Now, as Russian oil rises above the price cap, EU/G7 policymakers have the tools needed to counter Moscow’s evasion efforts and enhance the impact of sanctions, but only if they take specific measures to improve how sanctions are implemented.

The “diskont”

“You need to sort out this discount problem, so it doesn’t cause any problems with the budget.” Those were the instructions Vladimir Putin gave last January to Alexander Novak, his deputy prime minister in charge of energy. Novak had been briefing Putin on the painful $30+ discounts that Russian exporters were then having to offer to secure firm demand for Urals grade crude. This “diskont”—as Putin referred to it—was many times greater than the one-to-two-dollar spreads to benchmark Brent typical in the past. With oil revenues the single largest contributor to the Russia’s budget, Putin was right to be concerned.2

“You need to sort out this discount problem, so it doesn’t cause any problems with the budget.” — Vladimir Putin to Alexander Novak, January 2023

The discount was largely the result of the abrupt ending to Russian oil’s 145-year romance with its most important export market, Europe. Over many decades, Russia had built out a massive infrastructure of pipelines and ports to deliver crude and refined products to a sprawling European customer base. Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, however, European customers gradually began shunning Moscow’s oil—culminating in a full-scale embargo this past winter.

An historic shift in global trade patterns ensued. Hundreds of tankers loading each month at Russia’s Baltic and Black Sea terminals no longer set course Hamburg, Rotterdam, or Augusta. Instead, in search of new buyers, they embarked on long voyages to distant markets, mostly East of Suez. As Novak would explain to Putin, shippers were taking advantage of the tainted status of Moscow’s oil to gouge Russian exporters on freight rates. Shippers were reportedly charging as much as $15 a barrel to transport Russian crude from the Baltic to West Coast India, ten times what it would have cost a year earlier.3

But high shipping costs weren’t the only thing behind the discount. In addition to being much further away, the markets still open to Russia were smaller, less familiar and more concentrated. The bulk of Russia’s dislocated crude was going to a single buyer, India. Such a concentrated market weakened Russia’s pricing power, allowing Indian traders to drive hard bargains. Unless Moscow could reduce the glut of Russian oil now pouring into the Indian Ocean basin, or find a broader range of buyers for it, the dreaded diskont looked destined to persist.

* * *

Last year, Moscow struggled to develop a strategy for countering oil sanctions

The EU/G7 sanctions pose the greatest potential threat to Russia’s oil industry since Soviet times. The discount is just one of numerous vexing, often unanticipated problems thrown up by it. The sanctions have forced hard choices on Vladimir Putin, decisions he will not have taken lightly, given oil’s unique place in the political economy of Russia. Oil is the largest contributor to the Russian budget. Russian energy exports generated record revenues in 2022, providing a momentary fiscal buffer against broader sanctions. By contrast, in the first half of 2023, weak oil and gas revenues—down 47% year on year—helped drive a ballooning budget deficit.

But for Putin, Russia’s oil industry is about more than just balancing the budget—it provides the very lifeblood of this authoritarian system of rule. Throughout Putin’s tenure in power, Russia has, from time to time, reaped massive windfall revenues from periods of high oil prices. Putin has single mindedly promoted these windfall opportunities and covetously consolidated control over the hundreds of billions of dollars in surplus revenues they have generated. Oil windfalls provide him the means to buy the loyalty of elites, bully enemies and paper over failures of an otherwise anemic economy. Oil windfalls have also bank-rolled adventurism abroad, including Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. The Kremlin’s appetite for such adventurism is never higher than when its coffers are flush with petrodollars.

For many months, Moscow has struggled to develop a coherent strategy for countering sanctions. When oil sanctions were first mooted by the EU in the Spring of 2022, Kremlin officials were scathing, branding sanctions as “suicidal” for Europe. They confidently asserted that Moscow would build new pipelines and ports and reroute Russian oil to more promising markets. But their bravado soon faded over the summer, as Kremlin officials came to grips with just how deeply dependent Russian oil exports were on EU/G7 markets and marine transportation services. If sanctions went ahead, there would be no quick or easy fixes.

With no quick fixes to hand, the Kremlin began threatening to weaponize oil exports…

Soon, Kremlin officials were adopting a different, more menacing tone as they made thinly veiled threats to weaponize oil exports. These threats echoed what was already happening with Russia’s European gas exports. For months, Moscow had been methodically engineering a gas supply crisis in Europe, sending markets into a panic. By late summer, European gas prices had skyrocketed to 30 times recent averages. An anxious Europe braced for a cold, dark winter.

In the months leading up to sanctions, Moscow looked poised to weaponize oil, just as it was doing with gas (and grain). Analysts projected price spikes to $350. Economists feared a supply shock could tip the global economy into recession. Markets watched anxiously to see how Moscow would respond as the December sanctions deadline approached.

…but eventually backed away from this high-risk option.

Then something remarkable happened. As crude sanctions came into force on December 5th, Moscow fell silent. Days passed and then weeks, with no formal response. Conflicting rumors circulated of draft decrees containing various retaliatory measures. But when a presidential decree was eventually issued at the end of December, it proved underwhelming. It did little more than forbid the mention of price caps in sales contracts. It included no measures that would in any way constrain the supply. Analysts scratched their heads, markets yawned, Urals slumped, and Russian export volumes continue to ship unabated.

Moscow’s climbdown came in the face of a rapidly deteriorating risk environment—too many things were going wrong all at once.

For policymakers in charge of Russian oil sanctions today, understanding the significance of Moscow’s December climbdown is essential for making good policy decisions going forward. And for those responsible for Kremlin threat assessment more broadly, Putin’s response to the challenge of oil sanctions makes for a valuable case study in his diminishing appetite for risk.

Last December’s strategic decision not to weaponize oil exports was made against the backdrop of a rapidly deteriorating risk environment for the Kremlin. Things had started going wrong across a number of fronts. First, Moscow’s gas weaponization policy—which looked so promising in the early autumn—by December was backfiring badly, thanks largely to European resourcefulness, resilience, and unity. Strategic gas partnerships stretching back 50 years were torched overnight. Gas prices were tumbling. The Russian budget—which ran a surplus for the first eleven months of 2022—suddenly lurched into deficit.

As for the oil industry, it wasn’t just the discount that was causing trouble. As crude sanctions came into force, concerns over the price cap caused Chinese state-owned, Greek, and other mainstream tankers to abruptly stop loading at Russia’s largest Pacific port. Russian exporters struggled to mobilize the modest number of shadow tankers needed to fill the gap. Pacific export volumes collapsed by half. While the mainstream fleet continued to call on Russia’s major western ports, events in the Far East were an unsettling sign of how heavily dependent Russia remained on EU/G7 marine transportation.

Meanwhile, Moscow’s covert effort to buy up second-hand oil tankers was bumping up against constrained supplies. The price for a 15-year-old Aframaxes class vessel had climbed nearly 130% over the preceding 12 months. To top it off, Putin’s hopes that OPEC would boost slumping oil prices at its December meeting were dashed when the cartel opted not to cut. In a revealing moment of discord, OPEC ministers chose, instead, to wait and see whether Moscow might save them the trouble of cutting by following through on threats of a large, unilateral cut. On top of all this, on the battlefield, military setbacks were mounting, forcing a mobilization that was both unpopular and poorly executed

Weaponizing oil was a high-risk move that could easily go wrong—just as gas weaponization had—but with far more serious consequences for regime resilience.

It was against this backdrop of spiraling risk that Kremlin leaders were being forced to respond to the imposition of sanctions. In the best of circumstances, weaponizing oil would be a high-risk option. Without OPEC firmly on board and global oil demand robust, a unilaterally engineered price spike could quickly falter and fade. And when it did, Moscow would be left in a far weaker position, with revenues down, market share lost, OPEC ties strained and shut-in production capacity steadily deteriorating. Moscow’s failed gas gambit has just demonstrated how easy it was for an engineered supply shock to go wrong. What’s more, the leverage Russia enjoyed over European gas markets was far stronger than over global oil. To gamble, and lose, with Russia’s gas industry was a painful act of hubris. But to then play dice with Russia’s indispensable oil industry was a potentially fatal act of folly.

Putin would well understand that getting oil policy wrong in the middle of a war could jeopardize the regime’s stability, as the Soviet leadership had demonstrated in spectacular fashion. In the face of mounting risk, customary Kremlin conservatism kicked in, dampening the appetite for a confrontational, high-stakes gamble with oil. And that appetite looks unlikely to return anytime soon.4

Moscow opted, instead, to pursue a lower-risk, anti-sanction policy centering around circumvention rather than confrontation.

Having set aside weaponization as too risky, Moscow decided instead to pursue a much lower-risk policy of circumvention. This involves maximizing output and then trying to sell as much as possible outside of the price cap regime. This strategy does not pack the potential recession-triggering punch of weaponization, but nor does it run the risk of backfiring spectacularly.

In pursuit of circumvention, Moscow and its trading affiliates have experimented with a range of tactics. Some of these are clandestine in nature—such as “dark” ship-to-ship transfers and the locational “spoofing” of tankers. These methods of subterfuge at sea—a curious blend of steampunk and cyberpunk with a bit of Bond thrown in—have captured the public imagination—and understandably so. But when measured against the immensity of Russia’s export volumes, such clandestine operations are marginal at most. They simply don’t offer scalable solutions for circumventing the price cap. Consequently, they’re not the strategies Moscow is banking on.5

Moscow’s 3 core strategies for circumventing sanctions

Instead, Moscow has been focusing the main thrust of its efforts on three core anti-sanction strategies.

The first involves assembling a stand-alone, “sanction-proof” fleet of oil tankers. This fleet, made up of state-owned Sovcomflot oil tankers along with an expanding roster of “shadow tankers,” relies mainly on effective immunity from sanctions—rather than subterfuge—to circumvent the price cap. The great challenge Moscow faces is: can it assemble a large enough fleet to meet Russia’s immense tanker capacity needs?

The second strategy, which is complementary to the first, focuses on exploiting the global mainstream, price-cap-compliant fleet. It seeks to use mainstream tankers to carry cargoes priced above the cap by providing ship owners with fraudulent pricing. It relies on a known vulnerability in the price-cap compliance regime that can result in mainstream ship owners relying on pricing information from bad-faith oil traders. If left open, this loophole could allow Moscow to fully subvert the price cap. The challenge for Moscow, however, is that stepped-up enforcement of existing price-cap rules could quickly close this loophole.

The third strategy is not really a new one, but dates back to Moscow’s 2016 decision to collaborate with OPEC to manage global oil prices. Moscow is continuing to rely on OPEC collaboration to regulate prices, rather than pursuing an aggressive, value-over-volume policy involving large, unilateral cuts. What’s changed, however, is the sudden upward jump in Russia’s fiscal breakeven oil price, along with Moscow’s more aggressive use of cynical scaremongering and deception against its OPEC partners. Moscow was contriving to get the producer cartel to cut, while Russia maintained full output, but OPEC has strong armed Moscow into making cuts as well…or so it seems.

With Urals now trading above the cap, Russia’s circumvention strategies are now being put to the test…

In recent weeks, these coordinated cuts by OPEC+ have tightened oil markets, narrowing the Urals discount and pushing market prices above the $60 price cap. Moscow’s circumvention strategies are now being put to the test. EU/G7 policymakers possess the sanction tools needed to thwart Moscow’s evasion efforts. That’s thanks in large measure to extraordinary levels of multilateral collaboration and innovation among alliance countries last year.

…and EU/G7 policymakers must improve how sanction tools are being used to ensure they remain effective.

But for those tools to work effectively, lessons must be drawn from the first half year of oil sanction, and specific adjustments must be made in how these tools are used. If made, alliance countries can counter Moscow’s evasion efforts and further erode Russia’s economic resilience. And they can shake confidence inside the Kremlin by dashing hopes in future oil windfalls to revitalize the regime. If, however, lessons aren’t drawn and adjustments not made, sanctions could be at risk of unraveling.

* * *

Contents of the report

Measuring the Shadows explores each of these strategies in detail and assesses their potential for subverting the effectiveness of sanctions. It also offers policymakers a set of specific recommendations—based on lessons learned over the last half year—for improving the implementation of the existing sanctions framework.

The report is broken into seven chapters. The first four concern Moscow’s effort to assemble a sanction-proof fleet.

Chapter 1 examines the central role shadow tankers play in Russia’s circumvention strategy, and how their immunity to the legal and commercial deterrence of sanctions is far more important to Moscow than any subterfuge operations they may occasionally conduct.

Chapter 2 measures the size of the sanction-proof fleet currently active in Russia.

Chapter 3 estimates the number of sanction-proof tankers Moscow would need to keep exports whole and fully sheltered from the price cap. This quantity, it turns out, far exceeds the number of sanction-proof tankers active in Russia. The result is a substantial shortfall—or “tanker gap”—amounting to some two-thirds of the total volume Moscow needs for full export autonomy.

Chapter 4 assesses Moscow’s prospects for closing this tanker gap through recruitment and acquisition. It concludes that closing the tanker gap in any reasonable timeframe is highly unlikely, owing to limited supply, rising costs and a steepening treadmill of attrition.

Chapter 5 examines Moscow’s second, complementary evasion strategy. It traces how, in the early months of 2023, Russian exporters managed to engage mainstream tankers to carry cargoes priced above the price cap apparently by providing them with fraudulent pricing information.

Chapter 6 explores Moscow’s efforts to manipulate its OPEC partners into cutting output to boost oil prices while trying to avoid any substantive cuts of its own.

Chapter 7 details four specific recommendations to safeguard existing sanctions and help them function more effectively:

lowering the price cap, which both reduces Moscow’s oil revenues while also reducing its incentives to cut volumes to boost prices;

combating price attestation fraud by developing a whitelist of approved traders;

cracking down on the involvement of EU/G7 entities in the sale of used tankers to Russian or undisclosed buyers;

requiring ships transiting EU/G7 territorial waters to verify that their spill liability insurance is adequate and current, which can sharply reduce both shadow tanker activity and the risk of a catastrophic accident.

This report concludes that the recent rise in the existing sanctions framework provides policymakers with the tools they need to thwart Moscow’s strategies and impose much greater economic costs on the Kremlin, but only if these tools are used more effectively.

Measuring the Shadows is part of on-going analytical research into Russian oil sanctions. Its key conclusions are based in part on detailed modelling of Russian shipping patterns using open-source data. Its judgements are informed by the author’s 25-year career in the global financial markets—including extensive professional exposure to Russian oil executives and government officials—as well as prior academic training in Russian and Middle Eastern languages and history.

Part 1: Moscow’s “physical” evasion strategy: assembling a sanction-proof fleet

Chapter 1: Russia’s peculiar shadow fleet—evading sanctions through immunity, not subterfuge

The shadow fleet active in Russia today differs from shadow fleets elsewhere. Instead of relying primarily on subterfuge operations to circumvent sanctions, Russia’s “sanction-proof” tankers rely on immunity from the legal and commercial deterrence.

Not all shadow fleets are the same. Moscow’s fleet relies primarily on sanctions immunity rather than subterfuge to circumvent the price cap.

Since last summer, Moscow has been trying to assemble, through chartering and outright acquisition, a fleet of tankers capable of circumventing price-cap restrictions. These tankers would allow Moscow to receive the full market value for its oil when market prices are above price-cap limits set by the EU/G7 alliance. The core of this sanctions-circumvention fleet consists of tankers from Russia’s own state-owned shipping company, Sovcomflot (SCF). Supplementing them is a swelling roster of shadow tankers that have begun lifting oil from Russia over the last twelve months.

Moscow’s shadow fleet is similar in some respects to shadow fleets found elsewhere…

Much has been written about the shadow fleet in Russia. It is often assumed to be similar to the shadow trade in sanctioned oil elsewhere in the world, such as Iran. The comparison is valid, but only to a point. Shadow tankers operating outside of Russia tend to have four distinguishing features:

1. they are old,

2. anonymously owned,

3. focus on sanctioned oil and

4. seek to evade sanctions monitors by engaging in deceptive shipping practices.6

Nearly all shadow tankers active in Russia share the first three characteristics—advanced age, anonymous ownership, and focus on sanctioned oil.

… except it does not rely on subterfuge as its primary means of evading sanctions.

But the fourth characteristic—subterfuge—is not a defining feature of the Russian shadow trade. That’s because, unlike elsewhere, shadow tankers active in Russia do not need to rely on subterfuge to circumvent sanctions. To be sure, some shadow tankers transporting Russian cargoes are involved in subterfuge operations. This has been documented by valuable reporting on incidents of “dark” ship-to-ship transfers, AIS “spoofing” and other deceptive shipping practices.7 And in some cases, these practices are likely being used to smuggle Russian oil into closed markets, like the EU.

But it’s important to keep the scale of these clandestine operations in perspective. The aggregate volumes involved in such physical subterfuge operations normally represent only a few percentage points of Russia’s total seaborne exports. In the greater scheme of Russia’s circumvention strategy, subterfuge operations are, at most, of marginal significance. Moscow is primarily using the shadow fleet in a very different, quite overt way to evade sanctions. And as EU/G7 authorities consider how to allocate limited enforcement resources on Russian sanctions, focusing on tanker subterfuge at sea is unlikely to be the best option. Taking steps to limit overall shadow-tanker activity and combat fraudulent pricing information will have a much higher impact (see Chapter 7).

Most Russian oil transported by its shadow fleet is carried overtly, with no effort at concealment.

The simple reason is that, unlike elsewhere, subterfuge is simply not required to sidestep the sanctions imposed on Russia. Most Russian oil transported by shadow ships today in circumvention of the price cap is carried overtly, with no effort whatsoever at concealment. There are no ship-to-ship transfers, AIS signals remain switched on and undistorted, and cargoes are easy to track from loading to landing.

Many sanctions regimes include a “secondary” sanctions feature, like U.S. sanctions on Iran. That means all parties to a transaction, regardless of their jurisdiction, are subject to sanctions, thus creating a shared need for concealment and subterfuge.

The reason subterfuge is not needed arises from a fundamental difference between the oil sanctions imposed on Russia versus those imposed elsewhere, such as Iran. The Iran sanctions have a secondary component. This allows punitive measures to be taken against third-party entities around the world. The U.S. Treasury can, for example, impose sanctions on third-country importers if they are caught dealing in sanctioned Iranian oil. So, to reduce their risks, third parties handling Iranian oil seek to obscure its origins. Consequently, stealth and subterfuge have become the stock-in-trade of the shadow fleet active in Iran.

But Russian oil sanctions are “primary” sanctions only, with a focus on EU/G7 entities; they thus create an opportunity for third-country entities to openly import Russian oil free from sanctions risk.

But the Russia shadow trade is different. Russia sanctions are primary only. Unlike Iranian sanctions, they apply only to entities based in the EU/G7+ sanctioning countries themselves—not to third-country businesses. So, an importer from a non-sanctioning country faces no legal risk of direct sanctions for trading in Russian oil.8

For Moscow, what matters most is not a tanker’s capacity for stealth, but whether it is immune to the deterrent force of sanctions—whether it has the ability to disregard the price cap openly and with impunity.

Consequently, when it comes to assembling its shadow fleet, the attribute of greatest interest to Moscow is not a tanker’s stealth and subterfuge. It’s something more mundane: it’s a tanker’s immunity to the deterrent force of sanctions—an immunity that renders it “sanction proof.” This quality gives a tanker the ability to openly and reliably transport Russian cargoes priced above the price cap without concern for legal or commercial repercussions. In short, they can disregard the price cap with impunity. Together, these tankers form what can be called Moscow’s “sanction-proof fleet.”

Deterrence takes two forms: legal and commercial.

In the scheme of Russian oil sanctions, deterrence comes in two forms: legal and commercial. Whether a ship is subject to these deterrents depends on two things: (1) where their owners are based and (2) who provides their critical marine services—especially mortgage finance and liability insurance.

(1) Legal deterrence is limited to EU/G7 ship owners; violating sanctions can land them in court.

Ship owners based in the EU or G7 are subject to legal deterrence. If they violate the price cap, they are violating the law of the country in which they are based. If caught, they will likely end up in court.

(2) Commercial deterrence affects any ship owner worldwide who relies on EU/G7 entities for key marine services, such as ship financing and insurance.

Ship owners based outside price-cap alliance countries don’t face legal action for violating sanctions. But they can face painful commercial consequences. Most ship owners based in non-sanctioning countries rely on EU/G7 entities for certain critical marine services. If those ship owners violate the price cap, their EU/G7 marine service providers are obligated by law to terminate their service arrangement.

In some cases, those services might be easy to procure from providers outside the EU/G7. But not all. For example, EU/G7 banks have a broad global footprint in the ship mortgage sector. If a non-EU/G7 ship owner funded by a European bank violates sanctions, they could find themselves forced into a painful loan restructuring. For some ship owners, the prospect of a loan restructuring will be sufficient to deter them from violating sanctions.

The EU/G7 service sector with the broadest global footprint is marine insurance, which provides mandatory spill liability (P&I) coverage to some 95% of the global fleet through the Europe-headquartered International Group of P&I Clubs

As significant as EU/G7 may be in ship financing, the EU/G7 marine service sector with by far the broadest global footprint is marine insurance (see Figure 1). Specifically, it’s the highly specialized area of oil spill liability (“P&I”) insurance, which is mandatory for oil tankers. Some 95% of the global tanker fleet obtain their P&I insurance through a quasi-monopolistic network of not-for-profit, mutual assurance societies called the International Group of P&I Clubs (the “IG”).

Comparable alternative coverage at scale does not exist, creating a strong commercial deterrent to violating sanctions…

Because nearly all the principal clubs are based in EU/G7 countries, the IG requires all insured vessels to comply with Russian sanctions as condition of insurance. And because comparable alternatives to IG P&I coverage simply don’t exist at scale, the IG enjoys a near-monopolistic grip on the mainstream tanker market. IG coverage is often compulsory for securing loans from mainstream banks, entry to key ports and charter opportunities with large oil concerns. Consequently, fear of losing it acts as a powerful commercial deterrent to violating the price cap.

…which may help to explain why China’s state-owned tanker fleet, which is insured through the International Group, has—apparently out of an abundance of caution—stopped lifting oil from Russia since the introduction of sanctions.

As an illustration of this, consider the case of COSCO, China’s state-owned shipping giant. COSCO has China’s largest tanker fleet, which it insures through the IG. In 2019, however, COSCO went through a painful ordeal when OFAC imposed sanctions on a key subsidiary of its tanker business in connection with the Iran trade. The subsidiary’s business was severely disrupted as Western banks, traders and P&I insurers temporarily withdrew services. After eight months of back and forth, sanctions were dropped. Memory of that painful experience may help explain the conservative approach COSCO is taking to the Russia trade. Prior to sanctions, COSCO tankers regularly carried Russian oil cargoes. Since December 5, it’s hard to find a single COSCO tanker that has lifted from a Russian port.

Tankers either owned or financed by EU/G7 entities will also usually be insured by the IG. That, at least, is the case for pretty much any of the medium-to-large-size tanker classes (i.e., over 25,000 deadweight tons) that handle nearly all the Russian export trade. Mainstream European or American lenders will be reluctant to lend without proper insurance. Without taking on large amounts of debt, EU/G7 ship investors cannot get the levered returns they seek.

But for EU/G7 ship owners, having an IG P&I policy isn’t just enabling levered returns. It’s also about managing catastrophic risk. These investors are based in countries with relatively robust legal systems able to impose large punitive damages on ship owners for catastrophic spills. And under international conventions, ship owners bear ultimate liability for oil spills. So, to take on ownership risk, EU/G7 investors will want to be sure their insurance provides bullet-proof protection from unlimited liability. When it comes such protection, along with related matters such as track record of payouts, financial transparency, capital adequacy and good corporate governance, there is simply nothing comparable to P&I coverage from an IG club.

The small segment of the global fleet not insured by the International Group possesses the immunity to sanctions that Moscow seeks for its shadow fleet…

Those tankers not insured by the IG, then, tend also to be neither owned nor financed by EU/G7 entities. For Moscow, that’s a charmed combination. This lack of ownership and service ties to sanctioning countries endows these tankers with the effective immunity to sanctions that Moscow seeks. It’s these tankers that can carry cargoes priced above the price cap—no questions asked—and face no legal or commercial consequences for doing so. They are the “sanction-proof” tankers Moscow seeks to assemble into a fleet large enough to transport all Russian oil exports free from price-cap exposure.

…making insurance status a fairly accurate litmus test for distinguishing between mainstream and sanction-proof tankers in the Russia trade.

For those observing tankers loading out of Russia and wanting to distinguish which are sanction-proof and which are not, the vessel’s insurance provides an easy, nearly foolproof, litmus test. If a tanker is insured for P&I through the IG, it’s almost certainly a mainstream, price-cap compliant tanker. If it doesn’t carry IG P&I, it’s very likely to be a sanction-proof tanker able to transport non-price-cap-compliant cargoes without regard for sanctions

Chapter 2: Measuring the Shadows—how big is the sanction-proof fleet in Russia?

Despite substantial growth over the last year, Moscow’s fleet expansion program remains far from its goal of export autonomy and appears to be slowing in the early summer.

Can Moscow assemble a large enough fleet to close the “tanker gap?”

This chapter examines a critical question for the Kremlin—and EU/G7 policymakers, too: can Moscow assemble enough sanction-proof tankers to meet most of or all its export needs? We’ll start by measuring how many sanction-proof tankers are already active in Russia. Next, we’ll estimate how many Russia would need to form a stand-alone fleet capable of sustaining recent export volumes free from any price cap limitations. As we shall see, there is a sizeable capacity gap between what Moscow currently has and what it needs. Finally, we’ll assess Moscow’s prospects for being able to close this “tanker gap” in any practical timeframe. Among other things, this assessment will consider aggregate costs and available supply in the used tanker markets.

Two categories of tankers make up Russia’s sanction-proof fleet: state-owned Sovcomflot tankers and “shadow fleet” tankers.

Since February 2022, most tankers loading in Russia continue to be from the mainstream fleet. They are either EU/G7 owned, financed, or insured—in some cases all three. This means they will have strong legal and commercial incentives to observe sanctions by being price-cap compliant.

Apart from this mainstream, price-cap compliant fleet, a parallel “sanction-proof fleet” has been active in growing numbers in the Russia trade since the summer of 2022. It’s made up of two categories of tankers: those from state-owned Sovcomflot and the so-called “shadow fleet” (see Figure 2).

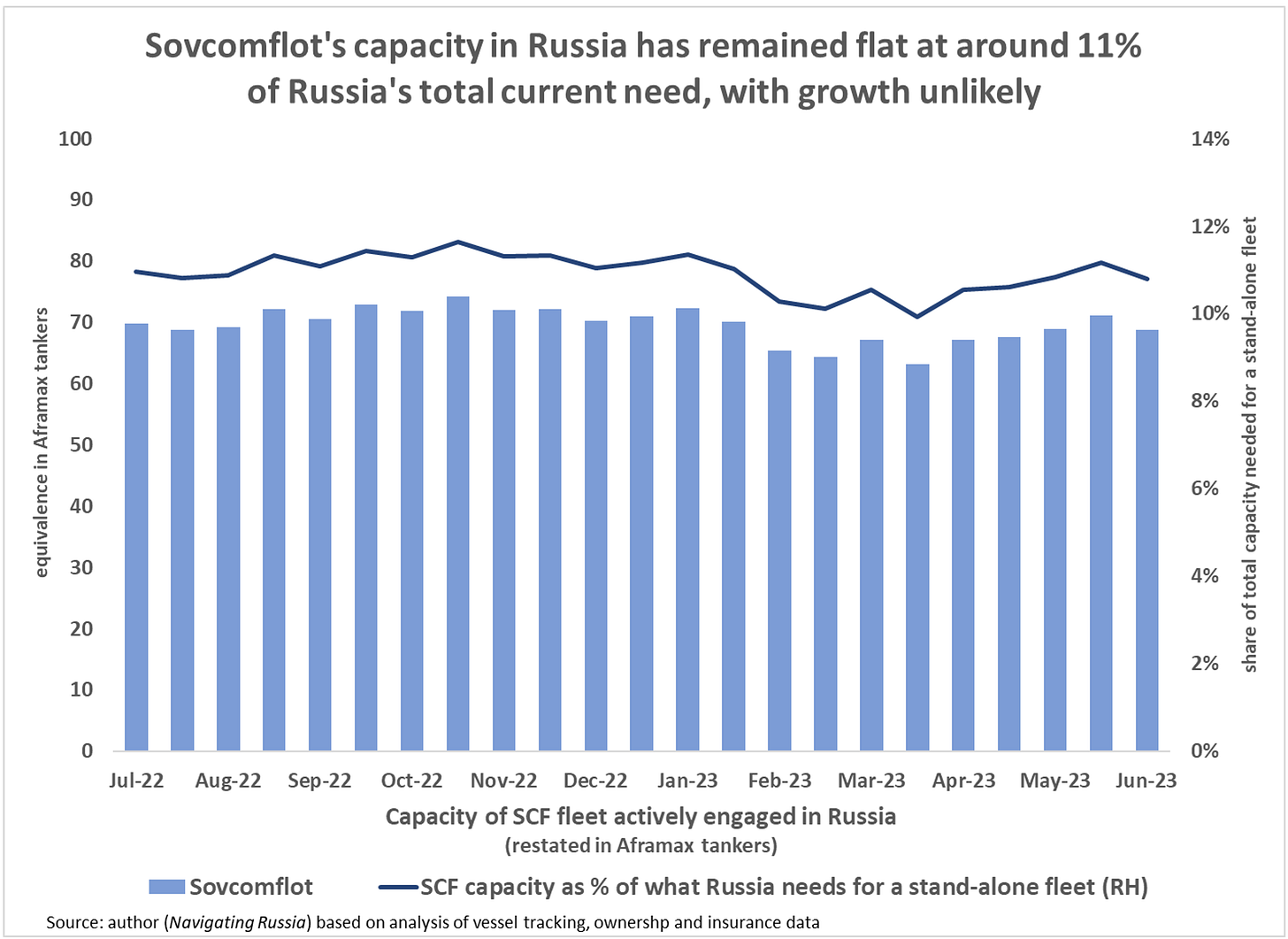

The capacity of Sovcomflot tankers active in the Russia trade has remained stable over the last year, averaging the equivalent of around 70 Aframax tankers.

Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, tankers from Russia’s state-owned shipping company, Sovcomflot (SCF), were part of the mainstream fleet. They were insured by the IG and financed by Western banks. But when SCF was sanctioned in March 2022, the IG cancelled their insurance and Western banks pulled their loans.

Now, with no residual ties to EU/G7 service providers, SCF vessels are able to transport non-price-cap-compliant cargoes with impunity. Over the past year, the capacity of SCF vessels involved in the Russia trade has remained stable and equivalent, on average, to the capacity of 70 Aframax tankers (see Figure 3).9

The source of growth for Russia’s sanction-proof fleet has come from a surge in “shadow tankers” into the Russia trade.

In addition to Sovcomflot tankers, the second category of tankers making up Russia’s sanction-proof fleet are shadow tankers. The roster of shadow tankers engaged in Russia has expanded significantly since the summer of 2022. Like SCF, they have no apparent reliance on EU/G7 finance or insurance. Unlike SCF, however, their ultimate beneficiary ownership remains largely anonymous. Their owners of record are typically single-ship shell companies, registered in off-shore tax havens, whose ultimate beneficiary ownership is difficult to determine based on publicly available information.

Shadow fleet tonnage active as of June 2023 equaled that of some 135 Aframax tankers

Since summer 2022, the capacity of shadow fleet tankers active in the Russia trade has expanded significantly, by the equivalent of some 110 Aframax tankers. By mid-June 2023, the total carrying capacity of Russia’s active shadow fleet equaled around 14.5 million deadweight tons, or the equivalent of 135 Aframax tankers.10 This capacity is distributed among some 163 different shadow tankers currently active in Russia, with deadweight tonnage ranging from 30,000 to 165,000 tons.

Shadow tankers active in Russia have had a mixed record of consistent dedication to the Russia trade.

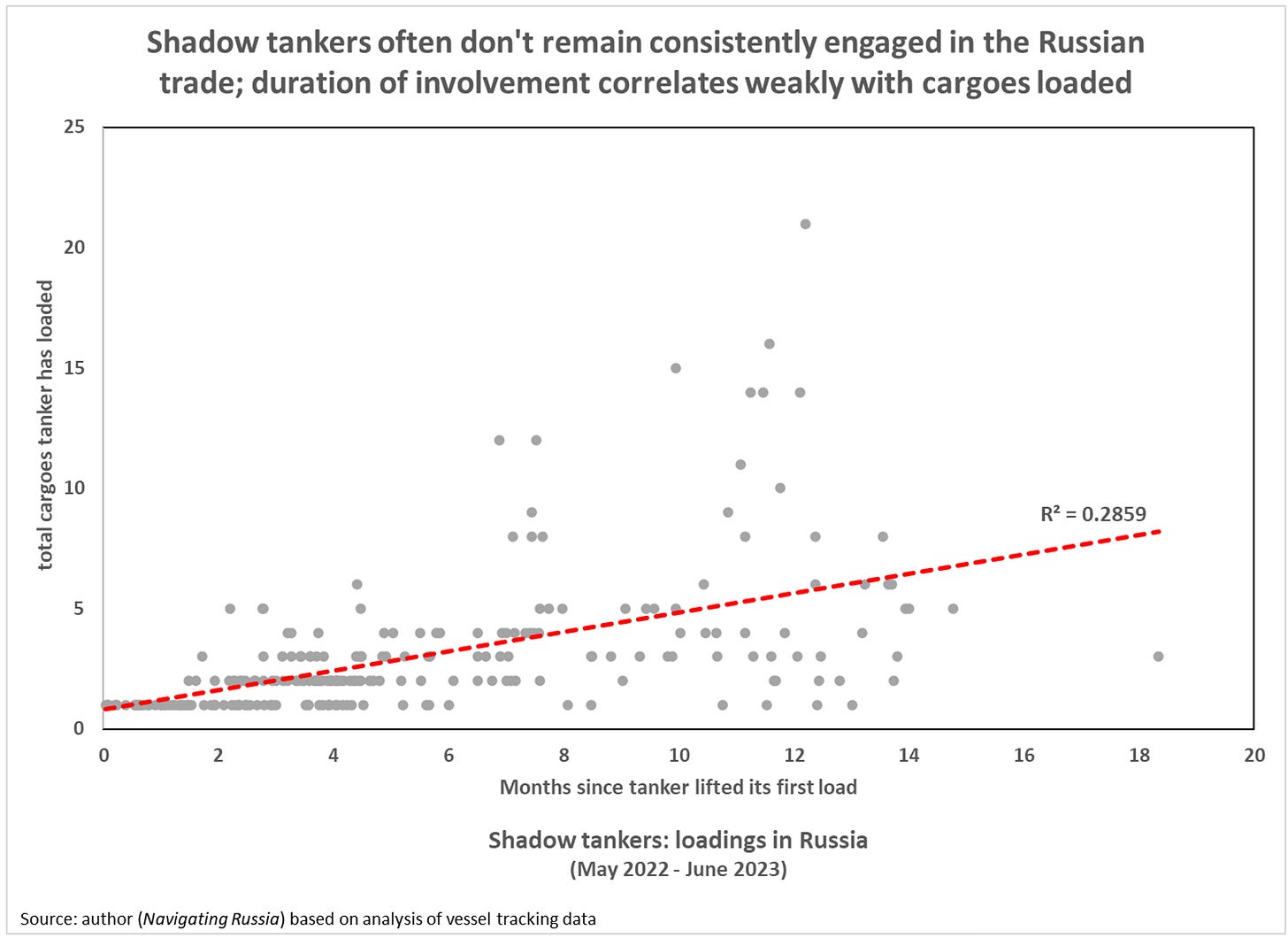

Moscow will be aware that the shadow tankers engaged in the Russia trade have a mixed track record of consistent engagement. Among tankers active in Russia through mid-June 2023, well over half (57%) had loaded only once or twice in Russia since mid-March 2022. And fewer than a third (29%) had built anything resembling a solid track record of dedication to the Russia trade by lifting at least four times or more, with only a handful lifting ten or more times over this period (see Figure 5).

The low percentage of tankers with established track records can’t just be explained away by the relative novelty of shadow tanker activity in Russia. As Figure 6 shows, there is a weak correlation between the number of months a shadow tanker has been engaged in Russia and the number of Russian cargoes it has loaded (R2 = 0.2859). Some tankers have managed a dozen loads in fewer than 7 months. Others started lifting over a year ago but have managed only two or three loads since.

This lack of consistent dedication to the Russia trade comes both from the opportunistic pursuit of business in other markets…

What explains this lack of consistency? Part of it appears to be the opportunistic nature of some of the shadow tanker owners. Russia is just one of several places where they seek business, and they move in and out of the Russia trade as it suits them. Many appear to avoid time charters—long-term leasing arrangements—preferring to charter on a spot basis.

And the Russia trade simply may not suit some shadow tanker owners, even if the rates are lucrative. It can, for example, pose certain risks and burdens not found in the Iranian trade. Routes can be long and demanding, exposing crews and vessels to harsh winter conditions and ice hazards in the Baltic. By comparison, voyages from Iran to India or even China can be far less taxing. Lifting from Russia’s Western ports also brings shadow vessels into European territorial waters, which may expose them to greater risk of seizure if they have fallen afoul of secondary sanctions imposed on Iran or other regimes.

…and unexpected operational interruptions that shadow tankers are prone to.

But this lack of consistency is also driven, in part, by the high incidence of unexpected operational interruptions to which shadow tankers seem to be prone. These incidents range from collisions to detentions to scrapes with the law. Here is just a sampling of things that have gone wrong in recent months for shadow tankers engaged in the Russia trade:

An 18-year-old Cook Islands-flagged tanker, fully loaded out of Vysotsk, lost power in May while navigating the treacherous Danish Straits, straying from the narrow channel and nearly running aground a mile off the pristine coast of Langeland (see Appendix: A brush with disaster in the Danish Straits—shadow tankers menace the Baltic).

a 20-year-old Panamanian flagged Aframax, laden with Russian oil, lost control and collided with a cargo ship last fall in the congested Strait of Malacca. No spill was reported. It was dispatched to China for repairs where it remains ten months on;

a Vietnam flagged tanker was detained in port by Spanish authorities in February, possibly in connection with banned Russian-origin cargo, and later released;

a 19-year-old Indian registered tanker went into dry dock in Dubai last fall for repairs shortly after unloading its Russian cargo, only to languish there for seven weeks before resuming operations;

a 17-year-old Liberian flagged Aframax began regularly lifting oil from Russia following a seven-week detention in a European port early this year, after extensive deficiencies were uncovered during in a port-state inspection;

and then there’s the case of the 20-year-old, Liberian flagged Suezmax that had just finished unloading its Russian cargo in Sicily last November when the US Treasury imposed sanctions on the vessel and its owner for financing Hizballah and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. The vessel managed to slip out of port and avoid detention, but has remained at anchor in the Eastern Mediterranean ever since.

Such frequent troubles are no mere coincidence. As we shall see below, it’s the inevitable result of a business model built around a high appetite for risk and an aggressive attitude towards compliance-related cost-cutting. So long as Russia choses to rely on the shadow fleet, it will need to factor in an elevated level of unreliability into its plans.11

To ensure more tankers dedicate themselves exclusively to the Russia trade, Moscow appears to be covertly funding the acquisition of shadow tankers rather than relying on market forces to ensure an adequate supply of shadow tanker capacity.

It is in Moscow’s interest to reduce this risk of unreliability and inconsistency. Normally, exporters could manage this risk by engaging tankers in long-term time-charters. That option, however, may not be widely available in the shadow tanker market.

But there is an alternative to time charters when it comes to ensuring availability of tankers: owning these vessels outright. Senior Russian officials have long been discussing the need for Russia to assemble a proprietary fleet as well as the formidable financing needs this would entail.12

It’s very likely Moscow has begun acting on these plans. A remarkably high percentage of tankers active in Russia—some 82%—have changed hands since March 2022 (see Figure 15 below). How many of these sales represents covert Russian buying can’t be determined from publicly available information. Some sales were almost certainly to non-Russian buyers and conducted in the normal course of shadow fleet renewal. By its nature, the shadow fleet has high rates of turnover. But it’s likely that at least some of these purchasers—perhaps a large portion of them—are covert Russian buyers, an observation echoed by some ship brokers. If so, it would represent Moscow’s efforts to secure higher levels of shadow fleet commitment to the Russia trade by gaining control of tankers through direct ownership (a more detailed discussion of the costs and challenges of Moscow’s apparent acquisition program can be found in Chapter 4 below).

The pace of shadow-fleet expansion was highest over the winter but has slowed significantly since May.

It’s notable, however, that after a strong surge in numbers over the winter, the rate of shadow fleet expansion has slowed significantly from May into July 2023 (see Figure 4 above). This could be just a momentary downturn. But it may also reflect deeper structural impediments that Moscow’s fleet expansion program has begun to encounter, such as a decline in the availability of suitable tankers and rising costs. In Chapter 4, we shall examine these structural impediments in greater detail. First, however, we must estimate a key quantum: how many tankers does Russia need to keep its exports whole and untouched by the price-cap?

Chapter 3: How many shadow tankers does Moscow need in all?

The EU/G7 import ban has doubled Russia’s shipping needs. The Sovcomflot and shadow tankers currently active in Russia covers barely a third of the capacity Moscow needs for a stand-alone, sanction-proof fleet. The result is a gaping “tanker gap.”

Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, some 75% of seaborne oil exports went to EU/G7 countries, principally in Europe.

It’s hard to overstate the significance of the EU/G7 ban on Russian oil imports. They abruptly terminated a 145-year history of Russian oil exports to Europe that has endured through revolutions and world wars. In recent years, Russia’s oil sales to the EU had become what is likely the largest bi-lateral, single-commodity trade in the history of global commerce. And then suddenly, in under a year, it all but disappeared. Such a seismic shift was bound to pose huge challenges to Moscow, and it has.

Chief among these has been the need to find new buyers in markets that are smaller, more concentrated, much more remote, and far less familiar. Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, some 75% of Russia’s seaborn exports flowed to EU/G7 countries. Most of these exports were shipped through Russia’s highly developed export hubs on the Baltic and the Black Sea to nearby destination ports in the EU, UK, and Turkey. Only a trickle flowed East of Suez (see Figure 7).

The EU/G7 ban on Russian imports has forced exports to reroute to new markets East of Suez, nearly doubling Russia’s shipping capacity needs.

From March 2022 through February 2023, the map of Russian exports gradually but profoundly shifted (see Figure 8). In the early months, voluntary self-sanctioning by some importers drove the trend, with the imposition of hard sanctions eventually completing the transformation.

Sanctions have had the smallest impact on Asia-bound flows through Russia’s capacity-constrained ESPO pipeline. Most of these continue to end up in China either directly overland or shipped by sea via Russia’s Pacific ports.

Russia’s much larger westbound flows, by contrast, have been profoundly disrupted. The immense seaborne flows, previously destined for European destination ports, are still exiting Russia via its western ports in the Black Sea and the Baltic. But now they sail past Hamburg and Rotterdam, continuing on to distant markets located mostly East of Suez. These seaborne flows have been augmented by barrels formerly shipped overland to Central Europe via Russia’s Druzhba pipeline. Most of these—some half million barrels a day—have now been rerouted to Russia’s Baltic or Black Sea ports for shipping by sea to new markets far beyond Central Europe. The longer distances to market have roughly doubled the tanker capacity Russia needs to keep it exports whole.

Most of Russia’s dislocated oil has gone to India or Asian trading hubs, with less than 10% going to China

Over half of Russia’s dislocated oil has gone either to India or trading hubs in the UAE and Singapore. Contrary to some reports, however, only a small portion—less than 10%—reaches China (see Figure 9). Several things explain this.

First, Russia’s straitjacket of pipelines and ports forces most dislocated oil westward, making freight costs to distant China unattractive. Russia’s constrained East Siberian pipeline system doesn’t allow significant amounts of dislocated oil to be moved overland to China or the Pacific coast.

Second, China seeks to diversify supply. With Moscow already one of its top two suppliers (alongside Saudi Arabia), appetite for incremental Russian oil is likely limited.

Finally, Moscow itself is trying to reduce its dependence on mainstream tankers. Shipping from western ports to China requires two-thirds more tanker capacity than to India. And the more tankers Russia needs to keep exports whole, the more exposed it becomes to the risk of price-cap limitations.

To sustain current export levels fully sheltered from the price cap, Moscow would need a fully dedicated, stand-alone, sanction-proof fleet equal in capacity to 637 Aframax tankers…

Russia’s seaborne export levels have remained stable, averaging over 6 million barrels a day of crude and refined products in recent months, despite the fundamental shift in Russian export patterns. Currently, most Russian seaborne oil is transported by mainstream tankers, which are obligated to comply with the price cap. For Moscow to completely avoid exposing any of its exports to price caps, it would need to rely on a stand-alone fleet of sanction-proof tankers. To keep fleet size to a minimum, Moscow would want every tanker in it dedicated exclusively to the Russia trade, with no one working part time for other exporters. At any given moment, a fleet tanker would need to be either laden with Russian oil and outbound to its destination port, or in ballast returning to a Russian port to lift a new cargo (see Figure 10).

To transport Russia’s full export volumes on a sustained basis, free from any price cap restrictions, Moscow would need a fully dedicated, sanction-proof fleet with an estimated capacity equal to 637 Aframax tankers, based on analysis of recent shipping patterns (see Figure 11).13

Currently, Moscow’s active sanction-proof fleet covers less than a third of these needs…leaving a yawning “tanker gap” equal to some 432 Aframax tankers.