Putin’s Looming Tanker Crisis

Will a Kremlin-Engineered Oil Shock be the Next Move in Moscow’s Expanding Energy War?

October 2022

The following essay is a summary of on-going research examining Russian oil under sanctions.

Sanctions will hit Moscow’s seaborne oil exports harder than many expect—and much more than the Kremlin is letting on. Russia’s oil export system will be severely constrained under sanctions since it relies heavily on the physical and financial infrastructure of Ukraine’s allies. This deficiency arises from two things: pipelines to the wrong places and an underdeveloped tanker fleet. Together, they threaten to strand in country up to half Moscow’s export oil—over 3 million barrels a day—once sanctions are fully in place. The price cap mechanism provides a path back to market for Moscow’s stranded barrels by permitting them to access prohibited infrastructure—though at a price.

The Kremlin says it won’t go along with the price cap—and that’s no surprise. With losses on the battlefield and mounting pressure at home, Moscow is increasingly resorting to economic warfare. Its weapon of choice—contrived disruptions of energy supplies. This time it looks intent on engineering an oil shock by holding back its stranded barrels. And as usual, Moscow will try to shift the blame to others, falsely claiming that “price collusion” is “driving supply out of the market.” But the price cap is no buyers’ cartel driving out supply with manipulated prices; any oil Moscow can deliver on its own will trade at negotiated prices, much as it does today. The price cap was created to get oil into the market. Think of it as tolled access to infrastructure that enables otherwise stranded barrels to reach buyers overseas. Moscow’s misdirection is easier to spot when you realize it has a big stranded oil problem brewing—an inconvenient truth it wants to hide from allies and enemies alike.

Marine shipping is a critical link in Russia’s oil export supply chain—and a vulnerable one, too. Six million barrels a day of Russian crude and oil products—around 80% of its total export volumes—must travel by sea to reach markets abroad. The scale of these seaborne operations is immense. On any given day this summer, some 290 oil tankers were engaged in the Russia trade—about 10% of the global long-haul fleet. So great was the need for export shipping tonnage that Russia’s own sizable national fleet carried only one in seven of the country’s seaborne export barrels. The rest were loaded onto vessels owned, financed, and insured by foreign companies—mostly from countries allied with Ukraine.

Soon, as sanctions come into force, those same countries will withdraw their unrivaled marine service businesses from the Russian oil trade. When they do, Russia will struggle to muster anything close to the shipping capacity it needs to maintain recent export levels. A full-blown tanker crisis will likely ensue, one that risks leaving up to half Moscow’s export barrels stranded on Russian shores.

Putin knows Russia’s oil export supply chain is vulnerable to sanctions...

Vladimir Putin is painfully aware of Russia’s deep dependency on foreign shipping and knows an export crisis is looming. This supply chain vulnerability was dramatically exposed in the early days of the war, when foreign shippers, banks and insurers suspended operations at Russian ports. Though the suspension was brief and loadings quickly resumed, the accumulated backlog of stranded oil was so severe, that upstream producers were forced to make an emergency cut of a million barrels a day. The lesson for the Kremlin was clear: Moscow might control supply chain from the wellhead to the waterfront, but once Russian oil is at sea, Westerners are largely at the helm.

This vulnerability is the product of Putin’s own hubris. For years, he has taken for granted that Europe would never spurn Russian oil—that no matter what Moscow might do, ships from Europe would always arrive at Russian ports, ready to load oil bound for Rotterdam, Augusta and beyond. Thus, last Spring, when reports of Russian atrocities in Ukraine turned European opinion in favor of oil sanctions, Putin was caught entirely by surprise, and his complacency quickly gave way to anger and alarm.

Europe’s “erratic” call for sanctions, Putin explained, marked a “tectonic” shift for Russia’s oil industry. “It’s no longer enough for us just to produce oil. We must build out an entire integrated supply chain right down to the end consumer.”

— Vladimir Putin, addressing his oil sanctions task force

…and has convened a task force to find solutions.

Putin hastily convened a task force of senior government officials. Europe’s “erratic” call for sanctions, he explained, marked a “tectonic” shift for Russia’s oil industry. “It’s no longer enough for us just to produce oil. We must build out an entire integrated supply chain right down to the end consumer.” This should include everything from “pipelines and ports” to “trade settlement in local currencies … and insurance services.” And he tasked the assembled officials with fixing this foundational flaw in his fortress Russia strategy.1

Their public posture has been scornful and defiant…

Early on, the leader of the task force, Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak, was scornful of sanctions in his public statements: “If you want to reject Russian energy deliveries, go right ahead. We’re ready for it.” And he was coolly confident in his assertions that Russia’s would overcome all challenges: “We will not be left without a market… we are already creating new transport routes, creating new supply chains, new financial instruments, including settlements in national currencies.”2

“If you want to reject Russian energy deliveries, go right ahead. We’re ready for it.”

— Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak, head of the oil sanctions task force

…but clearly they are struggling with the enormity of the task.

But as the task force got down to work, the immensity of the undertaking became more apparent. For example, in their analysis shipping capacity requirements, they estimated that the national tanker fleet would need to grow fourfold to be able to redirect all Moscow’s export oil to new buyers in Asia. But with shipyard orderbooks full and used tanker markets shallow, such a transformation could take years to accomplish. The task force also busied itself creating spill-liability insurance for foreign shipowners that wouldn’t be subject to sanctions. Such sanction-proof coverage, not widely available today, would be critical to retaining access to foreign tankers. But progress was slow. And that’s not surprising: it’s a highly complex area of insurance involving massive cross-border risk management and complex multilateral agreements.3

By July, Putin had grown frustrated with the task force’s lack of progress. He gathered his officials again and warned them that sanctions “are harming us… and many risks are still out there.” Then he delivered a stinging rebuke for what he saw as their “lax attitude” and “I-don’t-give-a-damn” approach. But no amount of bluster, however, could undo years of complacency. As one senior task force member commented last month with bureaucratic understatement: “It’s clear we’re experiencing problems…it’s not a quick process.” And with sanction deadlines now quickly approaching, some Russian oil companies are bracing for the worst. One small, state-owned producer, allegedly with close ties to the security services, is even including in its contingency planning a scenario that assumes a 100% shut-in of production under sanctions.4

“It’s clear we’re experiencing problems…it’s not a quick process.”

— Minister of Energy

Sanctions will disrupt Russia’s exports in two ways: by sharply increasing its shipping capacity needs…

Once implemented fully, G7-EU sanctions will disrupt Moscow’s marine export system in two ways. First, they will cause a steep rise in Russia’s need for shipping capacity. Sanctions will ban imports of Russian oil into the EU—by far its largest market up to now. Instead, Russia will need to reroute most of these European volumes to non-sanctioning markets, primarily in Asia. But Russia’s oil infrastructure requires over 80% of its seaborne exports to ship out of western ports on the Black Sea and Baltic. This means average voyage times will climb sharply as tankers must sail beyond European waters to more distant Asian ports East of Suez. Longer voyage times mean more tankers are needed just to maintain the same level of daily exports. If Moscow wants to maintain recent export volumes, these longer voyage times, combined with other logistical factors, will increase the tanker capacity it requires under sanctions by approximately 120% compared with June, based on projection in my model of Russian oil exports at risk.

…and causing the supply of foreign shipping capacity available to Russia to collapse.

Russia’s rapidly rising demand for shipping capacity will run headlong into a second disruption caused by sanctions: a precipitous collapse in the supply of foreign tanker capacity available to Moscow. Just as Russia’s shipping needs are doubling, sanctions will likely deny Russia access to over 90% of the global fleet, based on my analysis. This will happen because of a G7-EU ban on certain marine services—including financing and insurance—for any ships exporting Russian oil, regardless of destination. The only exception will be for cargoes sold at a discounted price fixed by the sanctioning alliance—commonly known as the “price cap.”

Many foreign shipowners will be deterred from the Russia trade by the risk of losing vessel financing…

The marine services ban will hit Russia hard because of the outsized role Western finance and insurance play in the oil transport industry. It’s an asset intensive business and relies heavily on leverage to make the economics work. Western banks remain the industry’s leading source of debt financing and normally require borrowers to comply with sanctions as a condition of their loans. This compliance requirement will act as a strong deterrent to any indebted shipowner interested in the Russia trade. Carrying sanctioned oil would violate the terms of their loans and force them to seek refinancing with non-Western lenders—an onerous, costly process fraught with risk.

…and almost all of them by the invalidation of critical spill liability insurance that’s not readily available at scale elsewhere...

An even greater source of deterrence will be marine insurance. Nearly every shipowner in the world today—be they Chinese, Turkish or Norwegian—carries a billion dollars of mandated spill-liability coverage for each tanker they own. Known as P&I (“protection and indemnity”) insurance, it caps shipowners’ spill liability, and is essential for entry at ports around the world and a standard requirement in bank financing.

With thousands of tankers in service, aggregate liability coverage for the industry runs into the trillions of dollars, a sum too large for the traditional insurance markets take on. To manage such extraordinary risk, the industry has created a complex, specialized, cartel-like body, known as the International Group of P&I Clubs or “the IG.” It is a network of not-for-profit, mutual assurance “clubs” made up of the shipowners themselves, whose pooled contributions cover policy payouts. Supplemental cover comes from re-insurance arrangements with many of world’s leading commercial insurers.

Companies from sanctioning countries play a leading role in the International Group, ensuring its observation of sanctions…

G7 and EU businesses play an outsized role in the IG, both at the club level and among the re-insurers. As a result, when these governments impose sanctions, the IG tends to observe them. The prospect of losing P&I coverage is likely to deter the vast majority of shipowners from carrying sanctioned Russian oil. The problem they face is that alternative, sanctions-proof coverage, of comparable quality and scalable to Russia’s needs, simply doesn’t exist today and doesn’t look likely to emerge in the coming weeks.

…along with the 95% of the world’s tanker owners who insure through the IG.

So effective is the IG at meeting the industry’s coverage needs that some 95% of the world’s tanker owners rely on it for their P&I insurance.5 The outliers fall into two categories. First, there are the sanctioned national fleets from major producing countries, like Iran and Russia. Because of the strategic nature of these fleets, their respective governments have arranged ad hoc P&I policies for them backed by state guarantees. It’s far from certain whether such sovereign guarantees will be made available to foreign shipowners. It’s even less certain whether those shipowners would find such sovereign-backed policies attractive: they might not enjoy the strong legal protections in the event of a dispute, and ongoing banking sanctions might put receipt of payouts at risk.

The second category includes a marginal group of aging, anonymously owned, risk-friendly vessels often referred to as the “shadow fleet.” These vessels may carry substandard or even fraudulent P&I coverage from suspect insurers. They also tend to be non-compliant with numerous other mandated industry standards and specialize in transporting sanctioned oil.6

The net effect, then, of the withdrawal Ukraine’s allies from Russia’s oil trade will be a massive squeeze on its capacity to transport oil, with Russia’s capacity needs doubling at the same its access to foreign capacity collapses precipitously.

China is unlikely to provide extraordinary help with either ships or insurance…

But what of Russia’s rapidly expanding customer base among countries not participating in sanctions? Can they provide solutions to Moscow’s tanker troubles? Some observers are quick to assume China will. And at first glance, there’s reason to think that might be so. It’s a leading tanker owner, has deep pockets, and gets some 15% of its imported crude from Russia. Surely it could use its tanker fleet or balance sheet to help an ally. But a closer consideration of the Russia-China energy relationship suggests this is unlikely to happen. Of the various interested parties in China—insurers, shipowners, refiners, and the state—none appears to have a sufficiently compelling reason to push for extraordinary measures to help Russia out. Indeed, some will directly benefit from a tanker crisis in Russia. Let’s consider each in turn.

…as neither insurers, shipowners, refiners, nor the state have much to gain by it...

China’s marine insurers rely on co-insurance arrangements with the International Group to cover Chinese vessels. China’s leading P&I insurer is believed by some to be next in line for full membership in the International Group.7 Chinese insurers have resisted past calls by shipowners to write P&I coverage for sanctioned Iranian oil, since such coverage wouldn’t be backed by their co-insurance arrangements with the IG. As one Chinese industry official explained: “We are talking about $1 billion (per tanker). No single insurance company can handle that.” Instead, China has opted to rely on Iranian and shadow fleet vessels to transport US-sanctioned Iranian oil to China.8

“We are talking about $1 billion (per tanker). No single insurance company can handle that.”

— Chinese marine insurance industry official

…mostly owing to the peculiar logistics of the Russia-China oil trade and the structural incompatibility of China’s tanker fleet.

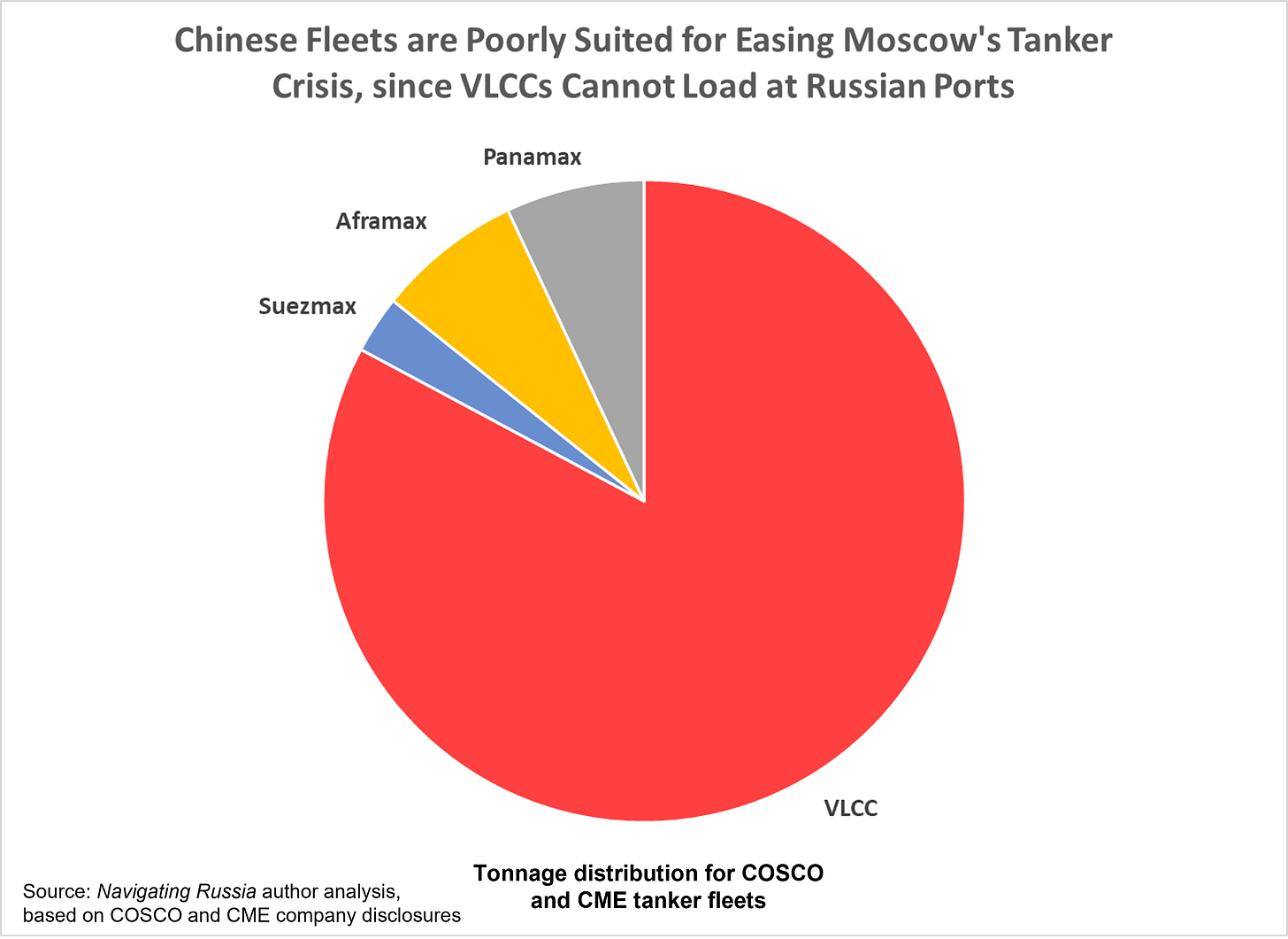

As for China’s major commercial fleets, they are barely active in today’s Russian oil trade. In June, for example, less than 1.5% of the tonnage of China’s two dominant tanker fleets—COSCO and CME—was engaged with in the Russia trade.9 And that is unlikely to change, because their fleet composition is structurally unsuitable for the Russia trade. Some 80% of their tanker tonnage consists of VLCCs (“very large crude carrier”). These are the largest class of tanker commonly in service today but are physically too large to load at Russian oil sea terminals, owing to navigational chokepoints and other factors. As for the remaining 20% of their tonnage, it would likely make a difference only on the margins for Russia.

China’s VLCC-heavy fleet was developed with the Persian Gulf trade in mind. That’s why Chinese shipowners pushed to be allowed to remain in the Iran trade, once it was sanctioned. Their efforts, however, were unsuccessful. The Russia trade is far less attractive for them, so it’s hard to imagine they’ll be pushing any harder—or have any more success—to stay in the Russia trade.

China’s independent refiners may even gain substantial pricing leverage from Russia’s scarcity of shipping capacity.

Next come China’s savvy independent refiners, who may even quietly welcome Russia’s shipping woes. Once sanctions are in place, they will be far closer to Russia’s Pacific ports than any other major buyers. Russian voyage times to the next closest major market are three times as long. Three times the journey means three times the tankers needed just to deliver the same daily volumes. If Russia is rationing tanker capacity, this gives Chinese traders extraordinary pricing leverage. A senior Russian oil executive and seasoned China negotiator observed with dread: “they will bring us to or knees as soon as they become the only buyers.”10

“they will bring us to or knees as soon as they become the only buyers.”

—veteran Russian oil executive and seasoned China negotiator

Finally, there is the Chinese government itself. Sanctions pose little risk to most of Beijing’s current import volumes from Russia. Almost all China’s current imports come either overland by pipe, or from Russia’s nearby Pacific ports. Average Pacific port voyage times to Chinese ports are shorter than to any other major market open to Russia under sanctions. If you were rationing scarce tanker capacity and trying to maximize daily export volumes, Pacific deliveries to China would be the first place you would allocate capacity. And Russia’s fleet can easily cover these Pacific exports to China on its own.

Any incremental imports of size would need to be shipped from Russia’s distant western ports—a very inefficient use of China’s structurally incompatible fleet.

If, however, Beijing wanted to significantly increase imports from Russia, it would require extraordinary amounts of additional tanker capacity. The reason is the peculiar logistics of the Russia-China oil trade. Most of China’s current imports come via the East Siberian-Pacific Ocean pipeline, which is now at capacity. And additional volumes would need to come from Russia’s distant Western ports on the Black Sea and the Baltic—none of which can load VLCCs. Attempting to use China’s ill-suited fleet would make for a highly inefficient use of tonnage.

If, for example, China wanted to add an additional 10% of Russian crude to its import mix, it would need to allocate to the Russia trade on a full-time basis some 70% of the tonnage of China’s two dominant tanker fleets, by my calculations.11 And since those vessels would all lose their IG P&I coverage, Beijing would also need to make up for tens of billions of dollars of lost liability coverage. Beijing may deem this an imprudent use of both strategic shipping assets and sovereign credit, regardless of the discount it might be able to demand. If additional cheap Russian oil is what China seeks, it could get that through the price cap mechanism and save its fleet and balance sheet for better uses.

India, with a much smaller fleet and little marine P&I, is also unlikely to provide solutions for Russia’s shipping capacity shortfall.

India, likewise, is unlikely to shore up Moscow’s supply-chain weaknesses. Its marine P&I industry is only in its infancy. Its commercial tanker fleet is far smaller than China’s and it relies on foreign vessels for most of its imports. Moreover, the shipping capacity needed to keep recent export volumes flat to India would be three times that required for China, because of the greater distances from Russian sea terminals (India is currently supplied mostly from Russia’s Western ports, China out of the Pacific). It’s hard to see how India can be of much help to Russia with either insurance or boats.12

Capacity will come mostly from Russia’s national fleet and the risk-friendly “shadow fleet,” but still fall well short of Russia’s needs…

Russia will likely end up relying on two sources for shipping capacity under sanctions: 1) its own national fleet, Sovcomflot (SCF), and 2) the so-called “shadow fleet.” The latter is a marginal group of aging tankers with anonymous ownership and an appetite for transporting sanctioned crude. Russia’s own fleet could offtake up to 25% of recent seaborne volumes, if deliveries to the closest open markets were prioritized, based on my estimates. The shadow fleet is substantially larger than SCF, though estimates of its size vary. Like China’s fleet, however, the shadow fleet, too, is top heavy with VLCCs that cannot load at Russian ports. For this and other reasons, the gross tonnage of the shadow fleet must be substantially discounted when estimating how much effective shipping capacity it could provide to Russia.

…making possible a drop in export volumes of up to 3.3 – 3.9 million barrels per day, absent any capped price sales, once sanctions are fully in force...

Together, the capacities of SCF and the shadow fleet will fall far short of what Russia will require under sanctions to maintain recent export levels, based on my projections. The impact of this constrained shipping capacity on export volumes will be substantial, leaving a large portion of Russian exports stranded in country. Once sanctions are fully in place, Russia’s total crude and product exports (seaborne + land) could fall by as much as 3.3 to 3.9 million barrels a day from a baseline of 7.5 million barrels a day, absent any sales under the price cap mechanism or revisions in the planned G7-EU sanctions. This decline is likely to phase in gradually from October through the end of January, as foreign shippers start avoiding cargoes that might not reach their destination ports prior to the December 5th and February 5th cutoff dates.

…and cuts in deliveries to more distant markets, like India, as tanker capacity rationing is introduced.

Such a decline would have a major impact on oil markets. It would also have implications for specific importers of Russian oil. Absent capped price sales, Moscow would need to ration scarce tanker capacity. If it rations these with the aim of maximizing volumes, it will likely decide to cut deliveries to more distant overseas markets, like India, while prioritizing closer-in markets, like China and Turkey.

The market consensus appears more optimistic about the resilience of Russia’s export supply chain than the view expressed here.

Many market observers expect declines in Russian exports, but not generally of the magnitude given here. They tend to see Russia’s supply chain as being more resilient than my analysis would indicate. Some believe shipowners wishing to continue in the Russia trade will find alternative sources of P&I insurance. Others think Russia’s surreptitious purchases of used tankers could bridge the gap. Still others point to various subterfuge shipping schemes—already being tested—that might be used in smuggling operations.

…but Russia’s various anti-sanction schemes may lack sufficient speed and scalability—the scale of Russia’s export requirements is immense; they will likely only help around the margins.

All these observations have merit and highlight measures Russia is trying to develop to lessen the impact of sanctions. And no doubt some of these anti-sanction measures will succeed…but only within certain limits. What they all face the is the challenge of scalability: can they be quickly scaled up to a magnitude that will fundamentally change outcomes for Russia? When it comes to Russia’s massive oil exports needs, the importance of scale cannot be overstated.

Providing credible, sanctions-proof P&I coverage on the scale Russia needs would involve complex, multi-lateral agreements involving cross-border asset pooling and risk-sharing on a very large scale—and all quickly papered up by legal advisors. That’s a heavy lift.

Take, for example, marine insurance. To transform outcomes for Russia, it wouldn’t be enough to arrange sanction-proof “spot” P&I coverage for, say, 30 or 40 ships that occasionally lift sanctioned Russian crude and need a one-off coverage of those cargoes when they do. To be transformational requires much more. To reduce Russia’s projected export decline to, say, 1 million barrels a day would require on the order of an additional 200 vessels from the licit fleet going into the sanctioned Russian oil trade on a full-time basis, by my estimates. That, in turn, would require $200 billion of acceptable, sanctions-proof P&I cover to replace their invalidated IG policies. Can enough well-capitalized parties, with expertise in marine insurance and not subject to sanctions, be engaged to write two-hundred billion dollars of P&I policies by the end of the year for shipowners from around the world? Perhaps, but it feels like a stretch.

Buying up tankers in the second-hand market and clandestine smuggling operations also face practical challenges of scalability.

Or consider the threshold test for Russia’s tanker acquisition program. Can Russia realistically hope to finance and purchase the equivalent of 12% of the global Aframax and Suezmax fleet over the next two months? And where would prices in the resale market go as the acquisition campaign rolled out? Or consider what is required to scale up ship-to-ship (STS) transfers for smuggling operations at scale. With tanker capacity being rationed, would Russia have nearly enough vessels to conduct the many inefficient, capacity-intensive STS transfers needed to smuggle, say, two-million barrels a day into Europe? And wouldn’t an operation that big also be easy to spot and interdict?

Those are the kinds of threshold tests that a transformational anti-sanctions solution would need to meet. It’s not inconceivable that one or more could be met, but it seems unlikely, especially in such a short time frame.13

Oil sanctions pose an ethical dilemma: withdrawing from Russia’s blood-oil trade could lead to widespread economic hardship.

Oil export revenues are Moscow’s most important source of funding for its brutal war against Ukraine. It was moral outrage over this brutality that led Ukraine’s allies to ban imports of Russian oil and prohibit businesses from engaging in this lucrative trade. But because of Russia’s weak supply chain, an oil supply shock could ensue under sanctions that would cause widespread economic hardship.

The price cap addresses this dilemma by striking a balance between two competing goods. It allows otherwise stranded Russian oil to reach markets using the export infrastructure of Ukraine’s allies…

The price cap is designed to address the dilemma of oil sanctions (here I should be clear that by “designed” I speak of function, not intent; the price cap was developed and implemented by others, and I cannot speak with authority to their intent; what I describe here is how I believe the price cap as structured will likely function).14 It creates a pathway to market for stranded export barrels that Russia is incapable of delivering on its own. It does this by allowing those stranded barrels to be shipped via the physical and financial infrastructure of Ukraine’s allies.

…while also limiting excess profits on those sales.

As often with infrastructure, there is a toll. In this case, it takes the form of a cap on the price Moscow can receive for its otherwise stranded barrels. And that capped price is set with the aim of limiting excess profits.

The price cap will have little direct impact on barrels Russia can export on its own—nor is it designed to.

But what of those barrels that Russia can deliver to markets on its own, without help from Ukraine’s allies? How will the price cap affect them? The price cap is not designed to control the pricing of these “non-stranded” barrels. It does not create some form of buyers’ cartel trying to impose off-market pricing on supplies already in the market. The global oil markets are too broad and efficient to sustain large-scale, cross-border collusion among buyers. For any barrels Moscow can deliver to customers on its own, it will be free to negotiate prices in the market.

For the price cap to be effective, Moscow must choose to sell its stranded oil, which now looks increasingly unlikely.

For the price cap to work, however, Moscow must choose to produce and sell its stranded export barrels. That was never a forgone conclusion (as I wrote last April), and now appears even less likely…at least in the near term.15

Moscow is waging an economic war that aims to cause hardship through disrupting commodity supplies…

Moscow is waging hybrid warfare against Ukraine and its allies. In addition to its kinetic attacks on Ukrainian soldiers and civilians alike, it is waging an economic war that targets not only Ukraine and its allies, but the entire international community. Moscow’s weapon of choice is the engineered disruption of commodity exports—its own and Ukraine’s. Gas and grain are just two recent examples.

The aim of Moscow’s commodity disruption stratagem is to erode international support for Ukraine. It does this in two ways—one obvious, the other less so. The obvious way is by inflicting indiscriminate economic hardship through higher prices and shortages of basic goods like food and energy.

…and stoking social divisions with false narratives.

The less obvious way is by stoking social divisions within countries backing sanctions. It does this by spinning false narratives that shift blame for supply disruptions onto western political leaders, while denying Moscow’s primary agency. This cut-and-blame tactic was on full display when Moscow throttled gas supplies to Europe and disingenuously claimed technology sanctions were at fault.

Moscow now looks intent on expanding this economic war by causing an oil supply shock...

With recent setbacks on the battlefield and growing pressure at home, the Kremlin now looks intent on expanding its economic war—this time by engineering an oil supply shock. It is already deploying a false narrative aimed at shifting the blame. It goes like this: Russia stands capable and ready to keep supplying markets with our oil. But Western politicians seek to weaken Russian through a buyers’ cartel that imposes non-market prices on our freely traded oil. As anyone knows, when you artificially depress prices, it drives out supply. So, if there’s a supply shortage—blame the price cap.

…and then disingenuously blaming it on the price cap.

As with all Kremlin gaslighting, it is artfully crafted around half-truths and misdirection. Here, Moscow starts with the false claim that it will be capable of delivering its oil to the market. But that’s not true for the large portion of oil that is likely to be stranded. Moscow then claims that the price cap will drive this supply out of the market through manipulated pricing. And here we see the sleight-of-hand. The price cap doesn’t drive supply out of the market—since the volumes it affects aren’t even in the market in the first place—they’re stranded in Russia. The price cap does just the opposite—it enables those stranded volumes to get into the market by providing access to infrastructure.

Were Moscow actually capable of getting those volumes to market on its own, it would do so and then sell them at negotiated prices—much as it does today. There would be no price cap, because there wouldn’t be any need for one. It only exists because Moscow can’t move all its oil on its own—it’s dependent on help from Ukraine’s allies.

To sum up, the price cap is not a buyers’ cartel for managing prices on oil that’s already in the market; it’s tolled access to infrastructure for delivering stranded oil to the market. But to grasp this, it helps to be aware of Russia’s stranded oil problem—an inconvenient truth Moscow wishes to hide from allies and enemies alike. Beware Moscow’s misdirection.

Alternative scenarios could still play out.

A Kremlin-engineered supply shock appears at this point quite likely, but not yet inevitable. There are alternative scenarios that could still play out. If, for example, Iran sanctions are dropped, Moscow may be able to secure additional tanker capacity from the shadow fleet. Indeed, the shadow fleet could end up expanding significantly in response to demand from Russia. And as Iran’s large inventories in storage get released into the market, this could blunt the impact of an oil shock. Moscow might then prefer to up its sales volumes.

And sales through the price cap cannot be entirely written off. It would be very characteristic of the Kremlin to quietly test the integrity of the price cap mechanism early on by allowing a few cargoes to be sold through it. They would seek out vulnerabilities in compliance and monitoring systems that could be exploited to Moscow’s benefit. If the opportunities for exploitation appeared sufficiently attractive, Moscow might scale up sales through price cap regime.

Finally, if oil prices slump and Moscow is pressed for cash, it might increasingly avail itself of the price cap simply because it needs the money.

A supply shock—if it comes—will inflict hardship on the international community, roil the markets and test the resolve of Ukraine’s allies. If their resolve holds and prices settle, Moscow would emerge a much diminished force: banished from its largest market, awash in stranded hydrocarbons, beset by decaying production systems, and starved of vital export revenues.

This essay is a summary of on-going research examining Russian oil under sanctions.

The quantitative analysis in this essay is based on a bottom-up model of Russia’s oil export infrastructure and the evolving patterns of Russia’s seaborne oil trade. The model’s data sets include empirical observations of some 1,500 loadings at Russian ports in recent months and the tracking of voyage data, based on data feeds from a commercial, third-party marine tracking service. Unavoidably, some of the analysis relies on my subjective judgements. These are informed by familiarity with Russian-language industry source materials, a twenty-five-year career in the global financial markets, more than a decade of living and working in Russia, thousands of hours of discussions with engineers and executives from the Russian energy industry, and first-hand exposure to a number of its leading figures.

14 April 2022 meeting: http://static.kremlin.ru/media/events/video/ru/video_low/Yw3gDJuyc9QE5kvWVfEElcCrevbCx0RA.mp4

17 May 2022 meeting: http://static.kremlin.ru/media/events/video/ru/video_low/HIfQY7a405xAGKtsTXzUI9hLNeCSWlfF.mp4

Government.ru, 17 June 2022; Tass, 5 September 2022.

8 July 2022 meeting: http://static.kremlin.ru/media/events/video/ru/video_low/IjKMmBeo9M3V8Ib6ICbNsTRE1slie5fu.mp4

Neftegaz.ru, 12 October 2022; Tass, 5 September 2022; Financial Times, 22 May 2022.

Assuranceforeningen Gard. The rate of IG P&I coverage among foreign tankers loading in Russia this June was even higher, at 97%.

TradeWinds, 11 May 2022; Lloyd’s List, 12 April 2022.

TradeWinds, 27 May 2022.

Navigating Russia author estimates, based on COSCO and CME company disclosures and tanker tracking data.

The route would require a large flotilla of Suezmax and Aframax tankers shuttling out of the Baltic or Black Sea to waiting VLCCs for ship-to-ship transfers and long onward voyages around the Cape of Good Hope. Pilot tests of this delivery route have shown exceedingly slow voyage times, owing to long delays from poorly synched STS rendezvous schedules.

India did help Russia out in June when its national shipping classification society stepped in to vouch for the safety compliance of Sovcomflot, Russia’s national fleet. Previously, those vessels had been certified by Russia’s own national classification society, but its certification authorities were stripped by the international governing body of classification, the IACS, shortly after the Ukraine invasion. Reuters, 23 June 2022.

For those interested learning more about tankers and sanctions, I highly recommend the excellent investigative work done by the teams at Lloyd’s List and Tankertrackers.com. And for analysis on seaborne flows out of Russia, the superb on-going coverage by Julian Lee and his team at Bloomberg is hard to beat.

Last spring, I wrote proposing a structure for Russian oil sanctions that was fundamentally different from what is now enacted. The plan I described (along with numerous European economist) would allow for continued sales into all sanctioning countries at negotiated market prices, but include a floating tariff structure that would tax the windfall component of revenues and then use those proceeds to fund Ukrainian relief. What the enacted EU-G7 policy does is prohibit sales to sanctioning countries altogether and impose a non-market, capped price on any sales to non-sanctioning countries that make use of financial or physical infrastructure (mostly insurance & tankers) provided by Ukraine’s allies. See Russian Oil’s Achilles Heel.

Shadow fleet is much larger than we think, around 150 vessels (mostly Afras) could be deployed for the Russian trade. The economics are certainly there

Excellent analysis. One small point regarding your scenarios at the end. If anything, oil sanctions against Iran are likely to tighten, not slacken, due to Iran’s supplying Russia with kamikaze attack drones and Iran’s training Russian military personnel in how to use them effectively against Ukraine.