Russia's Hidden War Debt (full report)

Moscow has been discreetly funding heavy war costs with risky, off-budget debt. But the scheme has caused major problems—with more likely to follow—offering useful leverage to Ukraine and its allies.

Working Draft

This report identifies a new dimension of Russia’s war-funding strategy: a heavy reliance on off-budget debt to supplement its defense budget allocations. Excessive reliance on this off-budget funding strategy has elevated Russia’s systemic credit risk to a point that it is constraining the Kremlin’s war finances and could weigh on it war calculus.

Summary

Moscow has been stealthily pursuing a dual-track strategy to fund its mounting war costs. One track consists of Russia’s highly scrutinized defense budget, which analysts have routinely deemed “surprisingly resilient.” The second track—largely overlooked until now—consists of a low-profile, off-budget financing scheme that appears to make up a major portion of Russia’s overall war expenditures. Under legislation enacted in February 2022, the state has taken control of war-related lending at Russia’s major banks. It is directing them to extend preferential loans—on terms set by the state—to a wide range of businesses providing goods and services for the war. Since mid-2022, this state-directed war-funding scheme has helped drive a large part of Russia’s anomalous ₽36.6 trn ($446 bln) surge in overall corporate borrowing.

Initially, this off-budget war-funding scheme proved advantageous to Moscow by helping limit defense spending in the budget to levels that are easily managed. That misled budget-watchers into concluding—incorrectly as it turns out—that Moscow faces no serious risks to its ability to sustain funding for its war on Ukraine. More recently, however, Moscow’s heavy reliance on state-directed preferential lending has begun to cause serious, adverse consequences at home. It has become the main driver of Russia’s 10% inflation and has sent the Central Bank’s key rate to a record 21%.

More broadly, Russia’s off-budget war debt is significantly elevating systemic credit risk, both for the near- and medium-term. High interest rates are driving up corporate distress levels in the “real” economy and raising fears of widespread bankruptcies. The Central Bank has voiced concern over “aggressive” lending and inadequate capital buffers in the banking industry. What’s more, the state has now saddled the banks with large amounts of problematic, corporate war loans. Many could turn toxic once the shooting stops and defense contracts get cancelled. Worse still, relaxed oversight rules on defense-related loans mean bank regulators might not see these problems arising until it’s too late.

By late 2024, the Kremlin had been briefed on these rising risks and warned that change is needed. This poses a dilemma for Putin: continue relying on off-budget debt, and you further increase the risk of cascading credit events that undermine Russia’s image of “surprising resilience” and weaken its negotiating leverage. The alternatives: a major increase in the budget deficit—with the bad optics that entails—or a sharp reduction in spending on the war. This may explain Putin’s recent complaint to his generals that they can’t “keep pumping up spending to infinity.”

These new developments are likely to affect Moscow’s war calculus in two ways:

Moscow will be less inclined to believe time is on its side—the longer it must fund elevated war costs, the greater the risk of escalating credit events;

Moscow will prioritize sanctions relief aimed at boosting cashflows to help with politically perilous post-war debt restructuring and rearmament. Concessions that would provide the greatest cashflow relief include (i) an easing of oil sanctions, (ii) the resumption of pipeline gas deliveries to Europe and (iii) the unfreezing of Russia’s wealth fund.

Given Russia’s financial challenges, maintaining these constraints on Russia’s cashflows insures Ukraine and its allies retain substantial leverage. If kept in place past a ceasefire, they could be instrumental in securing a final, comprehensive peace settlement—including reparations.

About the author

The author worked for many years as an investment banker at Morgan Stanley and Bank of America Merrill Lynch, where he was a vice chairman. During his banking career, he advised companies and governments around the world and led numerous financings, including Russia’s largest ever corporate transaction. He received an undergraduate degree in Russian studies and a doctorate in Russian and Middle Eastern history from Harvard and a masters in Middle Eastern languages from Oxford, where he was a Rhodes Scholar. Currently, he conducts research on Russia’s energy economy at Harvard’s Davis Center and is writing a history of the Russian oil industry and its impact on civil society. He also is the author of the Substack Navigating Russia.

Table of Contents

Introduction: In Search of Russia’s War Debt

Chapter 1: Russia’s Anomalous Corporate Credit Surge

Chapter 2: The Relentless Driver of the Credit Surge—State-Directed, Preferential Bank Loans

Chapter 3: How the Kremlin Seized Control of Defense-Related Bank Lending

Chapter 4: How Big is Russia’s Off-Budget War Debt? A Broad Estimate

Chapter 6: A New Threat on the Kremlin’s Radar—Credit Event Risk

Conclusion: Bonfire of the Cashflows

Appendix 1: Credit Surge Raw Data

Appendix 2: Russia’s Evolving Business of War. Identifying War-related OKVED2 Industrial Sectors

Introduction: In Search of Russia’s War Debt

“We have no limits whatsoever on financing. The country and the government will provide everything the army asks for, everything.”

—Vladimir Putin addressing the Ministry of Defense, December 21, 20221

“We cannot keep pumping up [defense] expenditures to infinity, increasing them without limit.”

—Vladimir Putin addressing the Ministry of Defense, December 16, 20242

Where is Russia’s war debt? Burdened by sanctions and showing only modest revenue growth, how is the Russian state paying for Europe’s largest war in 75 years while borrowing so little?

Where is Russia’s war debt? That is one of the puzzles of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Large wars normally go hand in glove with heavy state borrowing. Indeed, Western banking arose in part to help states pay for increasingly expensive wars.

And yet, Russia—despite waging Europe’s largest war in 75 years—appears to be paying nearly all its war costs out of pocket, from current tax revenues. At least that’s the impression one gets on initial inspection of the numbers. Federal budget deficits have been remarkably modest—under 2% of GDP in 2023 and 2024. So too has the state borrowing used to cover them. At the same time, Moscow’s budget revenues have grown very little in real terms since 2021. And sanctions have denied Russia access to most of its sovereign savings.

So, how, then, is Moscow covering the extraordinary costs of what looks to be a very expensive war? Where is the money coming from? Even the Soviet Union imposed war bonds on the public. Where are Russia’s “Special Military Operation” bonds?

Western analysis of Russia’s war finances often focuses too narrowly on the federal budget, overlooking a large “off-budget” component in Russia’s war-funding strategy.

Close observers of Russia’s budget will be quick to respond that the defense part of the budget has been growing much faster than the budget itself, thus boosting funding for the war. That observation is undeniably true. But it also illustrates a methodological problem in how we have been analyzing Russia’s war finances. We have been laboring under the assumption that the Kremlin runs all revenues and costs for the war through the federal budget. Consequently, all matters are viewed through the lens of the budget, and all questions are answered with reference to the budget. For example, when we ask “where is Russia’s war debt?” the answer comes back “there’s no substantial new debt in the budget, so it must not exist.”

But is it reasonable to limit ourselves to the budget when assessing Russia’s war finances? After all, any IMF official3 or scholar of state capitalism4 will tell you, the boundary between public finances and private markets is often blurred. Almost every state transgresses this boundary from time to time to direct private capital towards political priorities. Some, however, do it more frequently than others.

Examining relevant financial evidence outside the budget changes our picture of Russia’s war funding strategy and the risks around it.

Why should we think Russia—no stranger to transgressing boundaries—is any different? Why should we assume the Putin regime—facing its most costly and risk laden crisis ever—is scrupulously observing the boundary between Russia’s budget finances and the private capital markets? Perhaps it’s time to set aside these presuppositions and look at the relevant data with fresh eyes.

That is what this report aims to do: to take a fresh look at Russia’s war-funding strategy by broadening the scope of analysis beyond the budget. And once we do that, we begin find data and other evidence showing that Russia’s elusive war debt does, in fact, exist. Indeed, it appears to be quite substantial. It’s simply not sitting on the government’s balance sheet, where you’d normally look for it. Instead, it’s somewhere unexpected, lightly camouflaged, but otherwise hiding in plain sight.

The three key conclusions of this report

Based on analysis of this extra-budgetary data and evidence, this report draws three key conclusions:

1) the Russian state has been drawing discreetly but heavily on financial resources from outside the budget to fund its war effort; this “off-budget” funding strategy is a material part of its overall war-funding strategy;

2) Moscow’s off-budget strategy suffers from serious structural flaws; its overuse has elevated systemic risks in the economy, especially credit event risk;

3) By Q4 2024, senior figures in Moscow had begun recognizing the risks posed by their off-budget funding strategy; they now face a funding dilemma that could weigh on their war calculus.

The Kremlin’s strategy for dealing with the cash crisis at Gazprom offers insights into its off-budget strategy for funding its war costs: raise cash by borrowing in the corporate debt markets.

A confession. When I first stumbled across evidence of Russia’s missing war debt, it was quite by accident. I was investigating a different, but related, debt puzzle: how the Kremlin was dealing with the dual funding crises it had inflicted on Gazprom, its largest taxpayer.

After the Kremlin crippled Gazprom’s core business—exports to Europe—the company’s once mighty gas division was hemorrhaging cash. Those losses, in turn, threatened to trigger a debt service crisis. Gazprom is one of the world’s largest corporate borrowers. At the end of 2023, it was laboring under an estimated gross debt of some $80 billion, based on its IFRS accounts. With most of its European revenues gone and its domestic business apparently losing money, how would Gazprom manage its towering debt load?

As Russia’s most strategically important company, Gazprom’s cash problems were not only a challenge for management, but for the government as well, which owns a controlling stake in the business. My question was: how would the state respond to this funding crisis? Would it liberalize domestic gas prices? No—that’s way too inflationary and risked social unrest. Would it cut the gas giant’s taxes? No—the federal budget was already running a deficit.

Instead, the government’s solution was more radical: have Gazprom do something that’s rarely advisable for a debt-laden company with a structural cashflow deficit—borrow more money. And that’s exactly what the company did—and at record high interest rates. Since late 2022, the group has issued nearly 40 separate ruble bonds in Russia’s local markets raising ₽1.4 trillion ($15.8 bn). By late 2024, its borrowing costs had topped an eyewatering 22%. By comparison, as recently as November 2021, Gazprom had borrowed in the London markets with a razor thin coupon of just 1.85%.

The state is pragmatically, but recklessly, using Russia’s credit markets to channel money quickly where it’s needed, but with little apparent regard to how that debt gets repaid.

Gazprom’s slow-motion cashflow trainwreck is still playing out. But that’s a story for another day.

It does, however, bear on this report in two important ways. First, it reveals one of the strategies the Kremlin is using to address emergency funding needs in the teeth of a crisis. If a company needs funding quickly, as Gazprom did, the state has the company raise that cash in the corporate credit markets. For a sophisticated borrower like Gazprom, that can be done through the bond market. But it can also be done through Russia’s much larger corporate bank loan markets as well.

When you think about it, that’s a pragmatic funding strategy for the state: the corporate credit markets are Russia’s deepest, most liquid pools of readily investable capital. Money can be raised fast and at scale. And the government doesn’t have to mess around with adjustments to the federal budget or amendments to the tax code. If a strategically important company like Gazprom is short on cash, just find someone who will lend it to them.

But this can be a reckless strategy, too. Especially if it prioritizes political expedience over commercial concerns like the borrower’s credit quality and liquidity profile. Bank credit committees and regulators are there to reduce the risk of imprudent lending. Politically directed lending, however, often dispenses with these safeguards.

Russian markets keep lending heavily to a troubled Gazprom—₽1.4 trillion ($15.8 bn) and counting—because they see it as “too big to fail.” It’s just thinly veiled government debt.

Based solely on Gazprom’s deteriorating credit statistics, a sober credit committee might think twice before lending to the cash strapped company. But for special companies like Gazprom, creditworthiness isn’t just the sum of its cashflows—intangible factors also come into play. As Russia’s most strategically important company and a quasi-sovereign borrower, it’s the quintessence of “too big to fail.” And that’s pretty much what the Russian credit rating agencies have been saying in their reports when explaining their AAA rating for Gazprom’s ruble bond: ignore the company’s fundamentals—the state will never let this company go under.5 And this explains why the markets keep taking up new Gazprom issuances: in their eyes, it’s just thinly veiled government debt.

The state, in effect, is imposing losses at Gazprom by making it to supply the Russian market at deeply discounted prices, and then having the company cover those losses borrow heavily in the market. Meanwhile, the market is willing to lend because it believes the state will bail out Gazprom if it gets into trouble.

In the short term, that’s a nice outcome for the government. It spares the government the burden of having to raise debt or taxes to subsidize Russian gas prices. So, to all outward appearance, the state appears unfazed by the steep decline of its one-time national champion. In reality, there’s plenty of lending happening against the state’s credit; we just don’t see it, because it’s all on Gazprom’s balance sheet. But sooner or later there will be a reckoning—Gazprom can’t finance losses with debt forever. And when that happens, the state (and the taxpayers) will have to pay the bill—unless, of course, large-scale sales to Europe resume…

It’s not just Gazprom borrowing aggressively. There’s been an anomalous and large 71% surge in corporate debt since mid-2022, up ₽36.6 trn ($446 bn)…

So, the situation at Gazprom reveals how the state is using the corporate credit markets to address funding crises by having them lend money directly to the companies that need it. And for a sophisticated, too-big-to-fail company like Gazprom, that’s not a huge surprise; it’s a pragmatic stop-gap solution, especially if you think you can scare Europe into resuming Russian gas purchases with hollow threats of sending it all to China.

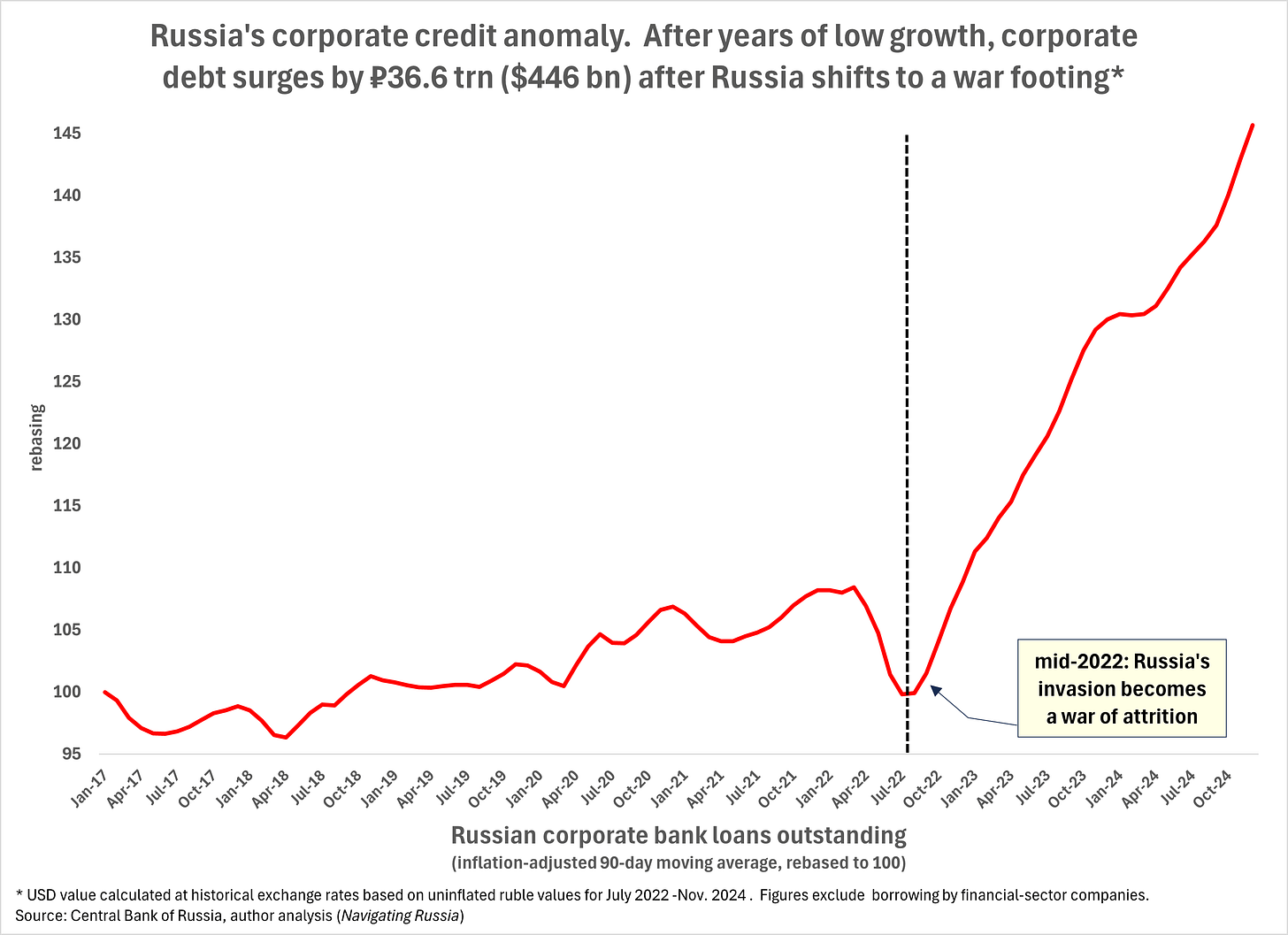

What did come as a surprise, however, was the second thing I came across in my Gazprom research. It turns out that Gazprom isn’t the only Russian company borrowing with abandon. When you dusted off the Central Bank’s much neglected data set on Russian corporate borrowing, something quite remarkable and unexpected appeared: a perfect hockey stick—a long flat trendline that suddenly inflects upward (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

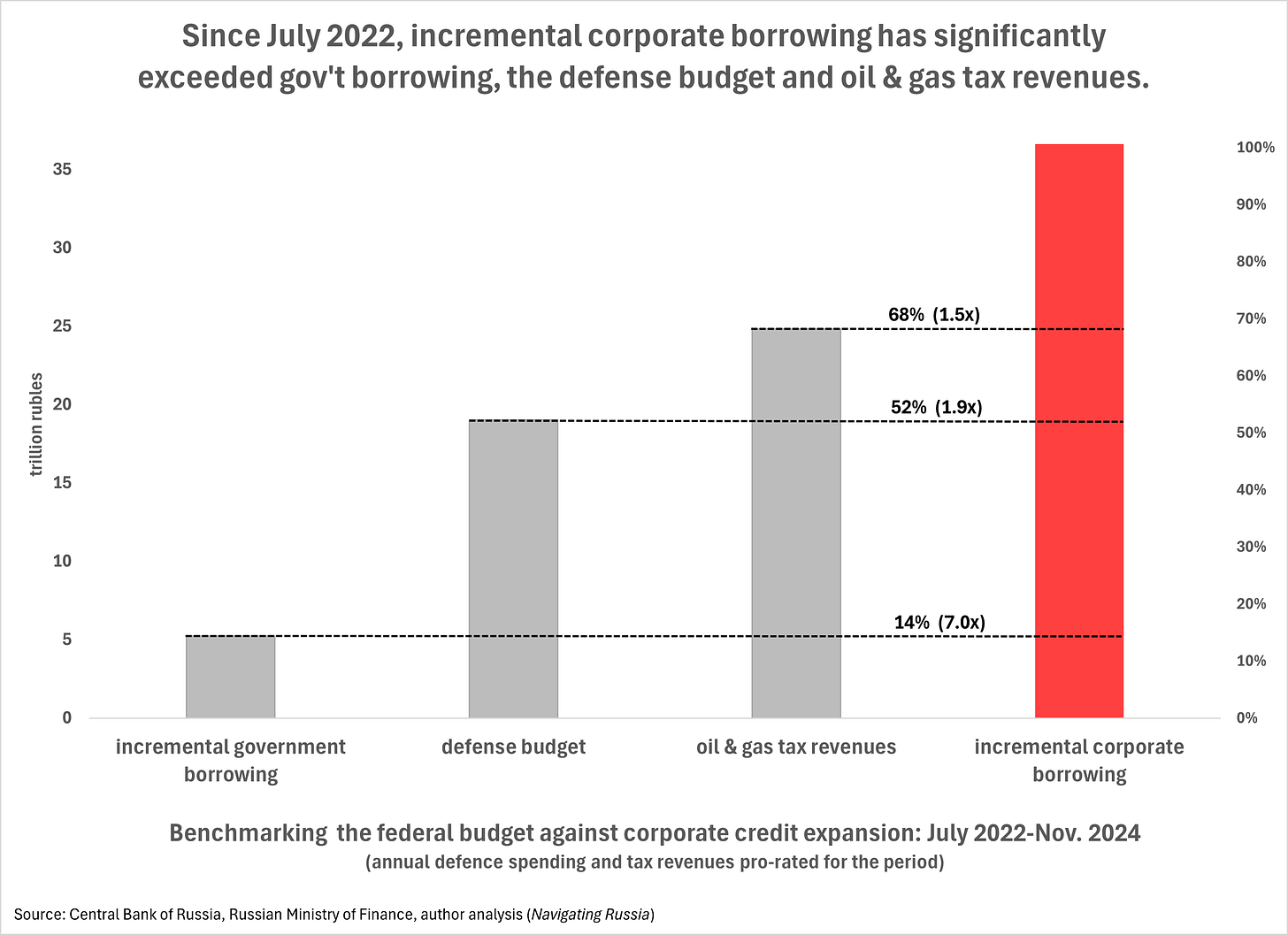

…its scale is very large. It dwarfs key budget metrics, like oil and gas revenues, the defense budget or incremental government borrowing…

After years of low growth, in mid-2022, Russian companies suddenly began borrowing aggressively. The scale of incremental corporate borrowing was immense: ₽36.6 trn ($446 bn) from July 2022 through November 2024 (see Appendix 1).6

That’s 1.9 times the size of the defense budget for the same period, 7 times what the state had borrowed and 21.3% of 2023 GDP (see Figure 2). And it perfectly coincided with Russia’s partial shift to war footing.

Figure 2

…and the sectors taking on new debt the fastest are those providing goods and services for the war—2.7 times faster than non-war-related sectors

Moreover, closer examination of the data revealed the borrowing was highly concentrated in industry sectors providing the goods and services you would need to wage a large-scale land war. These war-related sectors consist of 4 core arms manufacturing sectors and 11 additional sectors providing essential goods and services required by the state for the war (see Appendix 2). Debt growth rates for these two war-related sectoral groups have tracked very closely with one another (see Figure 3). And since mid-2022, they have sharply outpaced debt growth in Russia’s 63 non-war-related industry sectors.

Figure 3

If this is Russia’s elusive war debt, why has the state chosen to impose it on companies providing war-related goods and services to the state, where credit quality has been notoriously poor?

So, was this it? Had I stumbled across Russia’s elusive war debt?

But it didn’t make sense. Why would you load up a lot of corporate balance sheets with war debt? Russia’s core arms manufacturers are nothing like the sophisticated, once-cash-rich Gazprom. They are notoriously bad credits, living hand-to-mouth off underpriced government contracts and perpetually on the brink of insolvency. As for the legion of new companies enlisted into war effort, they might be more efficient businesses, but their wartime contracts would dry up as soon as the shooting stopped. Why would banks take on so much risk? How are they going to get repaid? Not all these borrowers are too big to fail. How could bank credit committees sign off on such madness?

Since 2011, the state has orchestrated off-budget bank loans to defense contractors to discreetly supplement the politically sensitive defense budget—a funding strategy dubbed the “credit scheme”

It was then that I recalled the Russian defense sector’s quiet history of off-budget “credit scheme” financings. Back in 2007, Vladimir Putin launched a high-profile rearmament program. His promise to Russia: deliver Soviet-era military strength without Soviet-style economic mismanagement.

But within 3 years, the program had gone off the rails. His initial rearmament budget—highly unrealistic and poorly managed—quickly disappeared into the blackhole of Russia’s military industrial complex with little to show in return.

It was an embarrassing scandal, and it posed a dilemma. To get the program back on track would require a major increase in spending. But a big hike in the defense budget risked undermining Putin’s carefully cultivated image as a responsible steward of the public purse.

As it would many years later with Gazprom, the Kremlin turned to Russia’s corporate credit markets for a funding solution. Dubbed the “credit scheme,” it involved banks making sizeable state-guaranteed “loans” directly to arms manufacturers. It was launched on New Years Eve 2010, with an edict issued by then Prime Minister Putin. As Julian Cooper, a veteran scholar of the Russian defense sector, observed not long after:

“[the] resort to sizeable state guaranteed credits is also a means of supplementing the defence budget: the real volume of military expenditure is now larger than shown by the budget alone.”7

In short, the “credit scheme” enabled the Kremlin to manage the politically sensitive problem of high defense costs by discreetly funding a portion of them “off-budget” with the help of the banks.

The credit scheme suffered from structural flaws—especially the need for frequent bail outs by the state—but it proved politically expedient in the decade up to 2022.

Over the short-term, this scheme worked quite well. But it suffered from two fundamental flaws. First, many of the borrowers couldn’t repay the debt—in fact, they probably struggled just to service the interest. Starting in 2016, the state had to step in almost annually with large bail outs that got discreetly booked in classified sections of the budget. The heavy debt burden impeded the performance of the contractors. And it created risk for the lending banks, which appear to have suffered losses despite credit support from the state.

Despite these problems, however, the state remained committed to this off-budget funding scheme and encouraged its expansion. Levering up the defense sector with debt helped reduce the headline number on the defense budget—and that it seems was deemed a good thing.

The Kremlin greatly expanded this off-budget defense funding scheme in 2022, even passing legislation obligating banks to lend on terms unilaterally imposed by the state

In the run up to 2022, as the Kremlin was planning how to pay for the extraordinary costs of a full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the large-scale occupation that could follow, it saw this off-budget credit scheme as an important part of its war-funding strategy.

But here it ran up against the second flaw in the credit scheme. To work, the banks needed to be on board, since it was their credit creating capacity that allowed the scheme to work. But the banks appear to have sustained losses in the 2019/2020 bailout had reportedly soured on lending to the problematic sector.

When it comes to getting the banks to cooperate, the Kremlin, of course, can always twist arms and call in favor. But doing that at scale is cumbersome and inefficient. So, to make sure the banks didn’t drag their feet about taking more exposure to bad credit risks, the Kremlin did something quite remarkable. In December 2021, it quietly introduced legislation legally obligating banks to extend preferential loans to defense-related companies on terms unilaterally set by the state—size, maturity, credit qualifications, everything. In short, on the eve of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin was formally seizing control of defense-related lending at Russia’s leading banks. The law was passed and signed into effect on February 25th, 2022, as Russian armored columns continued to pour across the Ukrainian border.

Outline of the report

This report focuses primarily on what happened next: how Moscow has used the off-budget funding scheme as a stealthy component of its overall war funding scheme. It estimates the size of the scheme and shows it to be material relative to defense budget spending. It explores Moscow’s rationale for relying on this scheme—which appears to be similar to what it had been prior to 2022: to manipulate public perceptions around defense spending for political gain. And it identifies how the flaws inherent in the regime have elevated systemic risks—especially credit risks—in Russia, as the state has relied excessively on this flawed system of hidden state borrowing to cover its mounting war costs. It concludes with thoughts about how Moscow’s loosening grip over its key sources of cash is likely to weigh on its war calculus.

Chapter 1 reviews Russia’s anomalous and large-scale corporate credit surge and benchmarks it against the federal budget.

Chapter 2 examines a striking discovery the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) made during its ongoing struggle to tame high inflation by cooling corporate borrowing. As it has hiked the key rate from 7.5% to 21%, it observed a “highly heterogeneous” response by borrowers. Debt levels among companies borrowing at normal market terms stopped growing—as expected. But borrowing by a second group of companies enjoying state-backed “preferential loans” continued to surge upward, “insensitive” to rising rates.

Chapter 3 recounts the rise of systematic state-backed preferential lending to fund the defense sector. It tells the largely untold story of the “credit scheme” (кредитная схема), briefly described above, including a remarkable twist in the plot that occurred in late 2021, when the Kremlin was planning funding for its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Intent on expanding the credit scheme to fund invasion and occupation but apparently concerned the banks might not be fully cooperative, the Kremlin quietly pushed through a new law imposing full state control over all war-related lending at Russia’s leading banks. It was a classic state-capitalist power move.

Chapter 4 analyzes Central Bank sectoral data on corporate lending to determine whether the scale of state-directed, off-budget lending for the war is a material part of Russia’s overall war funding strategy. It measures lending growth in 15 war-related sectors and estimates how much of that has gone to fund war-related goods and services. Even on conservative assumptions, off-budget lending appears to have been a material part of Russia’s war funding strategy. The quantitative and qualitative analysis used to identify the industrial sectors engaged in war-related activities is presented in Appendix 2.

Chapter 5 addresses the question of Russia’s motive for relying so heavily on off-budget funding for the war, rather than funding more of it through the state budget. It runs hypothetical analysis showing how consolidating all Russia’s war costs on the state budget could have substantially increased both the defense budget and state borrowing needs. It argues that the credit scheme continues to serve the same function as it did prior to 2022: to gain political advantage by manipulating public perceptions around the size of Russia’s defense spending. By limiting visible spending in the budget, the credit scheme helps Russia’s war finances appear “surprisingly resilient,” “sustainable,” and facing no significant risk. That image enhances Russia’s bargaining power in any eventual negotiations.

Chapter 6 observes how Moscow’s excessive reliance on its off-budget credit scheme has elevated systemic economic risk in Russia, especially credit event risk. The CBR has identified corporate credit growth as the primary driver of Russia’s high inflation and state-directed preferential lending as the main driver of corporate credit growth. That means Moscow’s off-budget credit scheme is helping fuel inflation.

Beyond inflation, the Kremlin’s off-budget credit scheme is elevating systemic credit risk—in 3 ways.

(i) by increasing financial distress in the “real” economy. The CBR says the rate insensitivity of preferential lending weakens the effectiveness of rate hikes; only “real” economy companies curb borrowing. Consequently, to achieve its inflation targets, the CBR must hike even more aggressively. That has driven rates to prohibitive levels (21%), increasing the risk of financial distress in the real economy—as reports of looming bankruptcies in the coal mining sector reflect.

(ii) by eroding credit quality and weakening regulatory oversight in the banking sector. The CBR has voiced concern over “aggressive” lending, and inadequate liquidity and capital buffers in the banking sector, brought on in part by a 2022 relaxation in macroprudential policies in response to sanctions. Worse still, prior to 2022, the CBR is reported to have greatly eased reporting and monitoring requirements around defense-related lending. Consequently, it’s possible financial sector loan statistics look healthier than they really are—and neither the regulator nor the banks themselves have an accurate read of the true levels of risk exposure;

(iii) by increasing the likelihood of large-scale restructuring needs among war-related borrowers. A ceasefire will likely deliver a double-blow to war-related borrowers: a reduction in contract revenues and access to soft loans. A large wave of defaults could ensue crystallizing credit risk at the banks and imposing an immense bailout burden on the state.

The Conclusion observes that wars are fought on cashflows, and that the Kremlin has gradually been losing control over its 3 key sources of cash: (i) its sovereign wealth fund, (ii) oil and gas revenues and (iii) domestic borrowing. It argues that this is likely to weigh on Russia’s war calculus in 2 ways: (i) Moscow will be less inclined to believe time is on its side—the longer it must fund elevated war costs, the greater the risk that credit-related events weaken its negotiating leverage; and (ii) Moscow will prioritize sanctions relief aimed at boosting cashflows to help with politically perilous post-war debt restructuring and rearmament.

The report Appendices include, among other things, a technical discussion laying out the quantitative and qualitative analysis used in screening the sectoral data used in the report.

This report differs from some other assessments of Russia’s war finances because it looks at Moscow’s overall war-funding strategy rather than focusing on the published defense budget.

Some readers may be aware of earlier Western assessments of Russia’s war-funding capacity that may appear to be at odds with the findings of this report. That’s mostly because we look at different data sets and ask different questions.

Many previous assessments of Russia’s war finances focus on Russian budget data—its revenues and expenditures. Based on those numbers, they conclude—not unreasonably—that Moscow’s war finances appear “surprisingly resilient.” And they often interpret elevated levels of defense allocations in the 2025 and 2026 budgets to mean that Russia is ready and able to fund a long-term war of attrition.

Some assessments conclude that the main risk to Russia’s war finances is oil price. Sophisticated analysis, such as that by Richard Connolly and Dara Massicot, also astutely point out that in the event of a major retreat in oil prices, the Russian government likely still has plenty of headroom to borrow (though it will now have to pay nearly triple the rates of late 2022).8

This report does not take a view on the sustainability of Russia’s published defense budget. It sees the published defense budget as part of a broader war-funding strategy, which includes the off-budget credit scheme—the main focus of this report. In some ways, it is complementary to those budget-focused assessments.

This report seeks fresh insight into Russia’s war finances by looking at underexamined evidence of large-scale, off-budget funding in the corporate credit markets. It’s hoped that other researchers will choose to train their skills on Russia’s extrabudgetary funding schemes. As they do, our understanding of Russia’s war finances is likely to evolve. We’ll be more likely to recall Aleksei Kudrin’s prophetic 2012 warnings of a profligate rearmament program that would impoverish Russia’s future. And our head-scratching over Russia’s “surprising resilience” will soon give way to talk about the Kremlin’s all-too-habitual imperial overreach.

For policymakers, this report identifies a new dimension of Russia’s war-funding strategy and flags risks arising from it—especially systemic credit risk—that could constrain Moscow’s war finances and weigh on its war calculus.

For policymakers, this report identifies a new dimension of Russia’s war-funding strategy: a heavy reliance on off-budget debt to supplement its defense budget allocations. It also shows how excessive reliance on this off-budget funding strategy has elevated systemic credit risk to a point that it could become a constraining factor on Moscow’s war finances and weigh on it war calculus.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the generosity of many friends and colleagues who have taken the time to engage with analysis in this report and provide valuable feedback. This report has also benefited greatly from the insightful research of other analysts and scholars, some of which is cited in the notes to Chapter 4 and Appendix 2.

Chapter 1: Russia’s Anomalous Corporate Credit Surge

“War made the state, and the state made war.”

—Charles Tilly9

Russia’s wartime borrowing is immense—but it’s not where you’d expect to find it.

Wars are notoriously expensive. To soften the impact on taxpayers, states routinely finance wars with debt, spreading costs out over time.

Russia’s war on Ukraine should be no different. As the largest war in Europe for seventy-five years, waged under extensive sanctions, you’d expect to see large-scale borrowing to finance formidable costs. And, indeed, we do see a large, anomalous spike in Russian borrowing since mid-2022. It’s just not where you’d expect it to be. Instead of accumulating on the state’s balance sheet as it often does, Russia’s wartime debt surge has built up on company balance sheets across the corporate sector.

Since Russia shifted to a war footing in mid-2022, Russian companies have increased their outstanding debt by 71%, amounting to ₽36.6 trillion or $446 billion in incremental borrowing

For years prior to 2022, Russian corporate debt grew at a modest pace (see Figure 4). From July 2022, however, it abruptly began to surge—just as parts of the Russian economy were shifting to a war footing. Through November 2024, Russian companies added ₽36.6 trillion to their outstanding debt. That converts to $446 billion at historical rates (see Appendix 1). Corporate bank loans, which make up most borrowing, surged by 76%, with some sizeable corporate sectors doubling, even tripling their borrowing from banks.10

Figure 4

This corporate credit surge is large by comparison to budget metrics, significantly exceeding state borrowing, the defense budget, and total oil and gas revenues over the same period.

In the context of Russia’s economy, ₽36.6 trillion is a large number. It comes to 21.3% of 2023 GDP and equals total federal budget revenues for 2024.

The corporate credit surge is also significantly larger than certain key budget figures pro-rated across the same time period (see Figure 5). It is:

1.9 times larger than the Russian defense budget;

1.5 times larger than total oil and gas tax revenues; and

7 times greater than incremental government borrowing.

Figure 5

What explains Russia’s corporate credit surge? It has exhibited some unexpected behavior, including a lack of responsiveness to rate hikes.

What accounts for this curious, abrupt and relentless surge in corporate borrowing? No doubt a number of factors are behind it. For example, a short-lived boom in residential housing has likely driven some of the loan growth in building construction. And large borrowers like Gazprom that used to fund abroad are now largely reliant on the domestic credit markets. But the corporate surge is immense, and such factors appear to account for only a fraction of it.

What’s more, the corporate credit surge has also exhibited some unexpected behavior. It began in mid-2022, exactly at the time that Russia began shifting large parts of the economy to a war footing. Since, it has had 29 months of continual growth (see Figure 6). Even more notable, it continued its relentless surge despite two aggressive rounds of rate hikes by the central bank.

Figure 6

Fortunately, we aren’t the only ones trying to understand what’s driving the corporate credit surge. The Russian Central Bank (CBR), too, has been scrutinizing the credit surge. That’s because this relentless expansion in credit has been a major driver of Russia’s rising inflation, helping push official levels close to 10%—far above the CBR’s target levels of 4%.

In its analysis of what’s behind the corporate surge, the CBR has made some revealing observations. We examine these in Chapter 2.

Chapter 2: The Relentless Driver of the Credit Surge—State-Directed, Preferential Bank Loans

“Now let us look at where the high demand [driving inflation] has come from that I talk about so often. Household incomes are up, which one can only welcome. Budget spending has grown, which was unavoidable. But the main thing is that lending has grown very strongly, even at an unprecedented rate.”

—Head of the Russian Central Bank, Elvira Nabiullina, addressing to a joint session of the Russian parliament, November 19, 2024.11

“In our view, now is the most important time to give serious thought to a more flexible system of state-sponsored support. We’re actively discussing this with the Government. It should not be limited primarily to preferential lending. Of course, everyone has gotten used to preferential loans - both businesses and ministries.”

—Head of the Russian Central Bank, Elvira Nabiullina, addressing to the State Duma, October 31, 2024.12

Why, despite two rounds of aggressive rate hikes, has the Central Bank struggled to constrain the corporate credit surge?

“The situation is highly heterogeneous.” Those were the words the Russian Central Bank (CBR) governor used in November 2024 to describe an alarming development in the corporate credit markets. During the previous 15 months, the CBR had conducted two rounds of aggressive rate hikes in an effort to cool off the corporate credit surge. Unrelenting corporate borrowing had become the primary driver of rising inflation. Yet, despite raising the key rate from 7.5% starting in July 2023 to a record level of 21% by October 2024, the CBR was struggling to slow the unrelenting expansion of corporate credit.

After its tightening round, from July through December 2023, when rates had more than doubled to 16%, the CBR thought it had gotten borrowing under control (see Figure 7). But its victory was short-lived. By Q2 2024, borrowing was once against accelerating, which led to a second round starting in late July 2024.

Figure 7

Consumer borrowing fell sharply, helped by the termination of a popular program of state-subsidized home mortgages in July. But corporate borrowing continued to surge to record highs, much to the consternation of the bank. Indeed, the second round of tightening saw the largest increase in corporate debt of any three consecutive months of the corporate credit surge (see Figure 8).

Figure 8

The corporate debt market has split into groups of borrowers: (1) a rate-sensitive group that has curbed its borrowing and (2) a group that is largely “insensitive” to rate hikes and continues taking on new debt

What was driving the surge? Why was it so unresponsive to tightening? For months, the CBR had been gradually piecing together the puzzle. By November 2024, it had an answer.

The market for corporate loans had split into two distinct groups—become “highly heterogeneous” in the CBR’s terminology. One group was borrowing at market (on normal market terms). This at-market group responded as expected to a sharp rise in rates: they curtailed their lending. The second group, by contrast, was borrowing off market, receiving “preferential” terms of credit (льготное финансирование). It was this group of “preferential” borrowers that was proving largely “insensitive” to rate hikes.

This rate-insensitive group has blunted the effectiveness of the CBR’s main inflation-fighting monetary tool: rate adjustments

For the CBR, the “insensitivity” to rates shown by these preferential borrowers posed a major challenge. The rate hike is its primary tool for fighting inflation. But if a large class of borrowers is immune to higher rates, the CBR is greatly disadvantaged in its fight against inflation. As the CBR observed:

“Preferential loans are weakly sensitive to changes in monetary policy. The larger their share, the more the key rate needs to be changed to influence credit activity, demand and inflation.”13

In other words, to cool down lending when preferential loans are prevalent, the CBR needs to hike even more aggressively than it would normally have to do.

This, however, has a perverse and undesirable effect: it squeezes out the most efficient users of capital, those borrowing “at market”—while the normally less efficient preferential borrowers continue to take on debt. So, rate hikes were doing significant damage to the “real” economy while having limited impact on the remaining driver of credit expansion—the preferential borrowers.

These rate-insensitive borrowers come from certain sectors, have revenues tied to state-contracts and receive state-directed “preferential” bank loans, often with low interest rates

Who, then, were these rate-insensitive, preferential borrowers? From CBR commentary on the problem, the following portrait emerges. They are associated with certain industrial sectors;14 their business is closely “tied to state orders”15 and “state contracts”;16 the state provides these borrowers with support in the form of “preferential” borrowing terms;17 credit support from the state can take a range of forms, including principal guarantees.18 But for these borrowers, support is often taking the form of interest rate subsidies, where the borrower pays a fixed rate well below the normal market rate and the state pays the lending bank the difference between the market rate and the “preferential” rate.19 In a high-rate market, the demand for such loans becomes very strong, and can even exceed the needs of the borrower.20 Quantifying preferential lending is a challenge21 because the CBR lacks comprehensive data.22

In short, Russia’s rate-insensitive corporate borrowers are companies that tend to do government contract work in certain unspecified sectors; in connection with those contracts they receive state-directed, preferential bank loans—routinely with subsidized interest rates; and their relentless demand for credit during the second tightening round (August – October 2024) was so strong that it pushed corporate borrowing to a new 3-monthly record, even as incremental demand from at-market borrowers dried up.

Conventional borrowing is driven by commercial calculations, while state-directed, preferential borrowing is driven by the state’s political agenda.

The essential difference between conventional, at-market borrowing and state-directed preferential borrowing boils down to the nature of the credit decision. With conventional borrowing, the decision is driven first and foremost by the commercial calculations of company management. With state-directed, preferential loans, however, it is the strategic priorities of the state that drive the borrowing decision. The state adjusts borrowing terms and conditions in pursuit of its political agenda.

What could be so important to the state that it would allow preferential borrowing to thwart the Central Bank’s battle against inflation?

By late October, the CBR seems to have understood its conventional monetary tools were inadequate to rein in the corporate credit surge. Higher rates were having little effect on borrowing. Insatiable credit demand from rate-insensitive, preferential borrowers was, in effect, stripping the gears on Russia’s monetary transmission mechanism.

How then to tackle the problem of unyielding preferential borrowing? Since this borrowing is driven by political, not commercial, objectives, the CBR recognized it would need a political solution. So, on the 28th of October, the CBR head met with Vladimir Putin and other senior officials to discuss what Putin described as “a sensitive and important topic—the dynamics and structure of [Russia’s] corporate debt portfolio.”23 Three days later, she would also present her case in a speech to the Russian Duma where she called for the curbing of state-directed preferential lending. We will return to these meetings in Chapter 6.

While the state uses soft financing to pursue various agendas, the scale and timing of the corporate credit surge strongly suggests much of this preferential lending is being used to fund the war.

Throughout its public commentary on preferential lending, the CBR remains vague about the specific nature of the state demand that is driving it. No doubt, it’s a mix of things. The state has been using various forms of soft financing for a range of projects, from agricultural subsidies to port and rail construction.

Those needs, however, have been around for years and have never fueled a major credit surge. And while they are priority areas of investment—especially agriculture—we can see from sectoral borrowing data these sectors account for only a small fraction of Russia’s incremental borrowing.

What, then could it be? Three clues points strongly to one answer:

the surge in borrowing coincided with the shift of much of the economy to a war footing in mid-2022;

since then, there have been major increase in budget funding for war-related state contracts; and

whatever these borrowers are doing for this state, it must be of immense importance, if the state is willing to sign off on record levels of new corporate borrowing at the same time the CBR is ratcheting rates to record highs in a desperate effort to cool off lending.

The obvious answer these clues point to is that this wave of preferential lending is being used to fund companies engaged by the state in the war.

In the next two chapters, we shall examine the data around this question. If, indeed, much of this state-directed preferential lending is going to fund the war, it wouldn’t be the first time the state relied on such off-budget credit funding to supplement the defense budget. As we shall see in Chapter 3, for over a decade prior to 2022, the state was regularly and discreetly funding a significant portion of its rearmament program using similar state-directed preferential bank loans.

Chapter 3: How the Kremlin Seized Control of Defense-Related Bank Lending

“an authorized bank shall be required…to provide defense contractors and subcontractors with preferential financing on terms set by the government of the Russian Federation for the purposes of fulfilling state contracts and state defense procurement contracts.”

—Amendment to the Law on State Defense Procurement, signed into effect on February 25, 202224

In February 2022, the Russian state quietly and formally seized control of defense-related lending at Russia’s leading banks when an amendment was passed to the Law on State Defense Procurement.

To understand what’s behind much of Russia’s corporate credit surge—and, indeed, much of what afflicts the Russian economy today—a good place to start is a largely overlooked amendment to the Law on State Defense Procurement. It states that all banks authorized to work in the defense sector:

“shall be required…to provide defense contractors and subcontractors with preferential financing on terms set by the government of the Russian Federation for the purposes of fulfilling state contracts and state defense procurement contracts.”25

This amendment was quietly submitted by the Kremlin to the Russian parliament in December 2021, approved on February 22, 2022 and signed into law by Putin on February 25, 2022—as Russian columns continued to stream across the border into Ukraine.

The “authorized banks” mentioned in the law refer to a list of banks approved for managing financial transactions for state defense contracts. These include a handful of Russia largest banks as well as several banks with close ties to Russia’s defense sector.

Banks would be obligated to extend preferential loans to defense-related businesses on terms unilaterally set by the state

In its brief commentary on the amendment, the official government newspaper, Rossiiskaia Gazeta, elaborated on the kinds of preferential financing terms the state might be setting:

“they include the size of loans being received, the conditions of their repayment, as well as any requirements concerning the financial condition of the borrowers and their creditworthiness.”26

While the amendment may be short, its implications are far reaching. It amounts to the state’s commandeering of the credit resources of Russia’s leading banks to fund its war needs. It deprives the banks of all discretion over the lending decisions to defense-related companies and cedes those authorities to the state. Exercised to its full extent, this law would be tantamount to state expropriation of the banks.

In the next chapter, we shall look at just how far the state has gone since 2022 in exploiting these powers to direct preferential bank loans to a wide range of companies now engaged in Russia’s war.

For a decade prior, the state had already been directing banks to make preferential loans to defense contractors to cover shortfalls in defense budget funding for rearmament.

In this chapter, however, we go back in time to gain insight into the roots of the February 2022 amendment. As it turns out, funding Russian defense contractors with state-directed preferential bank loans was hardly a new idea in 2022. For over a decade, the state had been systematically using preferential bank loans to cover substantial shortfalls in budget funding for Russia’s costly rearmament program. We shall look at why the state resorted to this as part of its defense funding strategy and the inherent flaws in this strategy—flaws that have gone unaddressed and pose a significant risk to Russia’s defense finances going forward.

In 2007, Putin launched a high-profile rearmament program, but by 2010 it was mired in embarrassing scandal and cost overruns.

As in 2022, in 2010 the Russian state faced a crisis in its defense industry, one it would end up addressing with help from its banks. Just 3 years earlier, In 2007—with coffers swelling from high oil prices and productivity gains from imported oilfield technology—Putin launched a major 8-year rearmament program. His promise to the Russian people: restore Russia’s Soviet-era military might while avoiding Soviet-style economic mismanagement.

By 2010, however, Putin’s grand rearmament program was in trouble. Cost budgets had been far too optimistic, while Russia’s production capacity had been greatly overestimated. Less than halfway into the program, funds were already running low with little to show in terms of new production. Putin was forced to abandon the old program and announce a new, ten-year program with a significantly higher price tag. A deputy minister was dispatched to explain that this time they had gotten the math right and wouldn’t make the same mistakes again.27

A major spending increase was needed to get back on track, but this risked tarnishing Putin’s carefully managed image as a prudent manager of the public purse.

The Kremlin was interested in avoiding a sudden and dramatic step up in defense spending, so it wanted to backload the plan, pushing some 70% of the expenditures out to the second five years. This presented a dilemma, however, because contractors needed more money straightaway if they were to get back on track. Putin faced a stark choice: scale back his rearmament ambitions or risk appearing soft on spending discipline.

A solution was found: the state would limit budget increases by discreetly arranging state-guaranteed bank loans to arms manufacturers to cover their funding shortfall.

A solution was soon found that would get more money to arms contractors without adding more costs in the budget...at least not straightaway. The state would arrange for several large Russian banks to provide 5-year loans to arms manufacturers to supplement the inadequate funding coming from the state budget.

There was only one hitch: the banks appear to have been unwilling to lend without a repayment guarantee from the state. That was not at all unreasonable. The sums involved were large, while many of the borrowers of record were likely to be very high credit risks. Many will have been heavily dependent on state contracts—which were still being negotiated—so their future revenue flows were uncertain. And many were largely unreconstructed legacy defense enterprises from the Soviet era with highly opaque cost-structures.

To address this problem of repayment, the state offered to the banks to guarantee the principal (but not the interest) of the loans. And on December 31, 2011, an edict was issued by then Prime Minister Vladimir Putin spelling out the terms.28 Judging by the subsequent amendments to this edict, new 4- or 5-year loans continued to be issued under this guarantee facility at least into 2016.29

This lending program wasn’t classified. There are odd references here and there, but there seemed an effort to play them down. When, for example, the Duma was rushed to approve enabling legislation, the head of the Defense Committee described them in a floor statement in nearly impenetrable bureaucratese:

“a new, important mechanism related to the formation and stimulation of the implementation of state defense orders, which consists of the provision of state guarantees.”30

By 2016, however, the cash-poor arms contractors predictably could not repay much of their debt. The state then paid off the banks under the guarantee agreement.

Over the next several years, little was said about these loans as they steadily accumulated on the balance sheets of Russia’s arms producers. By 2016, however, some ₽1.2 trillion in debt (an estimated $37 billion at historical rates) had built up, and some two thirds appears to have gone bad, with trouble on the way. That’s when the state had to step in and perform on its guarantees by repaying the loans. To fund this repayment, it needed money from the budget. And because it was a sizeable amount, some public explanation was required, which brought the loans back into the public eye.

In October 2016, addressing the Duma’s budget committee, Finance Minister Anton Siluanov offered the following brief explanation for what was behind the state’s supplementary funding need. Referring back to the late 2010 edict he explained:

“It was decided that arms manufacturers would take out loans with state guarantees so that they could more quickly implement the state armament program and fulfill the president's order to rearm our army within the allocations provided in the budget. These loans were used to manufacture products for military use.”31 [author’s emphasis]

Funds, of course, were duly allocated and tucked away into an expanded, classified part of the budget.32 A year later, in October 2017, Siluanov would be back asking for another ₽200 billion to repay debt borrowed under the state-guarantee.33

Despite the default, the “credit scheme” worked well for the state, by keeping a significant portion of defense costs off the budget for years. More loans were forthcoming.

In effect, then, through this state-directed “credit scheme” the state had managed to arrange five years of supplementary “off-budget” funding for defense procurement before it had to pay a single ruble from the budget. While there continued to be criticism from some quarters about excessive defense spending, this rollover of the “credit scheme” did not garner that much media attention. The Kremlin’s illusion of a financially disciplined rearmament program remained largely untainted.

Which perhaps made the rest of Siluanov’s statement to the committee easier to understand. By “repaying the so-called enterprise loans” the state would be “freeing these enterprises from their debt burden, so that they had the opportunity to borrow again”34 [author’s emphasis].

By 2019, debt distress in the sector had grown severe enough that Putin had to intervene and a difficult restructuring plan was negotiated with the banks.

And borrow they did. By the end of 2019, sector debt had grown still larger, to ₽2.7 trn and the sector was in distress again—an entirely predictable outcome. Banks and their borrowers were at loggerheads. But it’s not clear how much of this debt was fully backed by explicit state guarantees. The banks were demanding the state to step in and assume the bad debts, while defense contractors called for “non-productive” bankers to write off the debt.35 The debt load had become so onerous, it was impeding progress with rearmament.

Things had gotten bad enough that Putin had to publicly weigh in on the matter. He convened a meeting of senior officials to discuss the euphemistically named “program on the financial recovery of defence sector organizations.” He sanctimoniously harangued arms manufacturer for the “large debt burden” they had accumulated. It had become, he said, “the restraining factor” that was “seriously limiting the possibilities for diversifying production [and] introducing advanced technologies.”36

This, however, was the Kremlin passing the blame onto others for it own policies. It was Putin, after all, who had been Prime Minister in 2010 and whose name is at the top of governmental edict establishing the original “credit scheme.”

In due course, a compromise restructuring was agreed for part of the debt. The details were once again classified, but reports suggest the state assumed a portion of the bad debt, and forced lenders restructure the rest with long maturities and low interest.37

The state responded with a sector audit, but remained committed to state-directed preferential lending

How did the state respond to the second major sectoral debt crisis in less than five years? It did two things.

First, it launched a widespread financial audit of the defense sector. With debt continuing to accumulate in the sector, it appeared to be seeking a better understanding of how great the insolvency risk was. The audit came back in 2020 with reports of significant financial distress, with some companies crushed by debt-to-EBITDA ratios running into double digits. And these heavy debt loads were weighing on progress across the defense sector. As the head of the commission had once described the impact of the debt burden: “now the defense sector is an exercise bicycle: you crank the pedals, but you don’t go anywhere.”38 Following the audit, he went on to observe that the debt problem must be solved for the sector to make further progress.39

Second, the state advanced its plans to develop a special, state-owned bank, Promsviaz’ Bank (PSB), dedicated to the defense sector. After the painful experience of the 2019-2020 settlement, some of the banks authorized to service the defense sector had cooled on more lending to the sector. The plan was that PSB would, in time, consolidate much of the sector banking business. In theory, consolidating sector banking into a single institution would also give the state better control over sector finances. And PSB began issuing preferential, low-interest-rate loans aimed at reducing the risk of financial distress.40

The off-budget “credit scheme” shouldn’t be thought of as real corporate lending, since there seemed to be little reasonable expectation that much of it would get repaid.

What are we to make of this decade of chronic debt and default? One way to describe it is as a Kremlin conjuring trick: by levering up the defense sector with debt, the Kremlin appears to be making good on its promise to deliver soviet-era military strength while keeping the defense budget in check. As Julian Cooper, a veteran scholar of the Russian military, would astutely observe not long after:

“[the] resort to sizeable state guaranteed credits is also a means of supplementing the defence budget: the real volume of military expenditure is now larger than shown by the budget alone.”41

The fact the state was levering up the defense industry to get better returns on its budgetary investments is not in and of itself a conjuring trick, nor a betrayal of its public promise. For many businesses, having some debt in the capital structure is advisable, provided there’s a reasonable expectation they can manage the load.

And it’s exactly that “reasonable expectation” that seems to have been missing here from the very outset. There’s a reason the banks received state guarantees on their loans under Putin’s edict No. 1215 from 2010. It’s because all the key players—the borrowers, the lenders and the state—almost certainly knew Russia’s legacy defense sector was an unacceptably high credit risk. Many borrowers would struggle to repay the debt they were being forced to take; they might even struggle to service the interest payments. And scholarly research throughout the 2010s has repeatedly confirmed the weak financial state of much of the sector.42 And the cycle of borrowing and default briefly recounted above bears out the research.

The sector had chronically weak finances owing to underpriced state contracts, corruption and the assumption among managers that the state would bail out their bad debts.

Several reasons account for the chronically poor financial state of the sector.

First, there is what has been called the “pricing problem” (проблема ценообразования). Around 2008-2010, under then Defense Minister Serdiukov, the state reportedly became more aggressive and adversarial in its pricing of arms procurement contracts, pushing prices below what contractors claim they needed to cover costs and expenses. As an effective monopsonist, the state had superior bargaining leverage over the contractors and had begun to exercise it. Arms manufacturers had little choice but to sign contracts, even they could well result in losses.43 For many them, the Russian state was practically the only buyer for their products. This left them chronically short of cash.

The second reason was corruption. Part of the state’s rationale for low-balling contract prices was an effort to crack down on corruption, which was (and remained) rampant in Russia’s arms procurement. Price structures were highly opaque, cronyism rampant, and management often had little incentive to want cash to accumulate on the balance sheet.

Third, of course, was moral hazard. If the state had guaranteed this debt already, why should enterprise managers make provisions for debt repayment?

On top of it all, interest expense on these loans was only adding to the cashflow shortfalls at many of these companies. That was a finding of an Audit Chamber investigation into defense sector finances published in early 2013 It went on to add that a majority of defense sector enterprises were so technologically antiquated, that it would make more sense to build new factories from scratch than upgrade existing plant.44 The heavy burden of interest charges was also evident in the 2020 special audit.45

The “credit scheme” is better understood as hidden state borrowing, or “state-directed, off-balance-sheet debt funding” to be more technical.

Sector companies may be the borrowers of record, but the de facto borrower here is the state. These are cash injections that the state has “compelled” the companies to take—in lieu of fully priced contracts—so that they can cover their production costs. And it was the state whose credit the banks were counting on when they disbursed the funds. And it was the state that repaid the loans when they came due. Moreover, in many cases, there probably was never any reasonable expectation that the borrowers of record would be able to repay the debt themselves.

So, what in effect, we have is a case of “sham” borrowing, or “hidden” state borrowing, as the IMF might put it. The state is orchestrating these loans, providing the enabling credit and then paying them off.46 A more precise, though clunkier, label might be “state-directed, off-balance-sheet debt funding.” The state is using its credit to raise debt to fund the companies but directing the banks to structure the debt as company loan so that it stays off the state’s balance sheet until it’s time to repay.

And the state’s motive was clearly to provide supplementary defense funding above and beyond was was readily visible in the federal budget.

As to the state’s motive, two officials have provided similar explanations: it was to provide adequate funding for defense contractors while also limiting defense budget expenditures. We’ll recall Siluanov’s 2016 explanation to the Duma. He explained the purpose of the loans was to "implement the state armament program and fulfill the president's order to rearm our army within the allocations provided in the budget”47 (author’s emphasis). In 2011, a deputy defense Minister put it more bluntly: “Taking on state-guaranteed loans to carry out defense orders…is a compelled measure. The reason for it is that spending allocations in the armament budget are very unevenly planned: 31% for 2011-2015 and 69% for 2016-2020.”48

As often with “hidden” state borrowing, it’s riskier and costlier than normal state borrowing. In this case, it has worsened financial distress throughout the defense sector, led to disruptive debt restructurings, and created significant financial risk for Russia’s leading banks. It would have been far less risky, disruptive and costly had the state simply borrowed the money directly in the bond markets and used it to pay higher prices in its procurement contracts.

But state’s using “hidden” debt are often willing to put up with these costs and risks—to a point—as the price of achieving a desirable political outcome—often in the form of politically advantageous optics. In Moscow’s case, it appears to have found its off-budget “credit scheme” a useful—albeit somewhat unwieldy—tool for reducing the headline numbers on Russia’s defense budget and delivering on Putin’s promise to restore military strength without fiscal mismanagement.

More precisely, it was a form of hidden, supplementary revenues to compensate for underpriced contracts.

Pavel Luzin has characterized the peculiar function of these loans very well in his insightful 2020 essay, “Russia’s arms manufacturers are a financial black hole.” He observes that these loans “do almost nothing to increase [the] profitability” of these companies. Instead, preferential bank loans might:

“allow the state to compensate the military industrial complex for its losses through other budgetary streams — without publicly inflating its defence and security expenses.”49

In short, the state is using its hidden borrowing to pay what amounts to hidden revenues to the companies to help keep them afloat.

For the “credit scheme” to work, the state needs the credit-creating capacity of the banks. But banks had begun to sour on the high-risk defense sector.

Companies might have little say in whether they get compensated with more richly priced contracts or loans they don’t have to repay. They were “compelled” to take out the loans. But banks, in theory, did have a say—at least until February 2022, when the government passed the amendment commandeering them to fund the war. After banks apparently took some losses in the 2019/2020 bailout,50 it appears some banks were souring on the more lending to the sector. Promsviazbank was poised to consolidate sector debt.

To remove the risk of bank reluctance and make the credit scheme fit war-time use, the Kremlin put forward legislation giving the state full control over defense lending at the banks.

It appears, however, that the Kremlin had second thoughts as it laid plans for a full-scale invasion and subsequent occupation of Ukraine. Defense related costs were bound to soar. The off-budget “credit scheme” could prove a valuable tool both for directing cash quickly where it’s needed, “without publicly inflating” its defense budget, to paraphrase Luzin.

But why pass a law effectively expropriating the banks? If banks are reluctant to lend, they can find ways to drag their feet. Of course, a call from the right senior Kremlin official can often solve a problem. But where lending needs to happen at scale, such ad hoc solutions are impractical. To stop foot dragging and free up senior officials for other things, a law obliging the banks to lend to defense-related borrowers on terms unilaterally set by the state is simply a prudent measure.

As we shall see in the following chapters, however, the extent to which the state has come to rely on this carte blanche credit scheme since mid-2022 is anything but prudent.

Chapter 4: How Big is Russia’s Off-Budget War Debt? A Broad Estimate.

How material is Russia’s off-budget lending to its overall war-funding strategy? CBR sectoral data allows us to broadly estimate its scale.

In this Chapter we address the important question of materiality. How material has off-budget defense funding been relative to defense budget allocations since mid-2022? If it hadn’t existed, would it have been clearly missed?

To answer this question, we need to broadly estimate the amount of state-directed preferential lending that has been extended to war-related companies.

Fortunately, we are able to make such an estimate thanks to sectoral lending data published by the Central Bank. While the data is not sufficiently granular to allow precise, single-point estimates, it is suitable to support a broad estimate that provides a reasonable indication of scale. And for our purposes—establishing materiality—a reasonable indication of scale is all we need.

Even on our most conservative assumptions, off-budget funding appears material to Russia’s overall defense funding strategy

The analysis in this chapter concludes that off-budget defense-related lending makes up a material part of its overall war-funding strategy, even on our most conservative set of assumptions.

Central Bank data break corporate lending into 78 separate industrial sectors, allowing us to estimate borrowing trends of defense-related sectors

As we did when measuring Russia’s overall corporate debt surge (see Chapter 1), in this chapter we are making use of on Central Bank data sets on the Russian credit markets. The main difference is that this data provides ruble corporate bank debt broken out across 78 separate non-financial industrial sectors, covering everything from gambling to oil and gas extraction.51 These sectors follow standard Russian industry classification system known as OKVED2. This allows us to track monthly changes in bank borrowing levels across a wide range of industrial sectors. So, for example, we can see that the outstanding debt of companies involved in “production of motion pictures, video films and television programs, publication sound recordings and sheet music” (#59 in the OKVED2 system) has fallen by 34.3% or around ₽5 billion ($45 million) between mid-2022 and the end of November 2024.

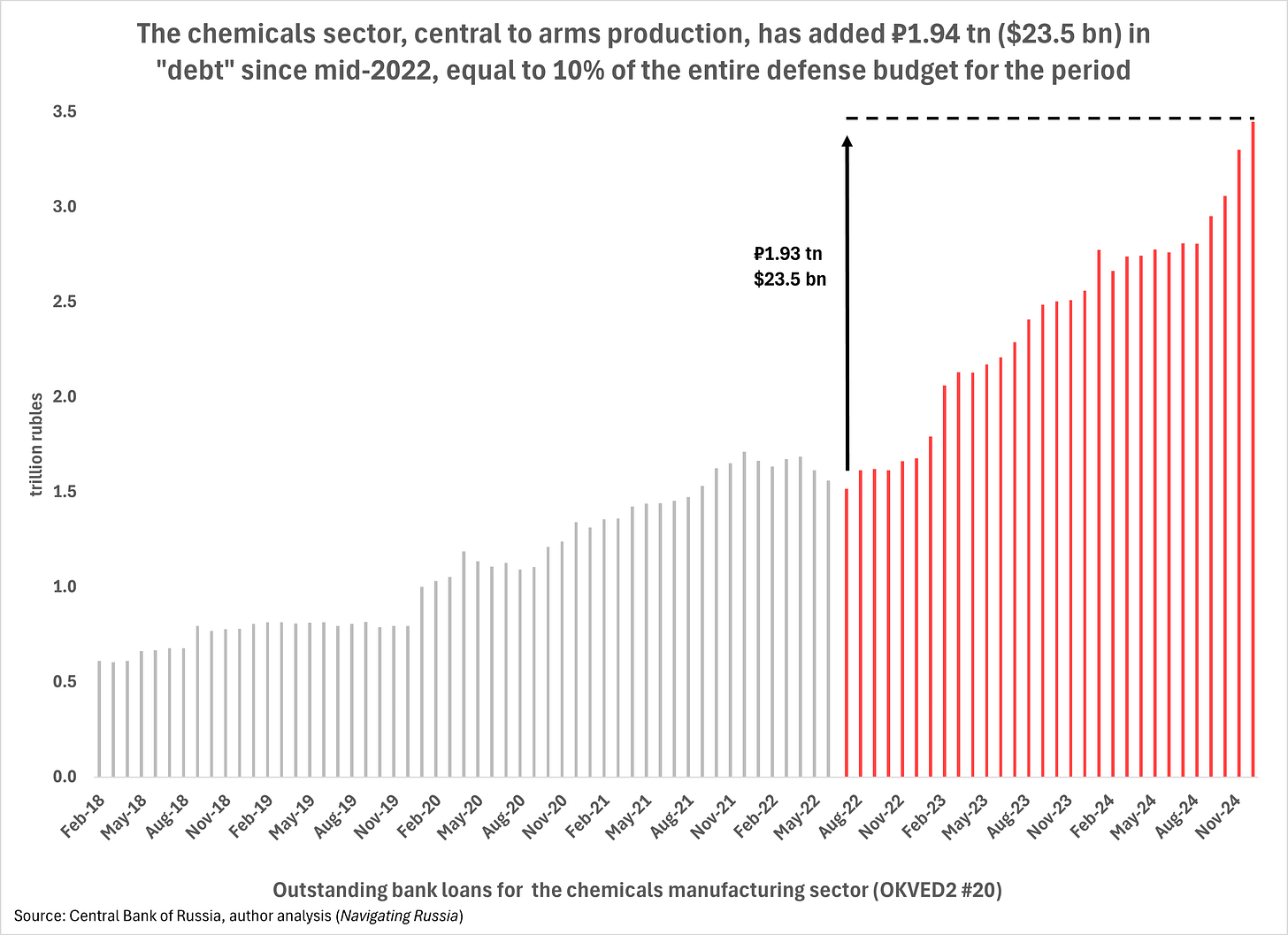

By contrast, companies involved in the “production of chemical and chemical products” (OKVED2 #20) has increased by 127.2% or around ₽1.93 trillion ($23.5 billion) over this same time (see Figure 9). It’s not surprising that the chemicals sector should be taking on more debt during a war; it’s customarily seen by military analysts as one of the 4 OKVED sectors comprising the Russian arms manufacturing industry. Prior to 2022, it was tracked as a proxy for economic activity around Russia’s military industrial complex.

Figure 9

This ₽1.93 trillion in incremental borrowing is, in fact, a large number. It’s equal to 10% of Russia’s entire federal defense budget over this same period. Now, consider that—as a rule of thumb—around half the defense budget goes to arms procurement.52 That means that the amount of “debt” capital injected since mid-2022 just into this single war-related industry sector, chemicals, equals roughly 20% of Russia’s entire estimated arms procurement budget for the same period. That data point alone should alert us to the potential significance of Moscow’s off-budget credit scheme in the overall structure of its war-funding strategy.

15 sectors have been identified as likely to be (i) providing a significant level of war-related goods and services and (ii) receiving substantial amounts of state-directed preferential loans.

Of the 78 industrial sectors in the CBR data, we have identified 15 as directly relevant to estimating the scale of Russia’s off-budget war-funding scheme. The methodology and analysis involved in identifying these sectors is detailed in Appendix 2 and involves the application of qualitative and quantitative screening tests. The screening process has produced a group of 15 sectors that we can say with a reasonable degree of confidence (a) are likely to be providing the state with a significant level of war-related goods and services, and (b) appear to be receiving substantial amounts of state-directed preferential loans.

This list further breaks down into two subgroups:

4 core sectors customarily associated with legacy arms manufacturing (see above); and

11 “other war-related sectors.”

Borrowing behavior of these two subgroups tracks very closely to one another (see Figure 10). At the same time, they also sharply deviate from that of the remaining 63 sectors that did not clear our screening thresholds and are deemed to be “non-war-related.”

Figure 10

Estimating the scale of war-related debt: high- and low-case assumptions

In making our estimate, we will draw on incremental borrowing data from these 15 sectors. We begin by calculating the total increase among the war-related sectors in outstanding bank debt from July 2022 through November 2024. This provides us with a maximum estimate—our “high-case” estimate.

Next, we need to make a risking adjustment to account for the likelihood that not all borrowing in all sectors is state-directed, war-related preferential lending. In our 4 core arms manufacturing sectors, we assume 100% of borrowing is war-related. But in the 11 “other war-related sectors” we assume some incremental borrowing in our data may be unrelated to the war. Our screening process, however, suggests the non-war portion is not likely to be very large. This is evident in how these sectors scored in our screening tests (see Appendix 2). This is also reflected in how closely they track our benchmarks for fully dedicated war-related sectors—the 4 core arms production sectors (see Figure 10).

To be on the conservative side, however, we are running a “low-case” estimate that assumes only 50% of the incremental debt of these 11 sectors is war-related. The conservative quality of that assumption can be seen in the steady upward growth trend over the course of 2024, including August through November 2024, when debt levels among at-market borrowers stopped growing (see Chapter 2).

To summarize our input assumptions:

High case:

4 core manufacturing sectors = 100%

11 other war-related sectors = 100%

Low case:

4 core manufacturing sectors = 100%

11 other war-related sectors = 50%

Figure 11 shows the estimation analysis. Starting from the top down, the black vertical bar labeled 100% is our primary benchmark. It represents the headline defense budget figure, pro-rated for the 29 months running from July 2022 through November 2024.53

Figure 11

Beneath that is our estimated range of state-directed defense-related preferential lending. The dark red band represents our low-case estimate, which comes to 72% of our benchmark. The light-red band represents the range of values between our low-case and our high-case estimate, which totals 118% of our benchmark. The midpoint of the range is 95%.54

At the bottom are two additional benchmarks representing the annual defense budgets for 2023 (on the left) and 2024 (on the right).

Even at the low end of our range, off-budget funding appears material to Russia’s overall defense funding strategy

Even at the low end of our range, the estimated amount of off-budget, war-related lending comes to nearly three quarters of our pro-rated defense budget figure for the same period. As a percentage of total combined pro forma defense spending (budget + off-budget), our estimated range runs between 42% and 54%. That easily meets and exceeds any reasonable standard for materiality.

Chapter 5: Moscow’s Conjuring Trick. How Off-Budget War Debt Keeps the Defense Budget Looking “Surprisingly Resilient”

“everything necessary for the front, everything necessary for victory is in the budget.”

—Anton Siluanov, Russian Minister of Finance, September 28, 202355

“When [the Soviet leadership] wanted to conceal [defense spending levels], rather than invent an outright lie, they preferred either to mislead by giving out half or a quarter of the truth, or else to say nothing at all.”

—Mark Harrison, “Secrets, Lies and Half-truths”56

When announcing the big defense spending increase in Russia’s 2024 budget, the finance minister sent two important messages

In September 2023, Finance Minister Anton Siluanov sent shudders through Western capitals by unveiling a headline defense budget number that was some 68% higher than the 2023 figure. He described the increase with the following words:

“The priorities of the budget are set out in the structure of the budget expenditures. The structure of the budget shows that the main thrust is on ensuring our victory—the army, defense capability, armed forces, fighters - everything necessary for the front, everything necessary for victory is in the budget. This is a considerable strain for the budget, but it’s our unconditional priority.”57

As students of Russia’s Civil War will recognize, this is a bureaucrat’s lumbering riff on Lenin’s much pithier “Everything for the front! Everything for Victory!” (Все для фронта! Все для победы!). But through the verbiage, two messages come through—one pointed, the other more subtle.

Message #1: Russia is ready to spend what it takes to win and willing and able to bear the strain—a message validated by Western assessments.