Moscow’s Fading Shadow Fleet: Russian Oil Revenues are More Vulnerable than Ever

The West has cracked the code on how to roll back Russia’s shadow fleet at scale. This gives policymakers several low-risk, high-impact options for further restricting Moscow’s oil revenues.

Hovhannes Aivazian (Ivan Aivazovsky), Seascape, 1860.

"We don't want to take risk. We are not going to touch any cargo that involves sanctioned entity or ships in the supply chain.”

—Indian refining official, Reuters, Feb. 13, 2025

Executive summary

Shadow tanker sanctions are forcing Russia to rely more heavily on the sanctions-compliant mainstream fleet.

With ceasefire negotiations at an impasse, policymakers will be seeking additional ways to increase economic pressure on Russia. Recent developments around the shadow fleet provide some fresh options. Large-scale tanker sanctions in 2025 have helped significantly reduce Russia’s shadow fleet capacity—down some 46%—without destabilizing energy markets (see Figure 1).

This, in turn, has forced Russian exporters to rely increasingly on sanctions-compliant mainstream tankers to ship their oil (see Figure 2). For Moscow, quickly restoring lost shadow fleet capacity is risky, expensive and impractical.

This provides policymakers with enhanced leverage for introducing new measures to restrict Russia’s all-important oil export revenues.

Moscow’s rising dependency on mainstream tankers provides policymakers with enhanced leverage over Russia’s all-important oil exports.

Part 1 of this report examines how policymakers might use this leverage to pursue fresh options for further restricting Moscow’s oil revenues. These options include low-risk, high-impact measures that can reduce (a) the revenue per barrel realized by exporters and/or (b) overall volumes exported. Gaining control over Russia’s vital oil revenue stream would put further strain on Russia’s increasingly stretched war finances. It would also further sap Moscow’s confidence that time is on its side.

Part 2 of this report is a Russian shadow fleet “explainer” in the form of an FAQ. It aims to provide a concise, accurate profile of the fleet—its origins, function, and vulnerabilities—and to correct various misconceptions surrounding it.

About the author

The author worked for many years as an investment banker at Morgan Stanley and Bank of America Merrill Lynch, where he was a vice chairman. During his banking career, he advised companies and governments around the world and led numerous financings, including Russia’s largest ever corporate transaction. He received an undergraduate degree in Russian studies and a doctorate in history from Harvard and a masters in Middle Eastern languages from Oxford, where he was a Rhodes Scholar. He is a Center Associate at Harvard’s Davis Center and is currently conducting research on Russia’s energy economy. He is also writing a history of the Russian oil industry, from 1860 to the present, and its impact on civil society formation.

Table of Contents

Executive summary

Preamble: Russia’s ailing oil and gas sector

Part 1: Emerging Options for further constraining Russian oil revenues

Introduction: Russia’s growing dependency on mainstream tankers

Background: the Kremlin’s flawed shadow fleet strategy

Solutions: new options for restricting Russia’s oil revenues

Part 2: Russian Shadow Fleet FAQ

Preamble: Russia’s ailing oil and gas sector

The health of Russia’s all-important oil and gas industry is steadily deteriorating under the strain of sanctions, heavy taxation, and strategic mismanagement.

Since the 1960s, Russia has relied on oil exports to the West to fund its military industrial complex. By the late 1980s, however, excessive taxation, poor strategic management and loss of access to western technology helped send Soviet Russia’s oil sector into steep decline.

While we are likely far away from a collapse of that magnitude, those same forces are at work again today—steadily degrading the health of Russia’s oil sector along with its war-funding capacity. Sector updates for Kremlin officials must make for grim reading.

Consider, for example, the litany of bad news from the oil sector:

production costs are up and field productivity down, as Russia’s reserves of “easy” oil are progressively exhausted, while access to the advanced Western technology Russia needs for “difficult” oil is tapering off;

sanctions have blocked Rosneft’s massive $100 billion Vostok Oil development project from coming on stream;

refineries packed with high-end, Western equipment are suffering from lack of servicing and spare parts, not to mention a steady barrage of drone strikes;

tanker sanctions and attrition have sidelined shadow fleet vessels worth some $8.5 billion;

sanctions continue to cause Urals oil to be sold at far deeper discounts to benchmark Brent than was historically the case;

year to date, oil is averaging far below the 2025 budget’s Urals breakeven price of $69.97; and

industry investment budgets are being squeezed by higher taxes and lower revenues.

News from the LNG sector is no better:

sanctions have paralyzed Novatek’s high-profile, $25 billion Arctic LNG 2 project just as it was loading its first cargoes, undercutting Russia’s ambition to become a top-4 LNG supplier;

Yamal LNG’s $8 billion in annual sales to Europe could be phased out by 2027;

As for Gazprom, the company’s newly released 2024 financial results use accounting sleight-of-hand to boost headline profit numbers, while the cashflow statement shows a company that continues to lose money:

gas export revenues are down 64% from 2022 levels;

the company’s cash reserves fell by another $3.4 billion in 2024 (net of debt repayments);

with $69 billion in debt and facing record-high interest rates at home, the company spent $7.7 billion in interest alone in 2024—most of which appears to have been booked as a capital expense, thus boosting headline profit figures;

burdened with a large, regulated domestic business, Gazprom’s gas division still appears to be suffering large negative cashflows. Gazprom now relies on its profitable oil division to stay afloat;

the company looks likely to continue losing money in 2025, off the back of lower oil prices and the termination of Ukraine transit volumes.

Though no Kremlin technocrat would dare say this out loud, many are surely thinking it. The Kremlin’s ill-judged weaponization of Gazprom’s exports to Europe decimated a business that took half a century to build. In doing so, it wiped out the main source of profit for what had been Russia’s largest taxpayer and most strategically important company. It’s hard to overstate the self-harm caused by this reckless blunder.

While the industry is unlikely to collapse, sanctions are weakening its ability to perform its dual roles of (i) funding the war-budget and (ii) driving the broader economy.

This isn’t to suggest that Russia’s energy industry will collapse tomorrow. It’s built for stress. But so long as the industry lacks access to the holy trinity of (i) advanced Western energy technologies, (ii) cheap and abundant Western risk capital, and (iii) premium Western markets, the condition of the sector is likely to deteriorate further.

And this will steadily diminish the sector’s ability not only to fund Russia’s militarized budget, but to play its role as the engine of Russia’s broader war economy.

Because it’s not just the sector’s contributions to the state budget that make it so vital to Russia’s war effort. The hard currency generated by export oil sales helps facilitate Russia’s heavy reliance on imported materiel, equipment and components for the war. Its large domestic capital and operational budgets have an expenditure multiplier effect. And both Gazprom and the Russian oil majors are obliged to provide domestic consumers with cheap, below-market energy—which amounts to a hidden tax that can be worth tens of billions of dollars a year.

In one critical area—oil export revenues—sanctions have fallen far short of their potential. Recent developments, however, provide Western policymakers with new options for further restricting oil revenues.

While sanctions have done much to help degrade the oil and gas sector’s war-funding capacity, there is one critical area where sanctions have fallen well short of their potential: reducing oil export revenues. Recent developments around the shadow fleet, however, offer policymakers some new options for stepping up the pressure on Russia’s all-important oil revenues. This report reviews those developments and outlines these options.

Overview of report

Part 1: New options for further constraining Russian oil revenues

Part 1 of this paper analyzes recent shipping data showing that tanker sanctions have sidelined a large number of Russian shadow tankers, substantially reducing the fleet’s usable capacity. That drop in capacity, in turn, has compelled Russian exporters to rely more heavily on sanctions-compliant mainstream tankers—giving policymakers enhanced leveraged over Russia’s oil export revenues. The paper then outlines how policymakers might use their improved leverage to further restrict Russia’s oil revenues. Options include pragmatic, low-risk, high impact measures that can restrict either the revenues exporters can earn per barrel and/or the volume of barrels they are able to export.

Part 2: Shadow Fleet FAQ—dispelling misconceptions

Part 2 provides an “explainer” about Russia’s shadow fleet in the form of an FAQ. It aims to provide a concise, accurate profile of the fleet—its origins, function, and vulnerabilities—and to correct various misconceptions surrounding it.

Part 1: New options for further constraining Russian oil revenues

Introduction: Russia’s growing dependency on mainstream tankers

The sharp drop in Russian shadow fleet capacity following Q1 tanker sanctions has forced Russian exporters to rely more heavily on sanctions-compliant mainstream tankers.

Since mid-January, there has been a significant shift in oil export patterns out of Russia. For certain key export streams—most notably the high-volume flow of crude out of the Baltic—the share of Russian shadow fleet tankers has been falling sharply (see Figure 3). In the second half of 2024, shadow vessels accounted for over 60% of the crude tankers loading at Russia’s Baltic terminals. By the end of March 2025, this had abruptly plunged to below 40%. Filling the gap has been a surge in loadings by mainstream crude carriers.

The collapse in shadow fleet loadings is not the result of Urals prices dropping below the $60 price cap level; the plunge was already well underway before quoted prices fell beneath the threshold. Rather, it’s the result of the abrupt and sizeable loss of usable shadow fleet capacity in the wake of OFAC’s January 10th jumbo tanker sanctions, which targeted some 158 oil tankers. It was helped along by additional tanker sanctions by the UK and the EU at the end of February.

All told, this recent round of jumbo sanctions—along with earlier sanctions and attrition—have reduced the overall capacity of Russia’s shadow fleet by some 46%. Thus, to keep exports whole on tonnage intensive export streams—like Baltic crude—Russian exporters have been forced to rely more heavily on the sanctions-compliant mainstream fleet. Falling oil prices have simply helped get risk-averse mainstream operators more comfortable re-entering the Russian trade. But risk-friendly mainstream operators have been in the Russia trade since sanctions were introduced.

This increased dependency on Western shipping capacity provides policymakers with new leverage over Russia’s oil export revenues

This rising dependency on mainstream shippers is actually a reversion to the status quo ante before the launch of Russia’s shadow fleet initiative in May 2022. If this reversal can be maintained and further advanced, it opens up fresh opportunities for policymakers to put pressure on Russia’s oil export revenues.

Before examining those opportunities, it’s important to understand why tanker sanctions have been effective and how policymakers can enhance that efficacy.

Background: the Kremlin’s flawed shadow fleet strategy

The Kremlin hastily improvised its shadow fleet strategy in the Spring of 2022 when it belatedly realized its vulnerable oil export supply chain was at risk of sanctions.

The global oil trade is structured around a range of critical services in which Western countries play a central role. These include shipping, trading, finance and insurance.

For decades prior to 2022, Russia relied heavily on this ecosystem of services for practically all its seaborn oil exports. It was convenient, competitively priced and efficient.

This heavy reliance on Western service, however, left Russia’s oil export supply chain highly exposed to potential Western sanctions. Prior to 2022, however, Moscow showed little concern over this risk. While it toiled to safeguard its banking and other sectors from sanctions, no new initiatives were taken to safeguard its oil export supply chain. The Kremlin appeared to think Russia’s oil exports were so vital Western economies as to be sacrosanct; Western policymakers would never dare impose sanctions regardless of Moscow’s transgressions.

This illusion was punctured in weeks immediately following Russia’s February full-scale invasion of Ukraine, as select Western service providers and importers began voluntarily shunning Russian oil exports. In parallel, European public opinion quickly shifted in support of sanctions on Russian oil.

This strategy aimed to reduce Russia’s sanction exposure by building out a parallel oil shipping ecosystem free from reliance on Western services.

The Kremlin quickly realized its complacency had been ill-judged. In May, it announced a hastily improvised strategy to protect its exports from supply chain risk by building out its own, Russian-controlled export ecosystem (see Figure 4). This initiative involved a scramble to develop its own, stand-alone capabilities in finance, trading and maritime insurance.

Its centerpiece is a Russia-dedicated shadow fleet that is free from Western ties and mistakenly believed to be immune to Western sanctions.

The centerpiece of this strategy was the creation of a large, proprietary tanker fleet—commonly called the Russian “shadow fleet.” Tankers in this fleet would have two distinguishing features: (i) they would be fully dedicated to the Russia trade; and (ii) they would be free of any commercial ties to critical Western services, such as hard-to-arrange spill-liability insurance. This, it was mistakenly thought, would render them immune to Western sanctions pressure. They could carry cargoes in contravention of sanctions without fear of losing access to sanctions-compliant Western critical services, such as financing or insurance.

A fleet of over 500 exporting vessels was eventually assembled, including nearly 100 tankers from Russia’s pre-existing state fleet and over 400 tankers bought second-hand at an estimated cost of $14 billion.

The shadow fleet initiative immediately ran up against the challenge of scale. Russia accounts for roughly 10% of oil exports by producer countries. Its tanker capacity needs are very large. How would it source enough vessels that were free of ties to Western service providers?

Russia’s shadow fleet would end up being comprised of tankers from two distinct groups. The first group were tankers already belonging to Russian companies—principally Russia’s state-owned shipping company, Sovcomflot (“SCF”). These amounted to nearly 100 tankers, and they form the core of the Russian shadow fleet.

The second group of tankers came from acquisitions in the used tanker markets. In the three years since May 2022, more than 400 tankers have steadily been acquired second-hand—mostly from mainstream fleets via intermediaries it appears (see Figure 5). Once acquired, these tankers would be scrubbed of any commercial ties to Western companies—most notably, spill liability insurance. They are then put to work full time on the Russia trade. The estimated acquisition cost to date: around $14 billion, based on comparable transaction analysis.1

By the end of 2024, the legacy component of Russia’s shadow fleet accounted for some 20% of active capacity, with the recently acquired portion accounting for around 80% (see Figure 6).

It’s notable that relatively few tankers from the pre-existing “global” shadow fleet—which supports Iran and Venezuela—have entered the Russian shadow fleet. The chief barrier seems to be suitability. Many of those vessels are too large to load at Russian ports. Others, it appears, may be unwilling or unable to provide the high degree of commitment and reliability that Russia’s tightly balanced export system requires.

The flaw in Russia’s shadow fleet strategy: key importers, such as Indian refiners, are unwilling to cut ties with the mainstream oil trading ecosystem

Russia’s parallel supply-chain strategy turns out to suffer from one major flaw: major importers—like Indian refiners—weren’t prepared to sever their ties with the mainstream oil trading ecosystem (see Figure 4 above). They were happy to buy Russian oil above the price cap and to have those cargoes delivered by shadow fleet tankers—but not if it meant jeopardizing access to valuable advantages only available in the mainstream oil market. These include hard-to-replicate services and features such as:

low-cost, quality spill-liability insurance for their massive product export businesses,

U.S. dollar accounts for settlements,

access to the London derivatives markets, and

the ability to export products to Europe—Indian refiners’ largest export market.

Unwilling to put their access to mainstream services at risk, major importers are refusing to accept cargoes on sanctioned tankers.

This flaw in Russia’s strategy was made apparent in October 2023, when OFAC started a limited, 5-month campaign of direct sanctions on Russian tankers. Some 40 vessels were targeted. Each was soon sidelined, when importers refused to accept cargoes transported by a sanctioned vessel. Over the summer of 2024, the UK and the EU joined in with a phased campaign of tanker sanctions.

Consequently, tanker sanctions have been broadly effective and have helped reduce Russian shadow fleet capacity by 46%.

It wasn’t, however, until January 2025, that Western authorities issued a sanctions list expansive enough to sideline critical mass of Russian shadow fleet capacity. That’s when OFAC sanctioned some 183 vessels working the Russian energy trade, 158 of which were oil tankers. Analysis of shipping data through the end of March 2025, shows that the January OFAC listings, along with earlier tanker sanctions and some general fleet attrition, have reduced active Russian shadow fleet capacity by some 46% (see Figure 7).

The jumbo Q1 2025 tanker sanctions demonstrated that large numbers of tankers could be targeted at once without destabilizing markets.

Some observers had feared that sanctioning a very large number of Russian shadow tankers all at once could significantly disrupt the global energy markets. A collapse in Russian shadow fleet capacity might cause a sudden and severe drop in Russian export volumes or a prolonged increase in freight rates.

But those scenarios didn’t materialize. What did happen, however, is that mainstream tankers expanded their loadings in Russia to fill the void left by sidelined shadow tankers—as mentioned at the outset (see Figure 3 above).

The Q1 2025 sanctions mark an important inflection point in efforts to restrain Russia’s oil export revenues. They are proof of concept that tanker sanctions can sideline a large portion of the shadow fleet in one go without destabilizing the markets.

Solutions: new options for restricting Russia’s oil revenues

Western authorities have “cracked the code” on rolling back the shadow fleet at scale. This opens new options for restricting Russia’s oil revenues.

In effect, sanction authorities have “cracked the code” on how to roll back the shadow fleet at scale. In the process, they are compelling Moscow to become increasingly reliant once more on sanctions-compliant Western shipping services. This provides policymakers with enhanced leverage over Russia’s all-important oil exports, which opens up new options for restricting Russia’s oil revenues.

How might Western policymakers take advantage of this enhanced leverage? A potential program could look like this.

Step 1: further enhance leverage through a follow-on, large-scale round of tanker sanctions: increase dependency on Western services by further reducing active shadow fleet capacity. Policymakers might achieve this by imposing another large-scale round of sanctions on par with OFAC’s January listing; this could push dependency levels on the mainstream fleet to over 90% from key ports.

Rolling back the rest of the shadow fleet would have the additional benefits of (a) reducing environmental risk along coastlines around the world and (b) opening up more commercial opportunities for shipowners that invest the care and expense into observing international standards and regulations.

Step 2: discourage reconstitution of the shadow fleet: dissuade Moscow from attempting to rebuild its shadow fleet, by clearly signaling that any additional shadow tankers introduced into the Russia trade are at risk of being sanctioned;

Step 3: implement revenue restricting measures: introduce one or more of these value- and volume-restrictng measures:

Value-constraining measures: these are measures aimed at reducing the net revenue per barrel received by exporters.

Lower the price cap. This uses the existing price cap mechanism. With most Russian oil shifted back onto mainstream tankers, a drop in the price cap might prove effective. But it might also still be vulnerable to price attestation fraud, if bad actor traders are providing shipowners false information.

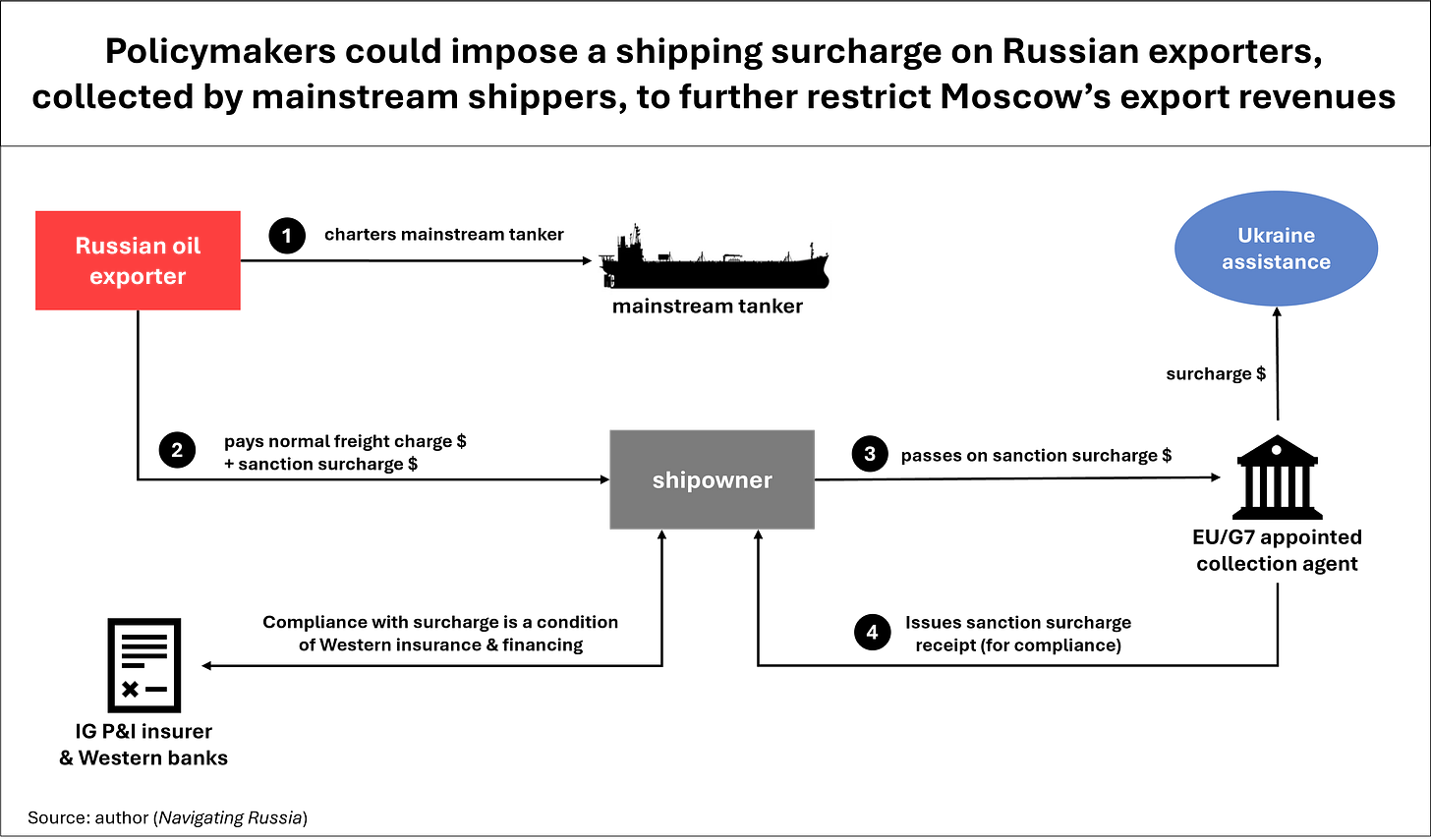

Impose a freight surcharge. This could be a more transparent and effective measure than the price cap. Mainstream tankers lifting from Russia would be obligated by policymakers to impose a special sanctions “freight surcharge” on top of their normal freight rates; they would then remit this surcharge to a collection agent bank appointed by policymakers (see Figure 8). Proceeds could help fund Ukraine defense and reconstruction.

Mainstream shipowners—regardless of where they are domiciled—would need to comply with the sanctions surcharge obligation as a condition of maintaining access to EU/G7-based marine insurance, ship mortgages and other critical services. (Mainstream fleet owners operating in Russia continue to show very high levels of commitment to Western based spill liability insurance.) Russian exporters would ultimately bear the cost of this surcharge, since it could not be passed on to importers in the highly efficient oil markets. A surcharge of $15 per barrel could, for example, transfer some $25 billion a year from Russian exporters to Ukraine.

Volume-targeted options: these options aim to reduce Russian revenues by curbing Russian export volumes. Given Russia’s significance in the global oil markets, any volume-related measures need to be carefully calibrated to avoid counterproductive market disruptions. Today’s soft oil markets provide a relatively low-risk environment in which to pare back Russian export volumes.

Recently, sanction authorities have tried to curb Russian export volumes by sanctioning specific producing companies. This, however, has had little noticeable effect on overall export volumes. That’s, in part, because the beneficiary ownership of most export barrels can be relatively easily obscured onshore, before they are presented for export.

Impose loading bans at specific terminals. An alternative way to curb export volumes would be to ban mainstream tankers from lifting oil from specific Russian export terminals. There are 18 or so major active terminals around Russia, with limited options for shifting capacity from one terminal to another. Policymakers could decide what portion of Russian export volumes to remove from the market and configure terminal bans to meet those aims.

Mainstream tankers would avoid lifting cargoes from banned terminals. Shadow tanker capacity would be too diminished to manage loads out of the banned terminals, leaving export barrels stranded on shore. As storage facilities are overwhelmed, Russian producers would be compelled to shut in some of their production.

Targeting flows from specific terminals has several potential advantages over targeting production from specific companies:

it’s far easier for sanctions authorities to monitor where oil is loaded than where it is produced, limiting options for evasion through falsifying origin;

shippers have greater clarity over what is and is not permitted oil; and

it also offers the flexibility to dial up or down volumes as needed by adding or removing export terminals from the list.

Conclusion: rolling back the shadow fleet and diminishing Moscow’s control over its oil exports will further undermine the Kremlin’s confidence that time is on its side.

Maintaining control over its oil export revenues remains a strategic priority for Moscow. They are critical for funding an increasingly expensive war without having to resort to the problematic options of heavier borrowing or more tax hikes. Hence, the extraordinary effort and expense Moscow has invested into its shadow fleet strategy. But as with other major Kremlin initiatives, this strategy has turned out to be fundamentally flawed.

Western policymakers now have an opportunity to sideline Russia’s shadow fleet entirely. In doing so, they can gain significant sway over Russia’s oil revenues and exert further pressure on Moscow’s stretched wartime finances. What’s more, it would weigh on Russia’s war calculus by sapping the Kremlin’s confidence that time is on its side.

Part 2: Russian Shadow Fleet FAQ

What is the Russian shadow fleet?

When and why did Moscow develop its shadow fleet strategy?

What are the key distinguishing features of a Russian shadow fleet tanker?

Where did Russia source the tankers in its shadow fleet?

Why have so few Russian shadow fleet tankers been sourced from the “global” shadow fleet?

What happens when a tanker is acquired for Russia’s shadow fleet?

When was Russia’s shadow fleet acquired?

Who owns Russia’s newly acquired shadow tankers?

How much has Russia’s shadow fleet cost to assemble?

How does the shadow fleet help Russia circumvent sanctions?

Does that mean the Russian oil export revenues have remained undiminished by sanctions?

What has been the impact of Western sanctions imposed directly on shadow fleet tankers?

Why are these tanker sanctions effective?

With the sharp drop in available Russian shadow fleet capacity, have exports cargoes been shifting back to the mainstream fleet?

Wasn’t it the drop in the Urals price that caused the surge in mainstream fleet loadings in Russia?

Won’t Russia just buy more tankers and convert them for use in the shadow trade?

So, up to now, has Russia’s shadow fleet been a clever strategy worth the high price tag? Or a flawed strategy that wasted scarce investments resources?

What is the Russian shadow fleet?

It’s a group of over 500 vessels—many currently inactive—that has been assembled under a May 2022 Kremlin directive aimed at reducing Russia’s considerable exposure to potential Western sanctions on its oil exports.

It’s helpful to think of these vessels as a “proprietary” or “dedicated” Russian fleet—something quite distinct both from (i) the global mainstream fleet and (ii) the pre-existing “non-Russian” or “global” shadow fleet that has long serviced sanctioned regimes, such as Iran.

When and why did Moscow develop its shadow fleet strategy?

Moscow hastily devised its shadow fleet strategy in May 2022, when its long-held assumption that the West would never sanction Russian oil exports turned out to be ill-founded.

For decades, Russia has relied almost entirely on Western companies—shippers, insurers, traders, banks—to manage its seaborne oil exports. And most of those exports went to Western buyers (see Figure 9).

After the initial round of Russia sanctions in 2014, Moscow launched no new initiatives to reduce this dependency. The Kremlin appeared confident the West would never dare sanction Russian energy exports, regardless of Moscow’s transgressions.

In the weeks immediately following the February 2022 invasion, however, that confidence was shattered. Western companies involved in the Russia oil trade temporarily suspended operations to review legal and reputational risks. Export volumes collapsed, Russia’s limited storage capacity was quickly overwhelmed, and producers were forced to shut in 1 million barrels a day in output (see Figure 10).

Exports soon resumed, but the episode was a wake-up call for the Kremlin: it had misjudged Western tolerance, leaving Russia’s oil revenues seriously exposed. That risk became more elevated over the course of April, as news of Russian war atrocities increasingly turned European public opinion in favor of sanctioning Russian oil.

The Kremlin hastily improvised a plan, which Putin announced in May. Russia would undertake to create a Russian-controlled oil-export supply chain separate from the mainstream supply chain. And at its core would be a vastly expanded, Russian-controlled tanker fleet—one not reliant on Western maritime services and fully dedicated to the Russia trade.

What are the key distinguishing features of a Russian shadow fleet tanker?

To determine whether a tanker belongs to Moscow’s proprietary shadow fleet, it’s usually sufficient to look for two distinguishing markers:

is the vessel dedicated to the Russia trade, only handling Russian cargoes?

does it carry spill liability insurance issued by the Europe-based International Group of P&I Clubs (“the IG”)?2

If the answers are “yes” and “no” respectively, then there’s a very high likelihood that the tanker in question is part of Moscow’s proprietary fleet. When a tanker meets these two qualifications, further examination usually reveals additional telltale signs concerning changes in ownership history (see below: “What happens when a tanker is acquired for Russia’s shadow fleet?”).

Other markers, such as flagging, country of registered ownership, subterfuge activities—like spoofing—are far less indicative of membership in Russia’s shadow fleet.

Where did Russia source the tankers in its shadow fleet?

Russia’s shadow tankers come from two main sources (see Figure 11):

The core of Russia’s shadow fleet consists of close to nearly 100 tankers that were owned by Russian companies prior to 2022, principally Russia’s state-owned Sovcomflot.

Nearly all the rest—over 400 vessels—have been steadily acquired since May 2022 through purchases in the second-hand tanker market. Most have been bought from mainstream fleets selling off their aging assets. (These sales appear to often be conducted in back-to-back transactions involving third parties).

Consequently, when profiling a tanker lifting from Russia, if the vessel lacks an IG spill liability policy (see the previous question), a review of its ownership history will usually reveal either (a) the vessel at some point was owned by Sovcomflot or another Russia-based shipowner, or (b) that the vessel has been sold at some point since May 2022. Further examination usually reveals that at the time of sale, the vessel dropped its IG policy and began regularly lifting cargoes from Russia.

Contrary to early expectations, only a small fraction of the tankers active in the Russia shadow trade have crossed over from the “global” shadow fleet.

Why have so few Russian shadow fleet tankers been sourced from the “global” shadow fleet?

Many of the tankers in the “global” shadow fleet don’t appear to be suitable for Russia’s specific needs. Some are VLCC class tankers, which are too large to load at Russian terminals. Others simply appear unable or unwilling to provide the levels of commitment and reliability Russia’s tightly balanced export system requires.

What happens when a tanker is acquired for Russia’s shadow fleet?

To make a newly acquired tanker fit for service in the Russian shadow fleet, it needs to be scrubbed of any commercial ties to Western service providers. Such ties make it vulnerable to price-cap sanctions.

First and foremost, that means cancelling the vessel’s European-based spill liability insurance. Such insurance is mandatory under international regulations, however, so alternative arrangements must be made. Sometimes, these consist of opaque, dubious policies issued by Russian insurers. In other cases, insurance arrangements appear to have been entirely fraudulent.3

Additionally, ownership gets structured through anonymous shell companies in various low-transparency offshore jurisdictions. Vessels are also often reflagged to national registries with a reputation for lax enforcement of global shipping standards and regulations.

When was Russia’s shadow fleet acquired?

Russia’s shadow fleet has been steadily acquired over the last three years (see Figure 12. The highest concentration of purchases happened in Q4 2022 and Q1 2023, as the price cap was coming into force.

Who owns Russia’s newly acquired shadow tankers?

Ultimate beneficiary ownership cannot be determined based on public information. Various data points—acquisition patterns, commercial and technical managers, reflaggings, etc.—along with other information suggest ownership is likely distributed among a wide range of companies and investments groups that are either Russian or Moscow-friendly. All are likely to be working closely in league with the Russian state. As common in state-capitalist systems, the line between state and private sector activity is often blurred.

How much has Russia’s shadow fleet cost to assemble?

Estimated acquisition costs since May 2022 come to around $14 billion, based on comparable market transaction analysis. Many of these acquisitions have likely been financed with state-directed concessionary loans

As for Russia’s legacy fleet, most of these vessels were acquired as new builds more than a decade ago. Estimated current market value of the legacy fleet on a like-for-like basis comes to around $3.5 billion.

How does the shadow fleet help Russia circumvent sanctions?

Russia’s shadow fleet strategy circumvents sanctions by avoiding reliance on Western service providers in the export supply chain, rather than concealing the origins and destinations of their cargoes.

Contrary to much reporting, Russia’s shadow fleet doesn’t rely primarily on subterfuge to evade sanctions. Most don’t routinely manipulate their AIS signals (“spoofing”) or engage in “dark” ship-to-ship transfers.

That’s because concealment isn’t required to evade most of the current Russian oil sanctions. Until very recently, Russian oil sanctions have mostly focused on value, not volume. They aim to constrain the value-per-barrel that Russia gets for its oil, rather than reduce the overall volume of exports. That is the explicit aim of the price-cap—to limit value. And price-cap related sanctions were mostly primary in nature—they only applied to companies based in the sanctioning states.

Accordingly, Russia’s circumvention strategy has involved creating a parallel supply chain/export ecosystem that doesn’t rely on any critical Western services (see Figure 13). By avoiding any reliance on Western services—so the thinking went—Russia’s shadow tankers could openly ship cargoes priced above the cap and importers could safely purchase them.4

(In January, however, OFAC sanctioned two specific oil companies, Gazprom Neft and Surgutneftegaz. This has created an incentive for concealment that may prove—in some cases—to be counterproductive. As argued elsewhere in this report, export terminal bans may be a more effective means of restricting export volumes).5

Does that mean the Russian oil export revenues have remained undiminished by sanctions?

No. Western sanctions have significantly reduced Russia’s oil export revenues—by many tens of billions of dollars since late 2022. Nonetheless, it’s fair to say that sanctions have fallen far short of their potential for limiting Russia’s export earnings, while avoiding counterproductive market disruptions.

To date, Russian oil export sanctions have targeted value, rather than volume. They have sought to reduce how much Russia receives per barrel on its exports. A simple way to observe the impact that sanctions have on value is by tracking the discount at which Urals grade crude trades relative to benchmark Brent. Historically, Russian exporters could sell Urals at port in the Black Sea or the Baltic—on an “FOB” basis—for a $1 to $2 per barrel discount to Brent. The buyer would then pay for freight and insurance.

Since 2022, however, the Urals discount has exploded, ranging from $10 to $40 per barrel (see Figure 14). What’s caused it to widen so? Two things.

First, there is the EU/G7 ban on Russian oil. Historically, the largest market by far for Russian oil exports was nearby Europe. Most of Russia’s pipeline, and export terminal infrastructure—even many of its refineries—were developed with the aim of facilitating sales to Europe (see Figure 9 above).

The import ban, however, has forced Russian oil to travel much further to market, pushing up freight costs and pushing down FOB prices—which are net of freight. To make matters worse, the import ban means Russia must now sell into a smaller pool of demand. This weakens Russia’s bargaining power, forcing it to offer significant discounts, especially to very large buyers like India.

Second, the price cap figures in as well. A significant amount of Russian exports have continued to be transported by sanctions-compliant mainstream tankers. There is evidence that Russian exporters have managed to hire mainstream tankers to carry cargoes priced above the cap by providing fraudulent attestations about the price of their cargoes. Nonetheless, the heightened risk that mainstream tankers assume when lifting oil out of Russia has likely contributed to a “Russia risk” premium that mainstream shippers price into their freight charges, especially when reported market prices are above the price cap.

What has been the impact of Western sanctions imposed directly on shadow fleet tankers?

On the whole, direct tanker sanctions have been effective, although their impact has been lessened by long delays and—some would argue—an excessively restrained approach. In October 2023, OFAC launched a measured campaign of tanker sanctions. It consisted of a series of small-scale listings phased over a 5-month period that ended up targeting some 40 shadow fleet tankers.

These direct sanctions proved highly effective in removing tankers from normal commercial service. Practically all targeted tankers stopped loading oil for export. The problem wasn’t effectiveness, but scale. These sanctioned vessels amounted to less than 15% of Russia’s then-active shadow fleet capacity. Additional purchases compensated for this loss.

In the summer of 2024, the UK and the EU also began directly sanctioning shadow tankers, which helped further disrupt Russian shadow shipping patterns.

It wasn’t, however, until January 2025, that direct tanker sanctions caused a major and sudden reduction in active shadow fleet capacity. That’s when OFAC resumed tanker sanctions with a jumbo listing that targeted over 180 vessels.6 In late February, the EU and the UK also issued substantial lists.

By late March 2025, some 46% of Russia’s proprietary shadow fleet had been effectively removed from normal commercial service (see Figure 15). That’s mostly the result of tanker sanctions, with attrition also accounting for a modest fraction.

Why are these tanker sanctions effective?

Tanker sanctions are effective, because many of Russia’s large oil-importing customers don’t want to receive oil shipped on sanctioned tankers. These importers value their access to mainstream oil trading ecosystem, and don’t wish to put that access at risk. Consequently, Russia has been forced to sideline most of its sanctioned tankers and provide “clean,” unsanctioned tankers when delivering to these customers.

This sidelining of sanctioned tankers reflects a fundamental flaw in Russia’s parallel supply-chain strategy (see Figure 13 above). Moscow managed to execute part of that strategy, but not all of it. It has managed to create several Russian-controlled links that are free from Western commercial ties, such as trading, shipping, and insurance. But it has failed to replicate the final, critical link: a set of major importers willing to sever ties with the mainstream oil trading ecosystem.

This is a critically important point. Russia’s biggest importers are Indian, Chinese and Turkish refiners. Most of these greatly value unfettered access to the mainstream oil trading ecosystem. That ecosystem is structured around a range of valuable Western based services that Russia’s own supply chain simply can’t offer—and many of Russia’s biggest customers simply don’t want to do without.

Take, for example, large Indian refiners. India is the world’s second largest refined product exporting country. To deliver their export cargoes to market, Indian refiners depend on tankers insured —and often owned—by European companies. Not only is Europe providing the shipping, it’s also the most prized and largest market for Indian product exports. To hedge risks, Indian refiners rely on the massive, London-based oil derivatives markets. And they rely on access to U.S. dollar accounts for settlement, since the global oil trade is dollar denominated.

So it was no surprise when, in February, India’s oil minister said it would not accept any Russian oil delivered on US-sanctioned tankers. As one official said: "We don't want to take risk. We are not going to touch any cargo that involves sanctioned entity or ships in the supply chain.”

With the sharp drop in available Russian shadow fleet capacity, have exports cargoes been shifting back to the mainstream fleet?

Yes, they have. The jumbo sanctions from Q1 2025 have sharply reduced the shadow tanker capacity available to Russian exporters. Rather than cut exports, they have been chartering more mainstream tankers.

This is especially evident among crude tankers loading in the Baltic. Crude exports from Russia’s Baltic terminals rely more heavily on shadow fleet tonnage than any other export streams. The loss of shadow tanker capacity has been especially pronounced here.

Consider the following. In the second half of 2024, less than 40% of the crude tankers loading at Russia’s Baltic ports were from the mainstream fleet. The shadow fleet averaged over 60%. By the end of March 2025, however, those ratios had reversed, the shadow fleet loadings plunging below 40% (see Figure 16).

Wasn’t it the drop in the Urals price that caused the surge in mainstream fleet loadings in Russia?

No. This argument confuses causality. Some commentators have incorrectly ascribed the increase in mainstream tanker loadings to the fall in the Urals price below the cap. The surge began well before Urals dropped below the cap. That’s because exporters faced a sudden drop in the availability of unsanctioned shadow fleet tonnage and opted to charter more mainstream tankers, rather than shut in production.

Throughout the period the price cap has been in place, mainstream tankers have been active in the Russia trade—even when quoted FOB prices were far above the price cap. They were allowed to do this under the sanctions rules, because they received attestations claiming their cargoes were priced at or below the cap. Many of these attestations may have been fraudulent, but that was a risk at least some mainstream operators were prepared to take—though not all.

Almost immediately after OFAC’s January 10 jumbo listing, a shortage of available, unsanctioned shadow tankers was felt along shadow-heavy export routes, in particular crude flows out of the Baltic. Risk-friendly mainstream tankers responded quickly to fill the void, and the resulting surge in mainstream loadings was already apparent in the second half of January (see Figure 16 above). That happened despite the Urals price remaining above the cap at that point. And throughout the second half of January, the quoted Urals price remained above the price cap.

As global oil prices dropped further in Feburary, Urals dropped below the cap. It’s at that point that more risk-averse operators among the mainstream fleet felt comfortable re-entering the Russia trade. And they have found demand for their services, because of the collapse in available unsanctioned shadow fleet tonnage.

Which raises an interesting question: if the price cap were dropped well below the current price (now in the low 50s), what would happen? Would enough risk-friendly mainstream operators remain to meet Russia’s needs without a further drop in the price? Or would Russia have to drop its prices to attract the more risk-averse mainstream operators?

Won’t Russia just buy more tankers and convert them for use in the shadow trade?

Probably not—at least not at anything like the previous scale. Assembling the shadow fleet was a very costly proposition, requiring hundreds of tankers to be purchased in the used markets over the course of the last 3 years. As noted above, an estimated $14 billion has been spent acquiring these vessels. The like-for-like market value of the sanctioned tonnage is approximately $8.5 billion based on past comparable transactions. Replacing those tankers by buying in the used market would almost certainly bid prices up even higher. So, this would be a slow and very costly process to begin with.

What’s more, the success of the Q1 jumbo sanctions in sidelining shadow tankers acts as a huge disincentive to investing more in the fleet. If Western authorities can render a tanker commercially unusable simply by putting it on a list, spending billions more in precious investment capital risks throwing good money after bad.

The same disincentives would also discourage shipowners from the “global” shadow fleet from chartering out their vessels into the Russia trade. If it carried a high risk of a direct sanction, many owners might prefer not to take the risk.

Much, however, depends on the posture of Western sanctioning authorities. If they continue to actively discourage importers from accepting cargoes shipped on these vessels, then Russia is unlikely to go on another used tanker shopping spree.

So, up to now, has Russia’s shadow fleet been a clever strategy worth the high price tag? Or a flawed strategy that wasted scarce investments resources?

On balance, Moscow’s shadow fleet appears to have been a flawed and costly strategy. A few of the vessels in the fleet—those working the short haul Pacific trade—have almost certainly been good investments. The ESPO oil price has traded far above the price cap, meaning each shadow tanker cargo captures significant margins above the cap. The short-haul routes to China mean a tanker can deliver many cargoes in a year.

But Russia’s Pacific trade requires only a fraction of the total tonnage needed to keep Russia’s exports flowing. Had Moscow simply maintained a small shadow fleet focused on that trade, it would almost certainly have been a lucrative investment.

The same can’t be said for the shadow trade out of the Baltic. Most of these tankers have been carrying Urals, which has often been below the price cap since December 2022 (see Figure 12). Shadow tankers working the Baltic-to-India route can take up to five times as long to complete a round trip as their Pacific counterparts. Most of these tankers have probably not generated enough additional above-price-cap revenue to justify their high price tags and hefty financing costs.

Worse still, many have had their commercial lives cut short by sanctions. Many of those vessels almost certainly have acquisition loans still outstanding, but no income stream with which to service these loans.

So, while a fraction of Moscow’s acquired fleet has generated very healthy returns on investment, the large majority have almost certainly been a waste of money on a large scale. That marks another failure in strategic thinking by Moscow’s often overhyped technocracy. Billions get spent on a fleet to circumvent sanctions when the fleet itself turns out to be highly vulnerable to direct vessel sanctions.

But then it’s worth recalling that these are the same people who complacently assumed that Western markets and service providers would continue to fully support Russia’s oil exports regardless of any transgressions by Moscow. That mistaken judgement—as we saw above—led to the March-April 2022 export crisis, which led the Kremlin to hastily improvise its shadow fleet strategy. And, thus, one strategic misjudgment led to another.

Disclaimer: No Advice

The author of this substack does not provide tax, legal, investment or accounting advice. This report has been prepared for general informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for tax, legal, investment or accounting advice. The author shall not be held liable for any damages arising from information contained in the report.

© Copyright 2025, by Craig Kennedy. All rights reserved.

Endnotes

In this report, statistics relating to tankers in the Russia trade exclude small vessels below 25,000 deadweight tons. They are immaterial to Russian export volumes. Fleet size is often expressed in terms of tonnage rather than vessel count. To make the tonnage figures relevant, they are expressed in terms of "Aframax class tankers”—the most common class of crude tanker loading in Russia. Unless otherwise cited, figures and estimates are based on the author’s analysis of relevant data sets.

The International Group of P&I Clubs is a not-for-profit mutual insurance association made up of shipowners from around the world, who pool resources to provide their club members with adequately levels of liability insurance on a cost-efficient basis. The IG provides “P&I” (protection and indemnity) insurance for some 90% to 95% of the global oil tanker fleet to help them meet international regulatory requirements for spill liability insurance. The IG generally meets high standards of transparency and capital adequacy. Because of the mutual nature of risk sharing, these club members are highly incentivized to enforce on one another high standards of compliance with international safety regulations. And because a large portion of the membership is based in EU/G7 countries, the IG observes EU/G7 sanctions policies. Nonetheless, state owned fleets from around the world, including China and India, insure through the IG; making legitimate, alternative arrangements entails expense, complexity and risk that these fleet owners aren’t apparently ready to take on.

There are some legitimate smaller insurers outside the IG that provide quality fixed-rate insurance for smaller tankers. But if a large tanker (above 50,000 deadweight tons) is not carrying an IG policy, it is fair to be sceptical about the quality of that policy. Their insurers often have very low levels of transparency. They often don’t provide quality third-party audits of their accounts and credit rating reports from recognized firms. They also often don’t provide public confirmation of which ships they are insuring. Such is the case with nearly all of Russia’s shadow fleet. This leads to valid questions over whether these policies meet the guidelines for capital adequacy issued by the IMO. In some cases, these insurance firms have turned out to be completely fraudulent—little more than a website and an office issuing fraudulent certificates.

Shadow tankers—both in the Russian and global fleet—often opt for these non-IG solutions, because they are likely less expensive—not just in terms of premia, but also by enforcing lower standards of regulatory compliance. Critically, shadow vessels may also take on non-IG coverage because the conditions of insurance don’t require compliance with EU/G7 sanctions. For more on insurance and the shadow fleet, see Craig Kennedy, Making the Baltic a “Shadow-Free” Zone, Brookings, May 2024.

For a further discussion of Russian shadow fleet insurance, see Craig Kennedy, Making the Baltic a “Shadow-Free Zone”, Brookings, May, 2024.

There is significant evidence suggesting Russian exporters have also managed to price cargoes above the cap even when using mainstream vessels. They have done this by providing shipowners with price attestations that fraudulently misstate actual pricing in order to comply with the price-cap conditions. For Moscow, relying on circumvention through attestation fraud carries the significant risk of more effective enforcement. Hence, the decision to invest massive resources into assembling a proprietary fleet.

In January 2025, OFAC sanctioned the exports of two Russian oil companies, Gazprom Neft and Surgutneftegaz. As with most oil produced in Russia, much of the crude produced by these companies must be transported through the Transneft main trunk pipeline system en route either to a refinery or to an export terminal. When crude is sent through the Transneft system, it is blended, no batched. That is to say, Transneft mixes crude from hundreds of producing fields that feed into the Transneft system. So, the molecules producers put into the system are not the same ones that take out. This makes it easier to obscure the origins of cargoes being lifted at port using on-shore means, such as pass-through companies, swaps, fraudulent paperwork and the like. It’s entirely impractical for shippers to accurately determine original beneficiary ownership of a cargo if the Russia side wanted to obscure this. That’s made easier by the fact that these two companies together account for less than 30% of Russia’s production. Rebranding their exports would be easy. Consequently, there is no need for shipping subterfuge, since the cargoes appear to be legitimate.

There are, however, certain export terminals where obscuring ownership is far harder. One of these is Murmansk. It’s outside of the Transneft system, and most of the oil exported from Murmansk comes from Gazprom Neft fields in the Arctic region. Consequently, using on-shore methods to obscure the origin of crude being lifted out of Murmansk is not practical. So, it’s not surprising that we’ve begun to see a major uptick in on-the-water subterfuge in recent weeks by tankers lifting at Murmansk. Worse still, the situation has created an opportunity to reactivate sanctioned tankers that had been laid up for months. These tankers have been making their way out of their long-term anchorages in the Gulf of Finland, turning off their beacons well before reaching Murmansk, reappearing on the AIS system heading south somewhere in the North Sea, but now laden with oil. Typically, they head East of Suez and, as they are entering the Gulf of Aden, they switch off their beacons again—only to reappear many days in ballast, having transferred their cargo somewhere between the Gulf of Oman and the Riau Archipelago.

This activity can and is being observed through satellite surveillance. Some of these cargoes appear to be heading to certain risk-friendly, private buyers in China that also purchase smuggled cargoes from Iran. But the size of this risk-friendly buyer universe is limited. Many large importers will be reluctant to import oil of dubious origin that may have been produced by a sanctioned company and transported on a sanctioned vessel. That’s certainly the case if sanctions authorities are being assertive with enforcement measures.

Most of this list included tankers routinely lifting oil from Russian ports. But it also included a handful of (a) newbuilds that had not yet been commissioned and (b) auxiliary vessels that operate either solely within Russia—going from remote fields to export terminals—or outside of Russia, providing floating storage or shuttle services along Russia’s main shipping routes.

An interesting piece, and the idea of the $15/bbl surcharge to go to a fund for Ukraine seems much better than any proposal to reduce oil output. That charge, however, to be collected by shippers, will continue to incentivize the shadow fleet. Alternatively, would it be possible to impose the surcharge on refiners; i.e., allow any refiner in the world to import Russian crude as long as it paid $15/bbl into a Ukraine reconstruction fund? This would eliminate the rationale for the non-seaworthy shadow tankers.

Enforcement of a penalty on refiners could be more complicated, but as noted by the quote from an Indian refiner, the prospect of being frozen out of financial markets could provide a compelling rationale. Moreover, despite the many problems of the current Administration's tariff policies, the President's threat to impose secondary tariffs on Russian oil could contain the kernel of a rationale policy. For example, if an Indian or Chinese refiner failed to pay the surcharge, complying countries could impose a secondary tariff on any oil product, petrochemical or plastic imported from those companies (or countries).

The West needs to incorporate the amount of war reparations, to be paid by Russia, into the negotiations to end this conflict. Iraq's reparations for the First Gulf War, paid through oil revenues, is a model.

An excellent and extremely informative article! Thank you.