Russia’s Hidden War Debt

Moscow has been stealthily funding much of its war costs with risky, off-budget financing overlooked by the West. That funding is now under pressure, offering new leverage to Ukraine and its allies.

*******

UPDATE, February 14, 2025: The full report—including updated numbers—has now been published on Navigating Russia and can can be found at: Russia’s Hidden War Debt (full report).

*******

[Below is the draft Executive Summary from a forthcoming report entitled Russia’s Hidden War Debt. The full report is expected to be published in the coming days on Navigating Russia.]

Moscow has been stealthily pursuing a dual-track strategy to fund its mounting war costs. One track consists of the highly scrutinized defense budget, which analysts have routinely deemed “surprisingly resilient.” The second track—largely overlooked until now—consists of a low-profile, off-budget financing scheme that appears equal in size to the defense budget. Under legislation enacted on the second day of the full-scale invasion, the Kremlin has been compelling Russian banks to extend preferential loans to war-related businesses on terms set by the state. Since mid-2022, this off-budget financing scheme has helped drive an unprecedented $415 billion surge in overall corporate borrowing. This report estimates that $210 to $250 billion of this surge consists of compulsory, preferential bank loans extended to defense contractors—many with poor credit—to help pay for war-related goods and services.

Initially, this off-budget defense financing scheme proved advantageous to Moscow by enabling it to maintain its official defense budget at manageable levels. That misled observers into concluding—incorrectly as it turns out—that Moscow faces no serious risks to its ability to sustain funding its war. More recently, however, Moscow’s heavy reliance on its off-budget, compulsory lending scheme has begun to cause serious, adverse consequences at home. Not only has it become the main driver of inflation and interest rate hikes, but it is also creating the preconditions for a systemic credit crisis.

In late 2024, the Kremlin became increasingly aware that its off-budget funding scheme is unleashing potentially disruptive systemic financial risks, such as prohibitively high interest rates, liquidity and reserve problems at banks, and a severely compromised monetary transmission mechanism. For Moscow, credit event risk—with its seismically disruptive potential—will be of far more immediate concern than slow-burn risks like declining GDP. Moscow now faces a dilemma: the longer it puts off a ceasefire, the greater the risk that credit events—such as corporate and bank bailouts—uncontrollably arise and weaken Moscow’s negotiating leverage. Moscow’s emerging financing dilemma is likely to weigh on its war calculus and offers unexpected negotiating leverage to Ukraine and its allies. This report details ways well-informed negotiators can exploit Moscow’s growing financial vulnerability.

Executive Summary

This report examines Russia’s strategy for funding its war on Ukraine. It assesses Russia’s ability to sustain elevated war-time expenditures and identifies vulnerabilities that can be exploited by Ukraine and its allies.

It has three key findings:

1) The Russian state has been pursuing a two-track strategy to cover its mounting war costs, supplementing its highly scrutinized defense budget expenditures with funding from an off-budget defense financing scheme that is similar in scale, but has been overlooked by analysts;

2) Unlike its federal defense budget expenditures, which remain at sustainable levels, Russia’s off-budget funding scheme is proving much more problematic to sustain;

3) This now poses a funding dilemma for Moscow that could weigh on its war calculus, while providing Ukraine and its allies valuable, new negotiating leverage; this report details ways to exploit Moscow’s growing financial vulnerability.

What follows is a summary of each of these three findings.

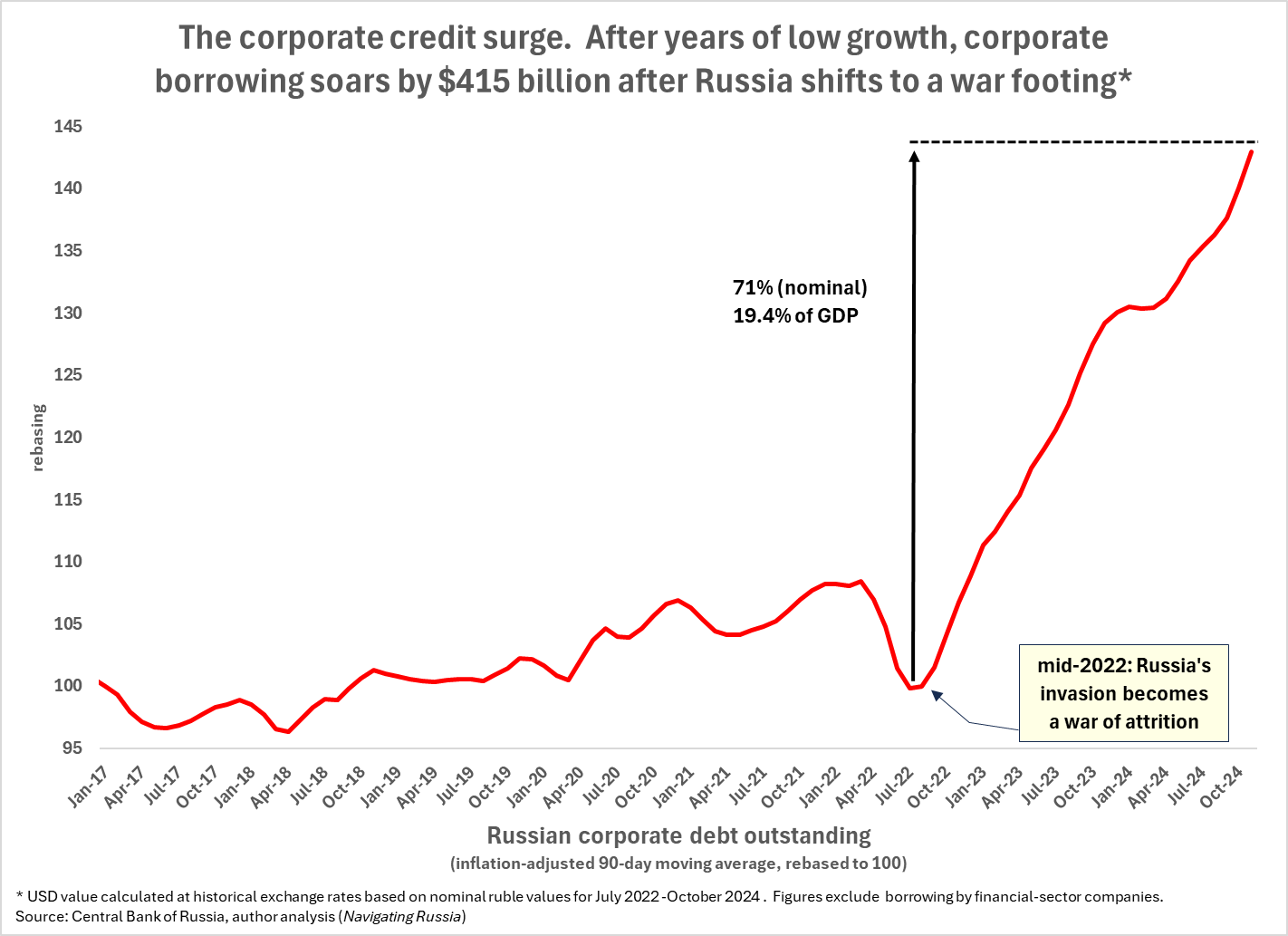

1)The Russian state has been pursuing a two-track strategy to cover its mounting war costs, supplementing highly scrutinized defense budget expenditures with funding from an off-budget financing scheme that is of similar scale, but has been largely overlooked.This off-budget funding stream is authorized under a new law, quietly enacted on February 25, 2022, that empowers the state to compel Russian banks to extend preferential loans to war-related businesses on terms set by the state.Since mid-2022, Russia has experienced an anomalous 71% expansion in corporate debt, valued at $415 billion or 19.4% of GDP (see Figure 1).

This incremental corporate credit surge is large compared to key budget metrics (see Figure 2). It significantly exceeds both total oil and gas revenues and defense budget expenditures over the same period and is 6.5x times larger than incremental government borrowing.

According to analysis of sectoral lending data, over 70% of the corporate credit surge went to sectors engaged in war-related activity (see Figure 3).

Not all lending to these sectors has necessarily been going to fund goods and services for the war. Based, however, on analysis in this report, it is estimated that between 50% and 60% of the wartime corporate credit surge ($207 to $249 billion) has gone to fund war-related business under the government’s off-budget funding scheme. These are loans that the state has compelled banks to extend to largely uncreditworthy, war-related businesses on concessionary terms. At this scale, Russia’s off-budget funding stream roughly equals total expenditures flowing through the federal defense budget.

Between 2010 and 2022, the Kremlin used a similar off-budget financing scheme—though on a smaller scale—with the express aim of surreptitiously supplementing funding for its costly rearmament program while appearing publicly to maintain budget discipline. The current scheme achieves a similar goal of allowing official budget spending to remain at sustainable levels, creating a misleading impression about the resilience of Russia’s war-funding capacity.

In short, Russia’s total war costs far exceed what official budget expenditures would suggest. The state is stealthily funding around half these costs off budget with substantial amounts of debt by compelling banks to extend credit on “off-market” (non-commercial) terms to businesses providing goods and services for the war.

2) Unlike the defense budget, which has been maintained at sustainable levels, Russia’s off-budget defense funding scheme became much more problematic to sustain during the second half of 2024; it has grown so large that it is driving inflation, pushing up interest rates for “real” economy borrowers to well above 21% and creating the preconditions for a systemic credit crisis. In the second half of 2024, the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) began identifying the state’s preferential corporate lending scheme as a significant threat to Russia’s economic stability. As the main contributor to monetary expansion, it has been driving Russia’s rising inflation. Worse still, because this lending is strategic rather than commercial in nature, the CBR observes that it has been largely “insensitive” to interest rate hikes, blunting the CBR’s main tool for combatting inflation (see Figure 4). Consequently, to cool off overall borrowing, the CBR says it has been forced to tighten far more aggressively than would otherwise have been needed.

High borrowing costs are causing financial distress among otherwise healthy companies in the “real” economy, leading the CBR to voice concerns over “the risk of major companies becoming overindebted.” These at-risk companies likely includes Gazprom, which has been borrowing heavily in the domestic markets at 22% and higher to cover losses from the collapse of its core business—European exports.

The CBR has also voiced concern over the condition of major banks, which have been operating under greatly eased regulatory policies since sanctions were stepped up in early 2022. According to the CBR, some banks have taken advantage of eased policy to lend “aggressively” without maintaining sufficient “short term liquidity” and adequate “capital buffers.”

Additionally, bank credit risk has likely been significantly increased by the large amount of state-compelled lending to weak-credit businesses that may struggle to service their loans, especially once defense spending is reduced. This creates the prospect of a systemically destabilizing pool of toxic debt spreading across the corporate credit markets.

In a possible sign of how problematic bank loan books have become, in November 2024, the CBR announced a long-awaited schedule for tightening bank regulatory policy—only to turn around in December and unexpectedly postpone its tightening plans.

Russia’s off-budget defense funding schemes have turned toxic twice before—in 2016-17 and again in 2019-20. Both times, the state had to assume large amounts of bad debt. Given the scale of today’s off-budget credit scheme, the potential bail out could be extremely burdensome for the state—totaling as much as half of Russia’s entire 2024 federal budget. This could constrain state finances for an extended period, including its ability to fund future rearmament—provided, of course, that Russia doesn’t receive substantial sanctions relief.

In short, it is now apparent that Moscow’s heavy reliance on off-budget bank financing to help fund the war is creating the preconditions for a systemic credit crisis. By driving up interest rates, it is creating financial distress among companies in the “real” economy. And by imposing significant amounts of debt on war-related companies that are likely to default over time, it risks overwhelming banks with a wave of toxic debt. Unsurprisingly, since late October, the CBR been publicly calling on the government to curtail its preferential funding scheme. But this would undercut the state’s ability to maintain current levels of war funding without a major increase in official defense budget expenditures.

3) By late 2024, the Kremlin had become aware of the systemic credit risks unleashed by its off-budget defense funding scheme. This has created a dilemma that is likely to weigh on Moscow’s war calculus: the longer it relies on this scheme, the greater the risk a disruptive credit event occurs that undermines its image of financial resilience and weakens its negotiating leverage. Moscow’s emerging financing dilemma offers unexpected negotiating leverage to Ukraine and its allies. There are two key measures that well-informed negotiators can take to exploit Moscow’s growing financial vulnerability.

On October 28th, Vladimir Putin convened a meeting of senior officials, including the head of the CBR, to discuss problems around the “structure and dynamics” of Russia’s “corporate debt portfolio.” Since then, he has publicly shown heightened sensitivity to defense spending levels and the state’s use of preferential lending to achieve “strategic tasks.” Additionally, there continues to be negative news flow around rising levels of financial distress in both the corporate and consumer sectors.

Unlike the slow-burn risk of inflation, credit event risk—such as corporate and bank bailouts—is seismic in nature: it has the potential to materialize suddenly, unpredictably and with significant disruptive force, especially if it becomes contagious. At this point, Moscow is unlikely to be worried that a major credit event risk could destabilize the government. Or even prevent it from maintaining elevated spending on the war. It can probably still fall back on major tax hikes and increases in state borrowing—though clearly prefers not to.

Moscow greater concern is likely Russia’s deteriorating credit environment could unleash events that dispel the widespread misperception—artfully promoted by Moscow—that Russia’s war finances are sustainable and face no significant risks. That misperception provides Moscow with valuable leverage in prospective negotiations. Moscow’s practice of manipulating perceptions around defense spending for political advantage is nothing new; it was widely practiced in Soviet times as part of a broader campaign of reflexive control.

Moscow now faces a dilemma: the longer it puts off a ceasefire, the greater the risk that credit events uncontrollably arise and weaken Moscow’s negotiating leverage.

This is a serious enough concern to factor into Moscow’s ceasefire calculus. Specifically, it could incentivize Moscow in two ways:

i. to prioritize relief around revenue-constraining sanctions as a condition of a ceasefire; this would provide much needed additional resources for restructuring large-scale, toxic corporate war debt while also funding rearmament;

ii. to favor a ceasefire sooner rather than later, to reduce the risk that a credit event weakens its negotiating leverage; if, however, Moscow believes significantly greater sanctions relief could be achieved by prolonging hostilities, it may be prepared to take the risk of doing so.

Ukraine and its allies can exploit Moscow’s funding dilemma by taking two measures:

i. Quietly voice confidence that Western resources can outmatch Russian resources in a war of attrition, backing up that message with a renewed package of funding and arms along with stepped up sanctions enforcement—following up on the January 10, 2025 ratcheting up of energy sanctions. Moscow fully understands it simply cannot prevail against a resolute deployment of Western resources. Which is why it invests so much effort into persuading Western opinion otherwise, in hopes of inducing despair and fatigue that lead to unnecessary concessions. A renewed display of Western resolve will weaken Moscow’s confidence in its ability to secure negotiating advantage through bluff and deception. The prospects of having to match superior Western resources in an extended conflict will only deepen Moscow’s concerns over its newly emerging funding vulnerability. This will pressure it to quietly reconsider its calculus of confrontation, as we have seen it do many times before.

ii. State robustly and categorically that sanctions relief is entirely off the table in any ceasefire negotiations and will only be considered as part of a comprehensive peace settlement—including reparations—that is negotiated and approved by Ukraine. In the face of renewed Western resolve, one thing that could cause Moscow to prolong fighting is if it believed it could gain additional sanctions relief by fighting on. By categorically removing sanctions relief from any ceasefire talks—and persuading Moscow that this is non-negotiable—it will weaken Moscow’s incentive to prolong fighting. It is also tantamount to calling Moscow’s bluff that its finances remain robust and sanctions have been ineffectual. Moreover, maintaining sanctions—with robust enforcement—will also constrain Moscow’s ability to rearm following a ceasefire, while leaving Ukraine and its allies with powerful negotiating leverage in any eventual comprehensive settlement.

Moscow’s funding challenges only increase from here, especially if coalition countries enforce more fully the powerful energy sanction tools at their disposal.Through continued resolve and a clear understanding of Moscow’s vulnerabilities, Ukraine and its allies can realize the full potential of their negotiating leverage, avoid making unnecessary concessions, and reduce the longer-term risks posed by Russian revanchism.

About the author

The author worked for many years as an investment banker at Morgan Stanley and Bank of America Merrill Lynch, where he was a vice chairman. During his banking career, he advised companies and governments around the world and led numerous financings, including Russia’s largest ever corporate transaction. He received an undergraduate degree in Russian studies and a doctorate in Russian and Middle Eastern history from Harvard and a masters in Middle Eastern languages from Oxford, where he was a Rhodes Scholar. Currently, he conducts research on Russia’s energy economy at Harvard’s Davis Center and is writing a history of the Russian oil industry and its impact on civil society. He also is the author of the Substack Navigating Russia.

[The full report, Russia’s Hidden War Debt, is expected to be published in the coming days on Navigating Russia.]

Disclaimer: No Advice

The author of this substack does not provide tax, legal, investment or accounting advice. This report has been prepared for general informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for tax, legal, investment or accounting advice. The author shall not be held liable for any damages arising from information contained in the report.

© Copyright 2025, by Craig Kennedy. All rights reserved.

The claim that $415 billion of corporate debt growth since 2022 is directly tied to war funding is problematic.

Around $250 billion of this increase can be attributed to non-war factors, such as:

- Russian companies acquired $328 billion in foreign-owned assets after sanctions, likely requiring $50–80 billion in borrowing.

- Corporate obligations to non-residents have fallen by $130 billion, necessitating refinancing within Russia.

- Changes in trade terms, such as the loss of advance payments and payment delays, likely added $50 billion in financing needs.

These factors account for much of the debt surge, leaving an estimated $70–100 billion potentially linked to war-related preferential loans.

The suggestion that the banking sector is the primary source of war funding also overlooks critical details:

- Corporate deposits have also risen significantly.

- Banks owe over $200 billion to the extended government (Treasury and Central Bank), creating a more complex picture.

Also, note that investment levels in 2023 were the highest in post-Soviet history. Also, management buyouts of businesses previously owned by expatriates were often financed domestically, further driving corporate borrowing.

References like "Central Bank of Russia" are not much informative; one would expect references to specific tables and publications, better yet direct internet links, because everything the CBR publishes is available online.

For instance, here is the regular release:

Non-financial sector and Households debt, extended

https://www.cbr.ru/eng/statistics/macro_itm/dkfs/ext_dep_indicator

Graphs do not seem to demonstrate anything exceptionally dramatic on the non-financial debt front.

As for the supposed riddle of the continuing expansion of business debt after the discontinuation of the subsidized mortgage program, it most likely reflects the legal mechanics of the urban residential construction sector in Russia. Specifically, mortgages extended to households are held in escrow accounts, and only after the proposed development project (almost invariably condo apartments) is fully subscribed to, developers borrow against these escrow accounts (at the rates that more or less match the underlying mortgages rates), and start actual construction activities. This mechanism creates a lag between the approval of mortgages to households and the approval of lending to developers.