April 2022

Robust cash flows from Russian oil exports are blunting the impact of sanctions. Calls for a full embargo, however, face political resistance over fears that a supply shock could trigger a recession and undermine Western unity. This paper makes recommendations on how to enhance the economic impact of oil sanctions while mitigating their harmful effects on the world economy. They include a proposal to augment a full oil embargo with a smart embargo option. This option could eliminate Russian tax revenues on oil exports, while also averting a supply shock and providing funds for Ukraine reparations at Russia’s expense. The proposal takes advantage of vulnerabilities in the Russian oil industry that have been largely overlooked in the current sanctions debate.

Executive Summary

The continued flow of oil export revenues into Russia is blunting the impact of Western sanctions. At today’s prices, Kremlin tax receipts on export oil alone will cover 70% of Russia’s Federal Budget for 2022. The most obvious remedy to this problem—a full embargo on Russian oil exports—continues to face resistance from some European policy makers. They fear an oil supply shock would trigger a recession that, in turn, could undermine the Western unity needed to counter Russian aggression.

This paper makes recommendations on how to structure an oil embargo strategy in a way that enhances its economic impact. These recommendations include a proposal for a smart embargo option that could stem the flow of Russian tax revenues from oil exports while also averting a politically risky global supply shock. What is more, it would also fund Ukraine reparations at Russia’s expense.

These recommendations take advantage of certain structural vulnerabilities in the Russia oil industry—largely overlooked in the current sanctions debate—that severely limit Russia’s ability to redirect or reduce the 6 million barrels a day it exports to the West—over half its total output. Russia itself consumes around a quarter of its own output. The balance, however, must be exported (Figure 1). China buys less than 20% of these exports, while the West normally absorbs over 70%. These Western imports represent more than half Russia’s entire oil output.

Figure 1

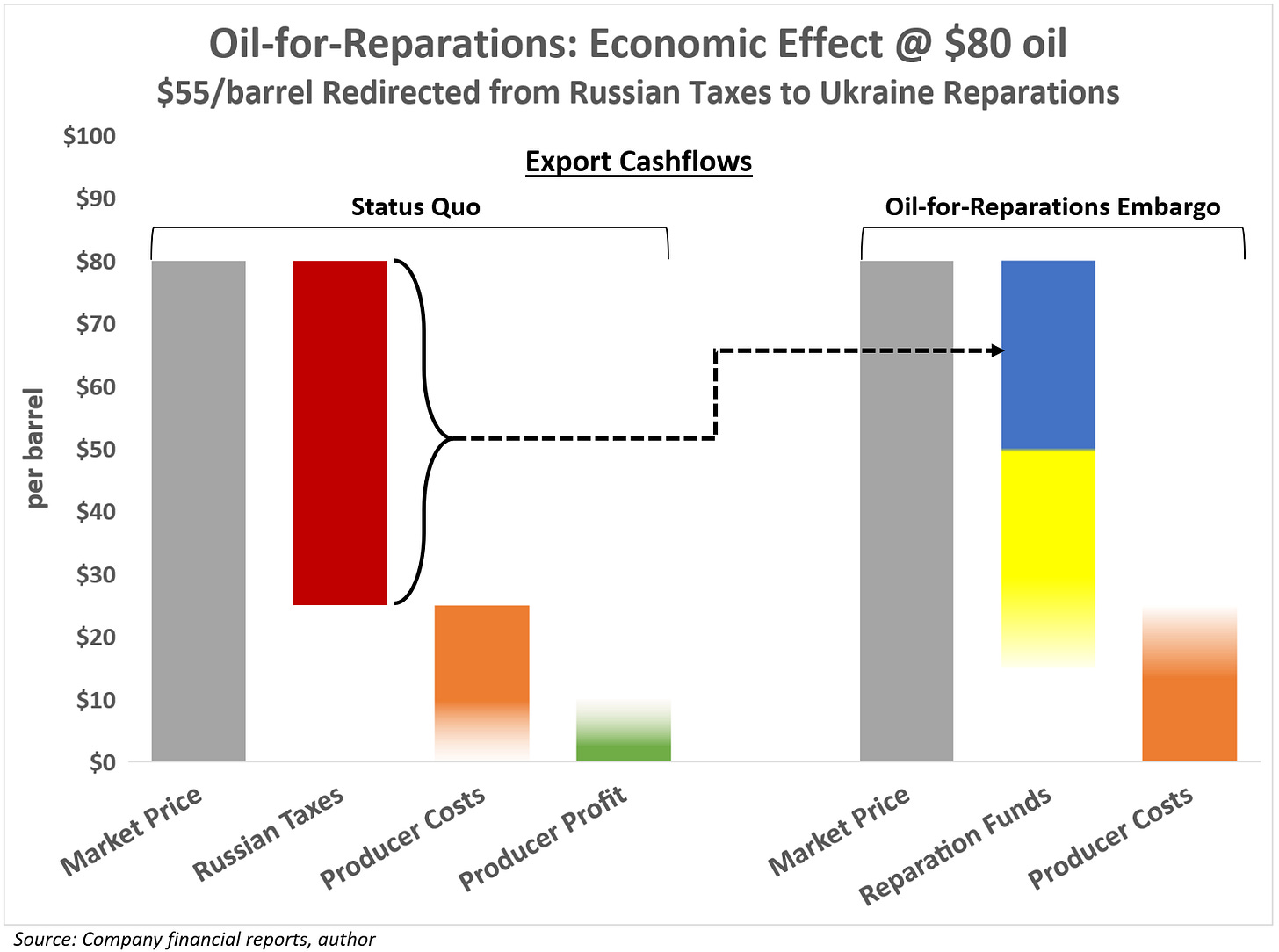

In the event of an embargo, Russia has threatened to redirect its Western export volumes elsewhere. But these “export substitution” threats are hollow—the volumes are far too large to redirect. Russia’s Western export volumes are far too large for China and India to absorb without abandoning their practice of diversifying supplier risk and relying on Russia for nearly half their oil imports. Significant infrastructure and logistical constraints also limit Russia’s ability divert oil East. And if the West imposes secondary sanctions on any enablers of Russia’s seaborne oil trade, Russia would struggle to redirect more than a fraction of its Western exports.

If export substitution is not possible, Russia’s only real option under a Western embargo would be to leave the banned oil in the ground. This would mean “shutting in” more than half its current output. That’s an immense quantity of oil, equal to roughly 6% of global output. Such a scenario would be severely damaging to Moscow for several reasons, some self-evident others less so. Most obvious would be the loss of vital export revenues. While these might be offset by higher prices for Russia’s few remaining exports, the offset would likely be partial and short-term only.

Less evident than revenue loss, however, is the severe damage an extended, large-scale shut in would do to Russia’s upstream production capacity. It could render tens of thousands of marginal wells uneconomic and compromise complex pressure management systems at the field level. This risk is well appreciated by Russian reservoir engineers, but less evident to Western policy makers. Additionally, this could also deeply undermine political support for the Putin regime in Russia’s oil producing regions.

A major shut-in would also erode Russia’s standing in OPEC+ and put Russia’s export market share at risk. Finally, it would erode the mainstay of Russia’s centralized, rent-gathering economy that helps enable an authoritarian form of government.

If export substitution is a chimera and a large-scale shut-in potentially catastrophic, Russia is far more dependent on the West to absorb its oil than many Western policy makers may realize. This dependency gives the West significant bargaining leverage—but only if it acts collectively. Properly exploited, it can be used to design smart oil sanctions that achieve Western objectives while minimizing self-harm.

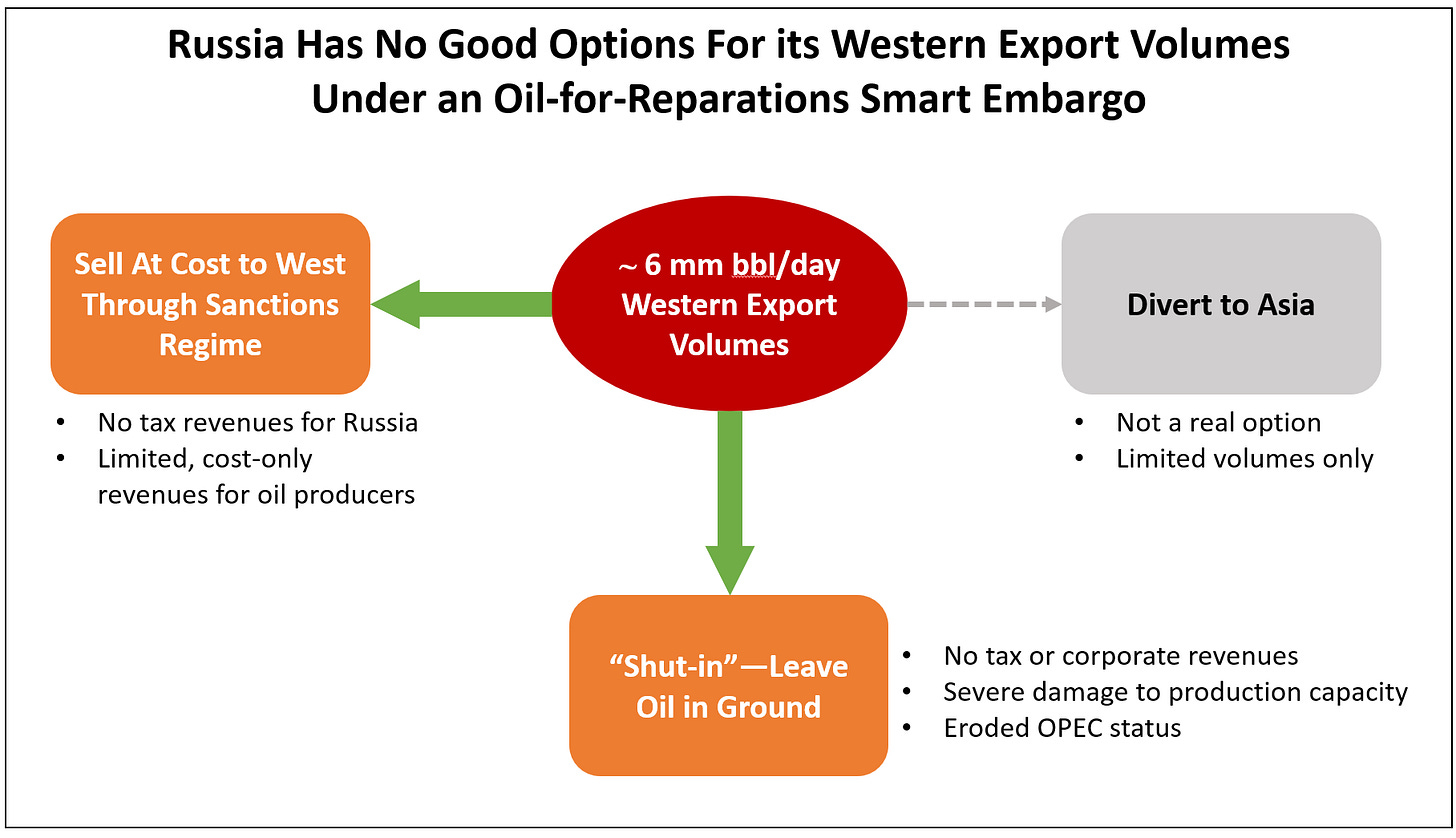

There are different ways to exploit this leverage, such as imposing a special export tax. This paper proposes augmenting a standard embargo with an “oil-for-reparations” smart embargo option that allows for controlled export sales while severely restricting the proceeds remitted to Russia.

Under this framework, the Western governments would agree to proceed with a full embargo of Russian oil exports (Figure 2). But the embargo would include a special provision that would allow Russian producers to keep exporting oil, provided all proceeds are channeled through a special Payment Authority established by the West. The Payment Authority would remit a portion of the sales proceeds back to the Russian producer—enough to cover average production costs excluding all Russian taxes, but nothing more.

Figure 2

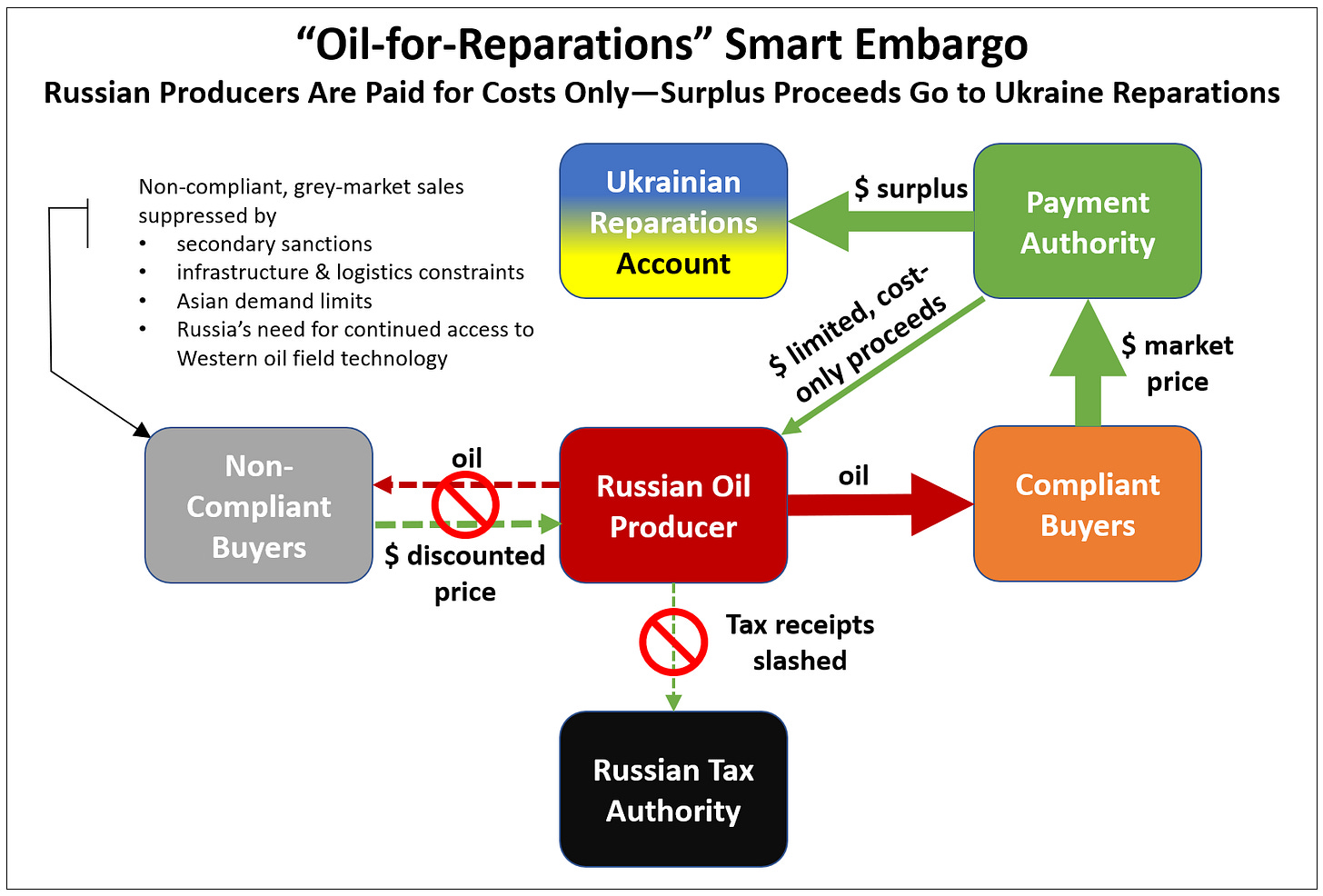

Based on average Russian costs, this would be around $20 -$25 a barrel or roughly a quarter of today’s oil price. The remaining surplus—what would normally flow to the Kremlin as taxes—goes instead to Ukraine for reparations (Figure 3). At today’s prices that would be around $55 a barrel, equal to around a half a billion dollars a day. Accordingly, this framework could be called the “Oil-for-Reparations (OFR) Sanctions.”

Figure 3

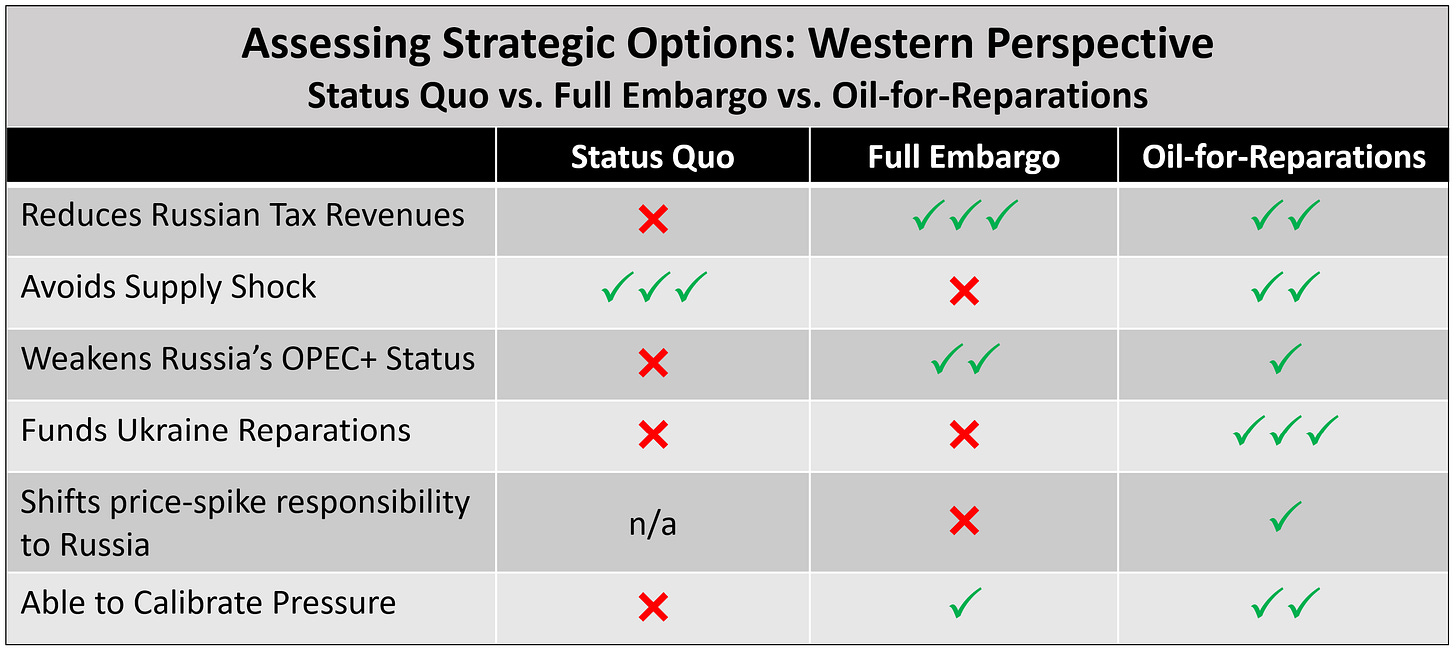

This Oil-for-Reparations framework has several advantages: 1) it funds Ukrainian reparations at Russia’s expense, 2) it prevents an oil price shock and 3) it slashes Russian oil tax revenues, with severe consequences for the Russian budget. Its chief drawbacks are 1) some corporate oil export revenues continue to flow back into Russia and 2) it cannot be imposed unilaterally; Russian producers must agree to sell.

This last point—the need for compliant sales by Russia—is a significant uncertainty. As part of the framework, the West must impose secondary sanctions on any non-compliant export sales outside of the sanctions regime. This would make it all the more difficult for Russia to redirect a significant portion of these volumes elsewhere. Russia’s Western volumes would, in effect, become “captive oil.”

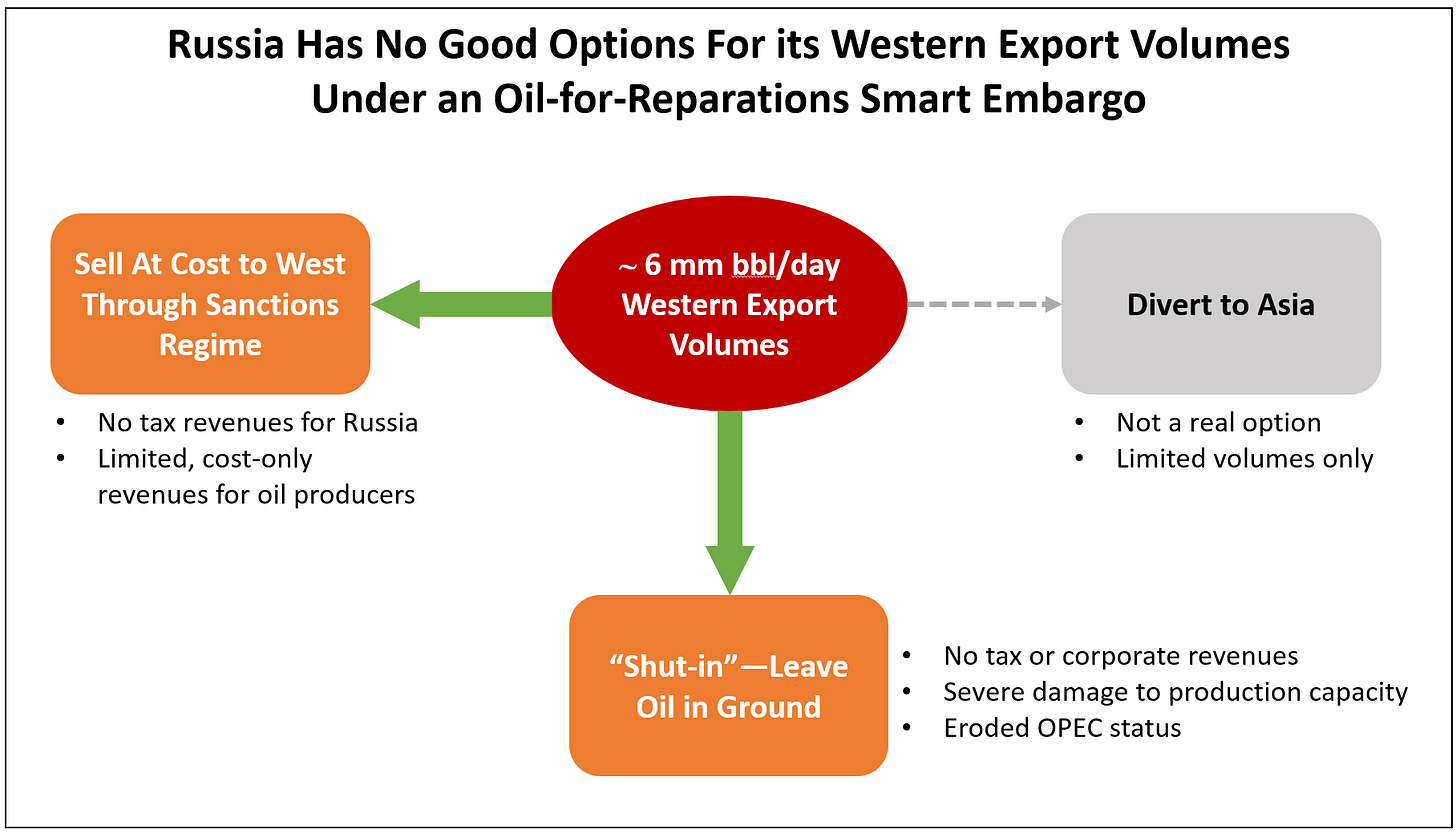

That would present Russia with a stark choice: either agree to export under the sanctions regime, or voluntarily elect to shut in most export oil (Figure 4). While agreeing to sell is clearly in Russia’s economic interest, it’s entirely likely the Kremlin would opt instead—at least initially—to start shutting-in in hopes of roiling global markets and breaking Western resolve. And one cannot assume that Putin will be fully briefed on the catastrophic impact such a shut-in could have on Russia’s oil sector.

Figure 4

Even if Russian opts for a shut-in, there are still significant advantages to including a smart embargo option. For one thing, Russia might decide, instead, to participate—if not immediately, then at some later point. Additionally, having this option goes some way to shifting responsibility for the shut-in—and the resulting supply shock—away from the West and onto Russia. Politically, that shifting of responsibility is valuable. The price spike following a full shut in will be painful for oil consumers everywhere. OPEC, likewise, will not welcome loss of control over prices. The smart embargo strategy shows a good-faith effort by the West to prevent a supply shock. If a supply shock does occur, Russia will have to share the blame, including from erstwhile ally China.

The West should also prepare an expansion of current oil field services sanctions. At present, these are very limited and have little impact on current production. Russia is growing increasingly dependent on Western oil field equipment, services and technology to maintain production levels. The West should prepare to expand these sanctions to ban all Western oil field services in Russia, especially If Russia opts for a self-imposed shut-in.

* * *

Table of Contents

Part 1 is an overview of Russia’s oil production and exports. It shows how Russia exports three quarters of its oil output and how 70% of those outputs flow to the West.

Part 2 discusses Russia’s highly progressive oil tax regime on exported oil, in which 80 cents of every incremental dollar is captured by the state as oil prices rise above $25 dollars a barrel.

Part 3 shows that Russia’s threats to divert Western export volumes elsewhere are hollow. Faced with constrained demand, infrastructure and shipping logistics along with secondary sanctions risk, Russia would struggle to divert more than a small fraction to Asia.

Part 4 shows that Russia’s only actual option to selling West is shutting-in production, but that this is an unattractive option for Moscow, since it would deny it vital tax revenues and severely damage its upstream oil production capacity.

Part 5 makes recommendations on how to exploit Russia’s high dependency on Western oil markets. They include augmenting a simple embargo with a restricted-proceeds option that would slash Russia’s oil tax receipts, while averting an oil supply shock and providing funds for Ukraine reparations at Russia’s expense.

An Appendix addresses a technical issue of how to maintain market pricing for Russian export sales in the Oil-for-Reparations framework.

Part 1: Russian Oil Export Volumes—Heavily Skewed to the West

Russia exports three quarters of its production...

Russia typically exports over 8 million barrels a day of oil—that’s about 75% of its total current output of nearly 11 million barrels a day (Figure 5). This makes it one of the world’s largest exporters, accounting for one in every eight barrels traded in the international markets. About 60% of the oil Russia exports is in the form of crude, but another 40% goes out as refined products, such as diesel, fuel oil and naphtha, a fact often overlooked in media reports on Russian exports.

Figure 5

...and relies on the West to buy 70% of its exports—equal to more than half of total Russian oil output.

Russia relies on heavily on the West to buy most of its oil exports, more than 70 percent (Figure 6). This means Russia sells more than half the oil it produces to the West, either as crude or in the form of refined products. China, though the single largest buyer, accounts for less than 20% of Russia’s export sales or around 15% of Russia’s total production.

Figure 6

Part 2: Russia’s Aggressive Oil Tax Regime—the Mainstay of State Finances

As oil prices rise above $25 a barrel, 80% of each incremental dollar goes to the State

Taxation of export oil has long been the mainstay the Putin regime. This is possible because Russian oil is cheap to produce and the Russian government taxes oil aggressively. Industry costs have been creeping up in recent years as declining, low-cost fields are replaced by more expensive new ones. Nonetheless, Russia’s full-cycle costs remain mostly in the range of $20 - $25 (these are the costs to find, develop, produce and move a barrel of oil).

Russian oil taxes are closely tied to the oil price. Taxation begins as prices rise above $15 a barrel. As prices rise above $25, the marginal tax rate rises to near 80%. This means for every incremental dollar in the oil price above $25, the state takes 80 cents. At today’s Urals blend price of $80, for example, the Kremlin is collecting $55 for every barrel exported (Figure 7). The remaining $25 goes to the producer to cover costs. Some tax relief is available for certain projects, such as greenfield developments.

Figure 7

Today, oil exports alone generate nearly $500 million in tax receipts every day—enough to fund 70% of the 2022 Federal Budget

Russia’s tax haul on oil exports is immense, which makes it the largest single source of government revenues. Currently, oil exports alone are generating nearly a half billion dollars a day in tax receipts. To put that in context, that’s enough to fund 70% of Russia’s entire federal budget expenditures for 2022 (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Part 3: The illusion of export substitution: why Russia would not be able to redirect a significant portion of its Western export volumes East, especially if secondary sanctions are imposed

Rising calls in the West to ban Russian oil are threatening Moscow’s most important source of tax revenue. In response, Moscow has threatened to divert Western export volumes elsewhere. Media stories follow highlighting stepped up sales to China and India. Concerns arise about export substitution to Asia. But a close examination shows that the threat of Asian export substitution is a paper tiger.

There are three major reasons for this, all of which arise from the immense scale of Russia’s Western export volumes.

1. These volumes are far too large for Chinese and India to absorb without abandoning their practice of diversifying supplier risk and relying on Russia for nearly half their oil imports.

2. Russia would quickly run up against significant infrastructure and logistical constraints as it tried to divert its Western exports East.

3. If the West imposes secondary sanctions on Russian exports, the chilling effect on critical intermediaries for the long-haul seaborne oil trade would make it difficult for Russia to redirect more than a fraction of its Western volumes.

Let’s cover reason each in turn.

1) Asian Demand Limits

China and India together would not be able to absorb Russia’s Western exports without taking on unacceptable concentration risk—the volumes are simply too great...

Asia is home to the first and third largest oil importers in the world, China and India. Large as they are, however, the collective West is far larger—importing double China and India combined (Figure 9). And when it comes to imports of Russian oil, the West’s relative volumes are even greater—four times as much.

Figure 9

Scale matters when the question of Asian export substitution comes up. At present, Russian supplies only 9% of China and India’s combined oil imports. Were they to try to absorb the volumes Russia normally sells to the West, their dependency on Russia for imported oil would jump to nearly 45%.

Taken individually, the story for each country is much the same.

...Russia’s share in Chinese oil imports would jump to 47%...

For China, Russia is already one of its top two suppliers, providing around 14% of China’s imported oil (Figure 10). Were China to absorb Russia’s western export volumes on a pro-rata basis with India, Russia’s share in China’s imports would grow to 47%. To make room for all this new Russian oil, China would need to cut back other suppliers by 39%.

Figure 10

...while for India, it would skyrocket to 40%.

The story with India would be much the same (Figure 11). The only real difference being that Russia’s current share in India’s import portfolio is very low—around 1.5%. With no direct pipeline connection, all Russian oil to India must go by sea. Russia’s low share in Indian imports illustrates how uncompetitive it is to ship Russian oil from the Black Sea or Baltic to India. But if India were to absorb Russia’s Western exports pro rata with China, Russia’s share in Indian exports would rise to 40%. And it would also have to cut back it other suppliers by 39%.

Figure 11

It is hard to imagine either country voluntarily accepting such a high level of concentration risk around a single supplier. Both are heavily reliant on oil imports and manage oil import risk by broadly diversifying suppliers. For China, this is a formal national security policy. Absorbing that much Russian oil would mean abandoning efforts to manage import risk. Absorbing even half of Russia’s Western export volumes would still create very high levels of Russia dependency, especially China, who would be relying on Russia for a third of its oil imports.

Other factors would also limit incremental demand, such as existing OPEC supply relationships...

Beyond concentration risk, there are other factors that would limit China and India’s appetite for additional long-term Russian supply agreements. To begin with, it would mean cutting back other suppliers by 39% for both China and India under the scenarios above. Many of these suppliers are OPEC members with whom they have long-standing supply relationships they may be reluctant to upend.

... and concerns over numerous Russia-specific risks

And then there are numerous Russia-specific risks. Russia is already saddled with Western sanctions, with more likely to come. Russia also has a track record of weaponizing energy exports. Russia faces severe infrastructure and logistical constraints on its ability to reliably transport large incremental volumes to Asia (see below). And if the West imposes secondary sanctions under the OFR Program, these constraints become even more severe.

At distressed prices, China and India will likely be opportunistic buyers, but cannot be counted on to absorb large portions of Western volumes on an on-going basis

To be sure, China and India will pick up incremental supplies from Russia on an opportunistic basis, if the price is right and the risks manageable. But it’s hard to imagine them being willing to absorb more than a fraction of normal Western export volumes on an on-going basis.

2) Russian Infrastructure & Logistic Constraints

Russia’s export infrastructure is heavily skewed Westward, creating major logistical constraints and vulnerabilities for redirecting Western volumes to Asia

Russia’s river of oil flows mostly West. This has been the case since the late 1870s, when Russian oil first reached Western European markets. Today, exports flow West through an immense infrastructure of pipelines, ports, refineries, and rail links (Figure 12). These took decades to build and cost tens of billions of dollars. These exports are supported by a dense commercial network of bankers, traders, refiners, insurance brokers and shipping companies, many with deep and long-standing expertise in the Russian oil trade.

Figure 12

Most Russian exports come from fields in West Siberia and the Volga-Urals basin and over 80% of them are destined for Europe. Some volumes travel via the Druzhba pipeline (opened in 1964) directly to European refineries. Others are shipped by tanker out of the Black Sea and the Baltic on short runs to Europe. En route out of Russia, 45% of Western exports are run through one of the two dozen refineries in Western Russia.

Russia’s much smaller Eastern export infrastructure is already running near capacity

Russia’s Eastern export infrastructure is young and modest by comparison to its Western counterpart. The first long-haul export pipeline from West Siberia to China reached full capacity only in 2019. At 4,188 kilometers, it is the world’s longest oil pipeline and took over a dozen years to complete at a cost of some $25 billion. It can deliver 600,000 barrels a day directly to China’s Daqing refinery and another 1 million barrels a day to Russia’s Pacific oil terminal at Kozmino. But this totals only about a fifth of Russia’s Western export capacity.

Additionally, two much smaller terminals send exports out of Sakhalin Island. Russia’s eastern export infrastructure is already running near capacity. It would not be able to carry significant portions of Western volumes to new, Asian markets. Significantly expanding this capacity would take years and billions of dollars.

The only way to redirect large Western volumes to Asia is by oil tankers out of the Black Sea and the Baltic...

If Russia wanted to divert significant Western export volumes to Asia, it would have to move them by tanker from terminals in the Black Sea and the Baltic. Rerouting all those Western volumes would put well over a million barrels a day of additional load on Russia’s main sea terminals, which could pose a bottleneck.

...but this would strain global capacity, requiring a quarter of the world’s super tanker fleet

But by far the greater challenge would be finding enough oil tankers to carry all that oil to Asia. Currently, Russia’s seaborne exports make short trips to Mediterranean and Northern European ports. To shift those volumes to Asia would demand larger vessels that would need to spend 10 times as many days in transit, with a round trip taking the better part of three months.

Moving that much oil over that much distance would require a dedicated fleet of some 200 VLCCs (very large crude carriers) working day in and day out. That’s equal to a quarter of the entire global VLCC fleet. And half the time, those vessels would be returning empty back to Russia. It’s doubtful Russia would be able to charter this much capacity at any economic price. Russia does have its own modest tanker fleet, but it could barely manage a tenth of the volumes involved.

3) Secondary Sanction Risk

Russia’s greatest barrier to export substitution would be secondary sanction risk, which would likely shut down most non-compliant seaborne trade.

In the end, this analysis of global tanker capacity is somewhat academic, since most of these tankers could probably never be chartered in the first place. The reason—the secondary sanctions risk

As noted above, almost any additional volumes Russia sells to Asian buyers would need to go by sea. But seaborne oil is much more vulnerable to sanction risk than pipeline oil. This is especially true with Russian oil. It would have to rely on an immense fleet setting sail through heavily monitored waterways like the Bosphorus and the Danish Straits. From there, they would have to sail 40 plus days to their destination, while carrying cargos worth $150 million. A large-scale operation like this involves a host of intermediaries: banks to provide letters of credit, cargo financing and payment transactions; charter shipping companies; marine insurers and commodity traders (Figure 13).

Figure 13

Were the West to impose secondary sanctions on seaborne sales to Asia, it would have a deeply chilling effect on this trade. Few of the needed intermediaries would be prepared to risk sanctions. Russia might be largely reduced to relying on its own small fleet. The only other volumes likely to evade sanctions are the 10% of exports already going to China via overland pipelines. In short, if the West imposed secondary sanctions on non-compliant sales to Asia, Russia would struggle to divert even a small portion of its Western volumes East.

Part 4: An extended, large-scale shut-in of Russia’s oil output would severely damage a large part of its upstream production capacity.

Russia’s only real option to selling half its oil to the West is to leave it in the ground...

If export substitution is not possible, Russia’s only option under a Western embargo would be to leave the embargoed oil in the ground. This would mean “shutting in” more than half its current output, equal to roughly 6% of global oil production.

...but this is a highly unattractive option for Moscow.

Such a scenario would be highly unattractive to Moscow for several reasons, both obvious and less so. Most obvious would be the loss of vital export revenues. These would include not only the state’s tax revenues on exported oil—also lost under OFR sanctions—but also cost-only corporate proceeds allowed under the OFR program. As mentioned above, Russia’s Western exports alone are generating around $500 million per day in tax revenues—enough to cover 70% of the 2022 Federal Budget. While this loss might be offset by higher prices for Russia’s few remaining exports, the offset would likely be partial and short-term only. In time, supply and demand would respond to bring prices down.

In addition to lost revenues, a large-scale, long-term shut-in would cause severe damage to Russia’s upstream production capacity

Less evident than revenue loss, however, is the severe damage an extended, large-scale shut in would do to Russia’s upstream production capacity. Shutting in Russia’s Western export volumes would entail reducing total Russian oil output by more than half, or around 6 million barrels a day. And it would entail severe consequences for Russia’s upstream production capacity.

The reason for this is that Russia’s upstream oil industry lacks flexibility for large-scale “swing” capacity. Swing capacity is the ability to nimbly ramp up or throttle back oil production without causing material damage to production capacity. This is often accomplished by reducing the flow rates out of highly productive wells, rather than idling those wells altogether, which can cause complications.

The Russian upstream has structural limitations on its swing capacity

The world’s leading swing producer is Saudi Arabia. Thanks to its phenomenal petroleum geology and a state-of-the-art infrastructure, an average Saudi well produces thousands of barrels a day. Most of its production is highly concentrated geographically and not far from major coastal export terminals. This gives Saudi Arabia effective swing capacity of several million barrels a day over a short time period.

Many Russian oil wells barely break even …

Russia’s swing capacity, by contrast, is much more limited. This constraint arises from the sluggish and sprawling nature of Russia’s upstream oil complex. It consists of some 160,000 wells penetrating 2,600 fields spread across nine time zones. Many are located in some of the most remote and inhospitable terrain on the planet, thousands of kilometers from the sea.

A defining feature of most Russian oil wells is modest profitability and low flow rates, with most wells producing just 50-70 barrels per day. And when you factor in high transportation costs and heavy taxes, many barely turn a profit, even at high oil prices.

…and require complex pressure maintenance programs

Many of these wells remain profitable only thanks to complex field operations that help maintain pressure deep underground in the oil reservoirs. This pressure helps push oil into the well bores where it can be lifted by electric pumps. In Russia, reservoir pressure is often maintained by an enhanced recovery method called “waterflooding.” It’s a standard industry practice that involves injecting vast amounts of water into the reservoir through injection wells to help maintain formation pressure and “sweep” oil deposits towards producing wells.

Getting the sweep patterns right is not easy and often involves the use of sophisticated reservoir simulation models. If water is injected in the wrong place or the pressure is too high, the producing wells will end up lifting far more water than oil, killing off profitability.

A large-scale shut-in would require idling tens of thousands of marginal wells...

Under a large-scale shut-in, Russia would need to idle tens of thousands of marginal wells. This would have dire consequences, especially the shut-in lasted not weeks, but years. Without the continuous flow of fluids, reservoir pressure can be hard to monitor and manage. Pressure can collapse or dreaded water breakthroughs occur.

When Russian wells fall idle, other bad things can happen, too. For example, waxy paraffins can build up that clog pores through which the oil flows. Surface and downhole equipment can fall into disrepair. And there are numerous other cascading technical risks.

… rendering many uneconomic to reopen and severely damaging Russia’s production capacity.

When it comes time to bring these idle wells back on stream, they may need “workovers” to get them flowing again at profitable levels. This is a costly, labor-intensive, well-by-well intervention carried out by specialist crews. And if problems such as reservoir pressure can’t be fully rectified, many formerly marginal wells may never be restored to profit. They’ll need to be abandoned, and new ones drilled requiring far more time, technology and expense. Entire fields could be rendered uneconomic.

The closest analogue comes from the early 1990s, when Russia’s oil production collapsed by five million barrels a day from underinvestment. It took over a decade and large amounts of Western capital and technology for Russia’s lost production capacity to be restored.

A self-imposed shut-in would also weaken Russia’s standing with OPEC, jeopardize its export market share, weaken political support from Russia’s oil regions and erode a central pillar of Putin’s autocratic rule.

Apart from losing vital revenues and damaging its oil production capacity, there are other reasons Moscow would want to avoid a self-imposed, large-scale, long-term shut-in.

It would erode Russia’s standing as strategic partner for OPEC. Moscow could no longer be counted on to coordinate production quotas to help manage the oil price. And while OPEC might welcome the windfall profits from an oil price spike, it does not generally like losing control over market dynamics.

It would also jeopardize Russia’s long-standing position in its most important export market—Europe—as other suppliers stepped in to establish new relationships and high prices helped fund development of alternative energy supplies.

It would cause economic hardship in Russia’s oil regions and force local oil workers to implement measures they know would damage future prospects for regional recovery. This would likely weaken support for Putin’s in important regions.

Finally, maintaining tight control over the redistribution of Russia’s oil rents has been a central pillar of Putin’s autocratic rule. A shut-in would erode some of the power he exercises as Russia’s redistributor of rents.

Part 5: Recommendations: The Oil-for-Reparations Program—Redirecting Russian Oil Taxes to Fund Ukraine Reparations

Russia has no good options for its large Western export volumes apart from selling them to the West

Russia has few good options for managing the 70% of its export oil it currently sells to the West. It lacks an ability to redirect them en masse to Asia, especially if faced with Western sanctions. And leaving those volumes in the ground, unproduced, would have severely damaging consequences.

This dependency gives a united West significant collective bargaining leverage...

This inflexibility of the Russian oil industry makes it highly dependent on the West. And this dependency gives the West significant bargaining leverage—if it acts collectively. Properly exploited, it can be used to design a smart oil embargo that achieves Western objectives while minimizing self-harm.

...than can be used to enhance sanctions and reduce the risk of self-harm

There are different ways to exploit this leverage, such as imposing a special export tax. This paper proposes augmenting a standard embargo with a smart embargo option that would allow for controlled export sales while severely restricting the proceeds remitted to Russia.

How a smart embargo option would work. Governments must be prepared to impose an outright embargo...

Under this smart embargo framework, Western governments would need to agree that they are prepared to proceed with an outright embargo of Russian oil exports. The smart embargo option requires Russian producers to opt in, and there is no certainty they will. But it is conceivable they would, at least in time, since their only other option—a self-imposed shut-in—is highly unattractive, as discussed above.

...that includes a “smart” option permitting Russian exports through a Western-controlled payment regime that remits “cost-only” proceeds to Russian producers while directing surplus proceeds to Ukraine reparations—an “oil-for-reparations” (OFR) program.

The standard embargo would include a smart embargo option that would allow Russian producers to keep exporting oil, but only within the framework of a Western controlled payment regime that severely restricts their proceeds and redirects surplus proceeds into a Ukraine reparations fund (Figure 14).

Figure 14

The structure would work as follows:

The EU would establish a multilateral Payment Authority.

Any international buyer that wished to purchase crude or refined products from a Russian exporter would be allowed to do so, provided they (a) channelled all proceeds through the Payment Authority and (b) conducted the transaction at a fair market price. Accepting these conditions makes them a “compliant” buyer.

Russian exporters would also need to implicitly accept these sales conditions.

the Payment Authority remits a portion of the proceeds back to the Russian seller that is sufficient only to cover average Russian producer costs excluding any Russian taxes. The Payment Authority would publish a schedule of “cost-only” proceeds for Russian export crude and refined products.

the remainder of the proceeds (the “surplus”) is deposited by the Payment Authority into a Ukraine reparations fund.

This smart sanctions option would be known as the “Oil-for-Reparations (OFR) Program.”

To suppress grey-market dealing in contravention of the embargo and encourage Russian participation, the West would take these additional measures:

The embargo would apply to all Russian oil exports worldwide.

Any “non-compliant” international buyer—one that purchases Russian oil outside of the OFR program—would be subject to secondary sanctions. (Russia can ship only around 12% of its oil exports directly overland to Asia—any further volumes must go by sea making them far more vulnerable to secondary sanctions).

The same holds for any intermediaries, such as banks, oil tanker chartering companies, marine insurers, and commodities traders, who enable non-compliant sales.

if Russia opts to shut-in its oil rather than sell into the OFR regime, the current, very narrow sanctions on Western oil field services, equipment and technologies would be expanded to cover all such sales to Russia.

Under the Oil-for-Reparations program, 75% of export sales proceeds—around $500 million a day—could go to Ukrainian reparations at current oil prices

Under the OFR program, the proceeds received by Russian producers would only be enough to cover average production costs excluding all taxes. Based on average Russian costs, the allowed “cost-only” proceeds would be around $20 -$25 a barrel or roughly a quarter of today’s oil price (Figure 15). The remaining surplus—what would normally flow to the Kremlin as taxes—goes instead to Ukraine for reparations. At today’s prices that would be around $60 a barrel, equal to around a half a billion dollars a day (assuming 85% of normal export volumes are sold to compliant buyers).

Figure 15

The oil-for-reparations framework has both advantages and disadvantages compared to a standard embargo

This oil-for-reparations framework has several advantages: 1) it funds Ukrainian reparations at Russia’s expense, 2) it prevents an oil price shock and 3) it slashes Russian oil tax revenues, with severe consequences for the Russian budget. Its chief drawbacks are 1) some corporate oil export revenues continue to flow back into Russia and 2) it cannot be imposed unilaterally—Russian producers must agree to sell (Figure 16).

This last point—the need for compliant sales by Russia—is a significant uncertainty. As part of the framework, the West would impose secondary sanctions on any non-compliant export sales outside of the sanctions regime.

Figure 16

Russia would face a stark choice: compliance or defiance? Initially at least, Russia might well choose defiance and counter-sanctions in hopes of fracturing Western unity

That would present Russia with a stark choice: either agree to export under the OFR sanctions regime, or voluntarily opt to shut in most export oil (Figure 16). While selling is clearly in Russia’s economic interest, it’s likely Russia would opt instead—at least initially—to shut in production in hopes of roiling global markets and breaking Western resolve. The Kremlin could also pursue counter-sanctions of its own, perhaps involving gas exports to Europe.

Figure 17

Even if a Russian self-imposed shut-in is likely, there are still significant advantage to including a smart embargo option in the West’s oil embargo strategy. For one thing, Russia might actually opt to sell into it. This might not happen immediately, but could happen in time, once the Kremlin determined Western unity was firm.

We should also assume that Putin’s advisors will initially downplay the severe consequences of a large-scale shut-in, secondary sanctions on and a full embargo on Western oil field technologies. But once the Kremlin leadership becomes fully aware of the risks, it may also decide to opt in to the OFR regime.

But even if Russia choses to shut-in, offering the oil-for-reparations option still benefits the West

But even if Russia doesn’t sell but stays shut-in, there is advantage to the West in offering the restricted proceeds option: it would shift the responsibility for shutting in away from the West and onto Russia. Politically, that shift is valuable. The price spike following a full shut in will be painful for oil consumers everywhere—including China and India. OPEC, likewise, will not welcome its loss of control over prices. The smart embargo strategy shows a good-faith effort by the West to prevent a supply shock—one which Russia defiantly rejected. And because of its wilful rejection, Russia will have to share the blame.

Additionally, the West should be prepared to expand the very narrow oil field service sanctions currently in place to cover all Russian upstream projects

Western oil field services and technology are critically important to the Russian oil industry and will become only more so as Russia moves to more technically challenging fields. Current sanctions prohibit only a very limited range of projects (arctic offshore, deep water, and shale) and have almost no impact on Russia’s near-term production. The leading oil field service companies appear intent to continue with their pre-existing business in Russia. If Russia opts to shut-in production, the West should expand existing sanctions to prohibit all Western oil field services in Russia.

Summary conclusions and recommendations

Certain structural vulnerabilities in the Russia oil industry severely limit its ability to redirect or reduce the 6 million barrels a day it exports to the West.

Consequently, Russia is highly dependent on Western markets to absorb half its total oil production.

This dependency provides the West greater potential leverage than some policy makers may realize—provided Western countries act collectively, not piecemeal.

This leverage can only be effectively exploited by Western governments acting closely in concert.

Any Western oil embargo should include:

a “smart” oil-for-reparations option that permits Russia to export oil provided that all proceeds are channeled through a Western payment authority that remits limited proceeds back to Russia (only enough for costs, excluding taxes) and assigns surplus proceeds to Ukraine reparations.

secondary sanctions on any Russian oil export worldwide that attempt to circumvent the sanctions regime; these would apply to buyers, sellers and any enabling parties.

expansion of current oil field service sanctions to cover all Russian upstream projects if Russia does not opt into the Oil-for-Reparations sales regime.

Appendix: A technical note on how to maintain market pricing for Russian export sales under the Oil-for-Reparations framework.

Under the OFR program, it would be important to ensure that buyers of Russian oil exports pay full market prices. Since the Russian sellers receive only a portion of the proceeds—enough to cover costs only—they are not incentivized to push buyers to pay a full market price for their exports. If they sell at deep discounts to the market, this reduces the surplus used to fund Ukraine reparations.

There are several ways to avoid such off-market, discounted sales. One is to authorize the Payment Authority to act as the sole marketing agent for all Russian export crude. The Payment Authority would conduct competitive tenders to insure at-market pricing. This will, however, require the Payment Authority to have extensive market expertise. Another possible solution would be to disallow any contract prices below a certain discount to a benchmark crude, like Brent. Maximum discounts could be based on normalized historical averages. A third possible solution could be to incentivize the Russian seller to maximize pricing by allowing them to share in a small percentage of the margin above the cost-only regulated proceeds.

In such a large sanctions program, some amount of leakage, through non-compliant grey-market sales and bad-faith contracts, is almost inevitable. But the sanctions regime doesn’t need to be completely water-tight and fraud-proof to be effective. It just needs to be robust enough to dramatically cut oil tax receipts to the Kremlin and transfer those forfeited tax revenues to pay for rebuilding Ukraine.